A few months after Freddie Mercury died, my mother took me and my brother to his house in Logan Place, Holland Park, to pay our respects. The Edwardian mansion, built in 1908 for the painter Cecil Rae and his sculptor wife Constance Halford, stands behind a high wall which reveals nothing of what’s inside. At that point, in the early 1990s, the wall was covered in graffiti, much of it from Italian and Spanish Queen fans. In the years after Mercury died, at least in my experience as a teenager, Queen weren’t in the conversation much despite their huge commercial presence and obsessive fanbase. A subtle but undeniable arm’s-length policy hung around them, the legacy of a far less subtle antipathy in the British music press and years of tabloid homophobia. Up there, amid the ivy, was the small bathroom window through which the Sun trained a long-lens camera while Mercury was dying. This mews was where paparazzi camped out, 24 hours a day, till 24 November 1991.

Mercury lived at Garden Lodge with his cook, Joe Fanelli, and his gardener, Jim Hutton, who was also his final partner – the former died of Aids, the latter lived with HIV until his death from cancer at 60. By the time I stood outside the house at the age of 13, the person living inside was Mary Austin, his best friend and first love, to whom Mercury had left everything. Soon the graffiti was scrubbed off and the wall covered in plexiglas: a process she repeated again and again down the years. It didn’t seem like a generous gesture at the time, but you suppose the graffiti was just another intrusion. You pictured her in there in the subsequent three decades, Havisham-like, among his things – the huge collection of Lalique glass, the Matisse prints, the catsuits. Now she has decided to sell them all off in one go. By way of explanation, Austin, a woman of few words, simply says, “It’s time.”

This is the largest single-collector sale Sotheby’s auction house has had in years. In the era of the V&A’s David Bowie Is – the contents of which will soon be housed in a permanent site in Stratford – the vast haul, worth more than £6m, could easily fill a museum: the Sotheby’s sale recreates living and dining rooms and kitchen, and features, upstairs, most of his costumes, and almost every item of his clothing ever seen in a photograph, including the brown fur jacket worn during a performance of “Killer Queen” on Top of the Pops and the red satin number with eyes from the video for “It’s a Hard Life”, known colloquially as the giant prawn. There is a Picasso print, Jacqueline au chapeau noir. His records, his bar and his bar stools are here; his 1950s jukebox too. In the last ten years or so, the critical perspective on Queen has been entirely overhauled and the remaining active members of the band, Roger Taylor and Brian May, have become national treasures. But one wonders whether Austin’s decision not to turn the contents of Mercury’s home into a museum is a residual trace of their difficult time with the press, suggestive of some lack of confidence in the legacy. Or perhaps she could just do with the money.

[See also: Band on the rise: Paul McCartney’s candid Sixties photographs]

But the decision to sell it off to hundreds of different households is democratic in a funny way. Freddie Mercury’s Tiffany moustache comb, complete with case, has a temptingly low reserve of only £400: anyone who loved him enough might own a bit of Freddie forever (in truth it will go for much more). Other pieces are marked far higher – like a Tissot painting, Type of Beauty (1880), depicting the artist’s mistress, estimated at £400,000 to £600,000. If Mercury’s things were made into a museum, it would be a kind of Leighton House affair – the treasures of a single collector with decent taste for a rock star, and regular private access to Sotheby’s after hours.

He once said that collecting was a “sort of shy outlook”. Though his possessions were amassed over years (on days off between shows around the world, he’d always go shopping), he did not really settle into Garden Lodge until the final months of his touring career. There are photos of him painting the decorative cornice in the dining room by hand, in the late Eighties, with a tiny brush. There are items relating to Queen on sale – lots of lyrics, including an autographed draft of “Bohemian Rhapsody” expected to sell for £1m, and a copy of the words to “Don’t Stop Me Now” found just a few weeks ago in his embroidered double piano stool. But most of the stuff in the auction shows another side to him. One large collection is the art nouveau etchings of Louis Icart – loads of them: women with butterfly wings, graceful greyhounds, furred glamorous ladies with feather boas; and there are oil portraits of Gypsy women in vivid shawls and garlands of flowers. Mercury surrounded himself with the female form and the faces of women and children. On reflection, you can see in his taste for graphic art the roots of his own drawings at the Ealing School of Art, which he adapted into the early Queen logo comprising the band’s star signs, with two nymphs representing Virgo, for Freddie.

