Animal Collective – Time Skiffs

For valiant Animal Collective fans, the arrival of a new album by the experimental Baltimore band brings more trepidation than excitement. Will it, like Merriweather Post Pavilion (2009) and Painting With (2016), be a dreamy cartwheel through their Beach Boys on blue Smarties sound – all textured vocal harmonies and weird refrains (“I just want four walls and adobe slats for my girls” and, just as poignant, “Flori, Flori, Flori, Flori, Florida/Florida-da/Florida-da”)? Or will we be subjected to another Tangerine Reef (2018), a tedious audio-visual album seemingly inspired by tinny loudhailers and the screech of dial-up internet? With Time Skiffs, Animal Collective – recording again with founding member Noah Lennox (also known as Panda Bear) – have resurrected the surf-noir bubbles of pop with which they broke into the mainstream in the late Noughties. From the hypnotic slow-burn of “Prester John” to “Cherokee”, an ethereal and reverb-fuelled ode to road-tripping (“On a tour I saw focaccia treated like it’s jade”), the band is back to just the right level of wacky.

Anoosh Chakelian

Bastille – Give Me the Future + Dreams of the Past

With its raspy, synth-heavy soundscape and anthemic melodies, Bastille’s fourth album, Give Me The Future + Dreams Of The Past, explores our complicated relationship with technology. Here, society’s conflicting desires – how do we embrace new frontiers, while preserving the sanctity of now? – are laid bare. Want blissful ignorance? Snatch a VR headset, grab a loved one and relive nostalgic pop-culture in the zany track “Thelma + Louise”. Or, if you’d prefer to bask – or spiral – in today’s crises, then and hear frontman Dan Smith list the anxieties of modern life in “Plug In”. Throughout, Smith’s commentary emphasises our need for human connection above all, exemplified by the acoustic, standout track “Hope For The Future”.

Harry Clarke-Ezzidio

Beyoncé – Renaissance

At the beginning of this year, we were informed online that a “vibe shift” was occurring. Gen Z swarmed. Boomers scoffed. Those of us in between laughed nervously and pretended to understand what was going on. Which is to say, it was manufactured – vibes, perhaps, for vibes’ sake. But how naïve we all were. On 21 June, Beyoncé dropped “Break My Soul”, naked atop an iridescent horse, and created less a vibe shift, and more a vibe overhaul.

We have come to expect surprises from Beyoncé, the most culturally powerful artist working today, and this – the lead single from her album Renaissance – was no exception. Based on a sample from Robin S’s house classic “Show Me Love”, “Break My Soul” was a blueprint for this album, which celebrates, revives and elevates classic dance music. Packed with pounding beats, vintage brass, hidden vocal gems and samples from Right Said Fred to Donna Summer, this is a tribute not only to the dancefloor but the queer culture that uses it as a stage.

Emily Bootle

Björk – Fossora

Only Björk could make a record about fungi sound this good. While the flute was the Icelandic artist’s instrument of choice on her previous album, Utopia (2017), Fossora is all about the bass clarinet. The instrument’s reedy tone anchors these songs to the natural world, the place to which Björk looks for hope. Every Björk record is a work of visionary expanse, but Fossora – despite its comparative sonic sparseness – feels more intricate than ever. On each listen I become aware of a new lyric – most recently it was “For millions of years / We’ve been ejecting our spores” – or a crunchy new timbre. But after tens of listens, two tracks always stand out to me: “Sorrowful Soil” and “Ancestress”, a pair of songs written to commemorate Björk’s mother, the environmental activist, Hildur Rúna Hauksdóttir, who died in 2018. Ten albums in, Björk knows to look to the past as well as the future, and to the earth beneath her feet as much as the skies above. Her resultant sonic landscapes are utterly poignant.

Ellen Peirson-Hagger

Black Country, New Road – Ants From Up There

For the few years they’ve been on the scene, Black Country, New Road – a cacophonous, seven-piece band comprising prodigious multi-instrumentalists aged under 25 – have represented the new and exciting in British music. When they announced their second album in late 2021, it felt like something big was about to happen. And then, in late January 2022, four days before Ants From Up There was due for release, something even bigger happened. The lead singer of the band, Isaac Wood, announced he would be leaving due to mental health problems.

