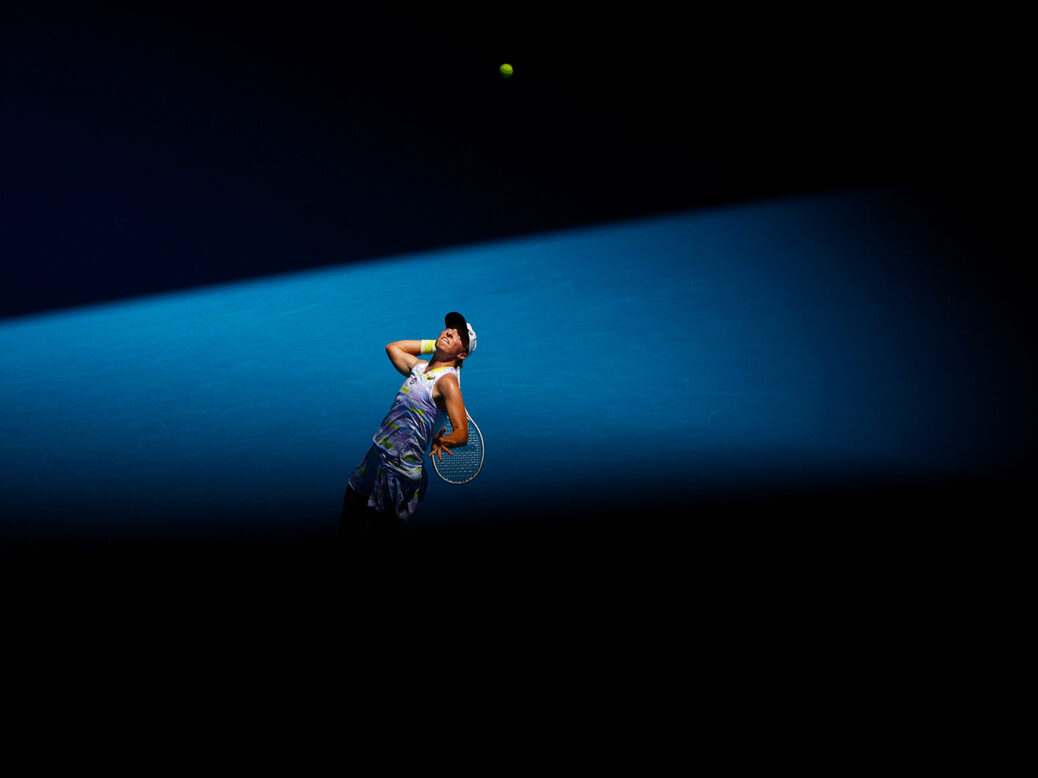

The genius of Iga Swiatek does not reveal itself in an instant. She is neither a physical freak nor a flamboyant risk-taker. Her technique is robust rather than refined, compact rather than exuberant. To grasp what makes the world No 1 from Poland so good, you need to spot the small details. The deceptive power she generates from her 5ft 9in frame. The way she constructs points, gradually pushing opponents further and further out of their comfort zone. She has a deep topspin forehand to make you retreat, and a gossamer drop shot to punish you for retreating. These are the attributes behind the astonishing rise of a player who, at 20, may be the finest women’s tennis player since the prime of Serena Williams.

On 23 May, Swiatek beat Lesia Tsurenko of Ukraine 6-2, 6-0 in the first round of the French Open. It was her 29th straight victory on the tour, a run of dominance in which she has won five consecutive tournaments and beaten most of her main rivals. Already, the discussion is not about whether Swiatek will win in Paris, but who she might face in the final, who might conceivably beat her in the future, how long her reign will last.

[See also: How Peng Shuai exposed the limits of China’s power]

If this seems a touch excessive for a player who has won only one Grand Slam, it helps to understand the landscape Swiatek entered when she joined the tour three years ago. Since Williams won her last Grand Slam in 2017, women’s tennis has experienced a period of unprecedented openness. Emma Raducanu’s win at last year’s US Open felt like a stunning anomaly, but in fact it was largely in keeping with a sport that has thrown up numerous breakthrough stars, surprise winners and one-hit wonders over the years. The last 21 Grand Slams have had 14 different winners.

Occasionally, briefly, some women have threatened to turn their initial fire-streak of success into a lasting dynasty. The brilliant Naomi Osaka looked like becoming the new face of the sport after winning four Grand Slams in 29 months, but has regressed on the court after taking prolonged breaks to protect her mental health. The torch passed to Ash Barty of Australia, who was world No 1 for almost three years either side of the pandemic. But in March, Barty shocked the world by announcing her immediate retirement at the age of 25, claiming she no longer had the “physical drive or emotional want”, and pronouncing herself “spent”.

Over time, women’s tennis has almost internalised this sensation of permanent impermanence: the precarity of knowing that what feels certain today can evaporate in an instant, that stardom and form are fleeting and that a career at the top is an impossibly fragile thing. Heroes and saviours are crowned overnight, and then brought down almost as quickly. The physical and emotional demands of upholding an elite level of performance in a lonely 12-month global sport, living adrift from loved ones, floating from practice court to hotel room to airport to hotel room to practice court, form an almost impregnable barrier to sustained success. For many of the young women at the centre of this world, dealing for the first time with an explosion of scrutiny and interest, the pressure to maintain their level of tennis, their physical fitness, their off-court obligations and their sanity all at the same time can be unbearable. Many have been bruised or broken by it.

[See also: Women’s sport is growing fast – but so is the dominance of a few elite teams]

Sofia Kenin was anointed as the new star of American tennis when she won the Australian Open in 2020, only to succumb in the second round the following year. “My head wasn’t there,” she wept afterwards. “I knew I couldn’t really handle the pressure.” Stricken by an unfortunate run of injuries, she is now ranked No 147 in the world. Bianca Andreescu, the 19-year-old first-time winner of the US Open in 2019, has missed most of the past three years through recurring knee injuries. Raducanu, for her part, has had her own injury struggles, cycled through coaches and won only nine of her 21 matches since winning the US Open.

For a while, it looked as though Swiatek might meet a similar fate. After winning the French Open in 2020 as a 19-year-old unknown, she spent the next few months pounding the tour trying to build her profile and accumulate ranking points. By the time she was knocked out in the quarter-finals of her title defence the following year, she was drained. “When I close my eyes, I only see tennis courts and balls,” she lamented.

But Swiatek had also learned a thing or two from her predecessors. She is one of the few players to have a full-time psychologist, Daria Abramowicz, who often travels on tour with her. She speaks openly in the media about the importance of mental health, recognising her own emotional triggers, embracing her natural self-doubt. In a sport that frequently drags its athletes in a hundred directions, that forces them to become self-run businesses at a ridiculously young age, Swiatek has succeeded by prioritising herself.

She may not win in Paris – although on the basis of bookmaker and pundit opinion, it would be an almighty shock if she didn’t. But watching her on court, you glimpse something even more important: the relish and enjoyment of hard work, the satisfaction of thinking her way through a match, the pleasure of a well-honed process. The real lesson isn’t that Swiatek wins. The lesson is that she’s happy.

[See also: English cricket is in a deep crisis that the ritual sacking of a few coaches won’t fix]

This article appears in the 25 May 2022 issue of the New Statesman, Out of Control