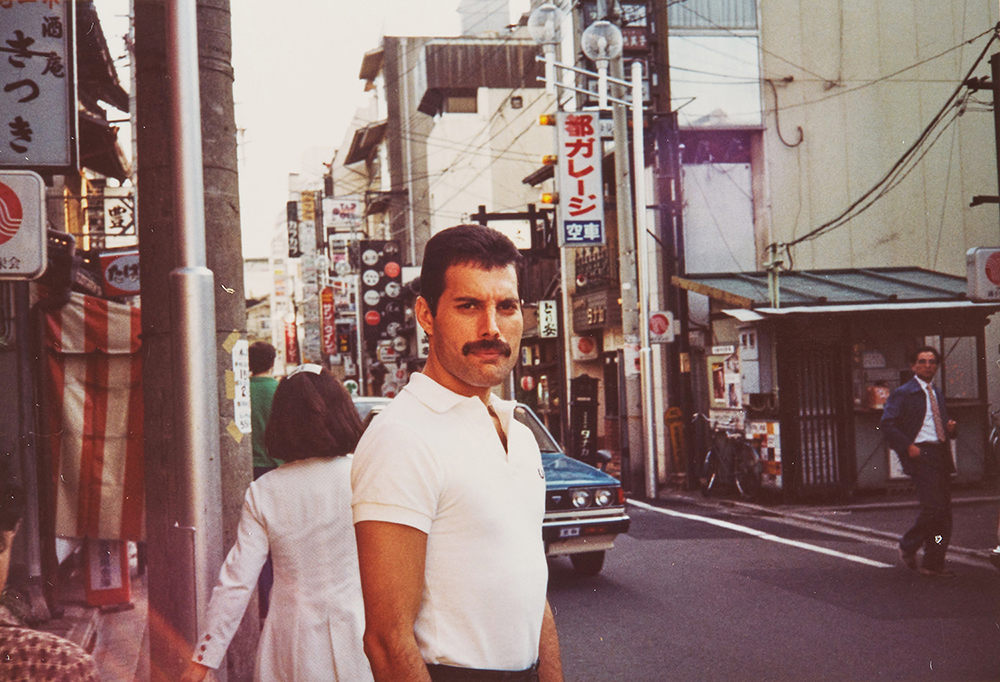

His ground-floor drawing room was called the Japanese Room. Billed as one stand-alone sale, it might be aimed at a different market from the sequined catsuits and 1986 Adidas boxing boots (so very light, and really not that expensive). There are ukiyo-e woodblock prints (think the Hokusai wave), some of which he bought at Sotheby’s to start with (his PA would arrive at auction houses with a blank cheque, shouldering new pieces out into a van the same night). One 1857 woodblock, called Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake was admired by Van Gogh, and the estimate is £30k-£50k.

The less pretty stuff is more intriguing, more lived-in, such as his enormous dresser in the kitchen, a pine eyesore, and, next to it, a heavily worn table and six pouffes to sit on with green, split leather tops. A large collection of contact sheets credited to the photographer Mick Rock (£5,000-£7,000) shows the parties Freddie got up to at home: half a dozen moustachioed pals in kimonos with Anita Dobson in the middle. The recreation of his little minstrel’s gallery also has a human touch. He was not much of a reader – he preferred magazines – and the titles on his bookshelves (yes, even the books are going) are surprisingly blokey: Flashman novels, World of Krypton, a collection of rugby songs.

Ultimately we didn’t know Freddie Mercury. He gave up on interviews early on in his career. His social life was secretive because of his sexuality, his lovers often ordinary people – tradesmen, waiters – many of whom seemed unimpressed by his fame. Despite attempts at a solo career he was loyal to his band, and his band were a closed shop. During his lifetime he wasn’t written about or analysed with any great depth and consideration. In recent years, his closeted life and death have been understood with compassion but it’s too late to get a sense of what he was really like – in that living, breathing, self-curating sense we have of celebrities today. Now, you can take a little piece of him home with you, whoever he was, if you have a few thousand. Whether it’s a 1934 chinoiserie baby grand piano, or an early-Eighties hardback copy of Dune.

The free exhibition “Freddie Mercury: A World of His Own” is at Sotheby’s, London, 4 August – 5 September, with auctions running 6-13 September

[See also: A history of Spain in 150 objects]