This was, in a way, a catastrophe: the band’s sonic identity is closely bound up in Wood’s resonant, emotive vocal and experimental lyrics. Yet it also made Ants From Up There feel more profound. As the record screeches through anguished, semi-ironic proclamations – “She had Billie Eilish style/Moving to Berlin for a little while” – what comes through is a deep sadness, which ebbs and flows with the tempo changes and dynamic swells. Eventually we reach “Show Me the Place Where He Inserted the Blade”, where Wood sings: “Every time I try to make lunch / For anyone else, in my head / I end up dreaming of you”. Could that not be the most romantic lyric you’ve ever heard?

Emily Bootle

Ethel Cain – Preacher’s Daughter

Last year, from a converted church in rural Indiana, Hayden Anhedönia told Pitchfork that she was working on “the next great American record”. The resulting album, Preacher’s Daughter by Anhedönia’s ethereal alter-ego Ethel Cain, is a sweeping Southern Gothic epic that spans pop, country, gospel, rock, and folk, but retains a disarming intimacy throughout. Anhedönia, a trans woman raised in a claustrophobic Southern Baptist community, has a complex relationship with faith and family – here channelled into the “cautionary tale” of the sad, spectral Cain, who escapes from a religious cult to roam the country alone. There’s a touch of Lana Del Rey in Cain’s rendering of faded Americana: all roadside motels, parking lots, motorcycles and pick-up trucks. Absent men cast a long shadow over this landscape: a dead father, ex-lovers, an elusive Jesus.

The single “American Teenager” uses John Hughes’ Eighties synths and effortlessly catchy melodies to characterise suburbia as a warzone with schoolkids on the front lines. The influence of Anhedönia’s childhood hero, Florence Welch, is audible in the theatrical drums and building vocals of “Thoroughfare”. And on “Sun Bleached Flies”, the religious music of her upbringing is transmuted into shimmering choral harmonies over sparse piano: “What I wouldn’t give to be in Church this Sunday”, Cain sings, “Listening to the choir, so heartfelt, all singing: ‘God loves you, but not enough to save you.’”

Anna Leszkiewicz

Jessie Buckley and Bernard Butler – For All Our Days that Tear the Heart

Often, we use a work’s prescience to talk about its quality. Our shared cultural psyche tells us that timeliness – the sense that a book could only have been written during the pandemic, a film only developed post #MeToo – is what it’s all about. But it is timelessness that is the defining characteristic of For Our Days that Tear the Heart, the debut record by the Irish actor Jessie Buckley and the guitarist Bernard Butler, who was Suede’s first guitarist. When I saw them perform these songs at Green Man Festival in August, Buckley sang with her feet shoulder-width apart, her hands on her hips. The resultant voice was – as it is on the record – rich and deeply felt. The 12 songs are contemporary folk numbers: Buckley sings of loss, pain, the utter purposelessness of life. With Butler’s elegant production and searing orchestral arrangements, they become glistening artefacts of humankind.

Ellen Peirson-Hagger

First Aid Kit – Palomino

Klara and Johanna Söderberg, the Swedish sisters of First Aid Kit, say they’re actually quite scared of horses. But they settled on the album name Palomino – a horse with a golden coat – as a “symbol of strength and freedom”. In the 14 years since they first uploaded their cover of a Fleet Foxes song to YouTube (they were then aged 15 and 17), they have released a series of well-received albums. But what I love about their fifth is that, now, you sense they have lived the songs they’re singing. They are no longer just playing country-folk: this album is a little bit Kate Bush, a little bit Fleetwood Mac, and a lot unapologetically themselves. “Out of My Head” will make you dance around the kitchen. “Angel” is for vanquishing self-doubt. There is melancholy and heartbreak (“Nobody Knows”, “A Feeling That Never Came”). By the time you get to the glorious final track “Palomino” – “Gonna let the sun shine down / I’m heading out to roam” – you will feel like riding off into the sunset, whether you like horses or not.

Katie Stallard

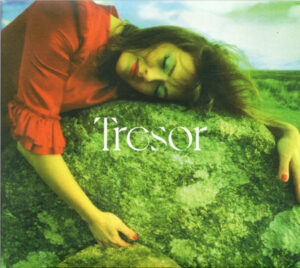

Gwenno – Tresor

For a record about inner life, Gwenno’s Tresor has extraordinary breadth. You might expect the Welsh artist’s second Cornish-language album to trace a psychedelic, pastoral thread from Vashti Bunyan and John Martyn through to Boards of Canada, by way of Bwyd Time-era Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci, and SFA’s Mwng. But Gwenno and producer Rhys Edwards also include so much that surprises – there’s the smoky campfire soul of the title track, like a lost 1960s torch song; the motorik rhythm on “NYCAW” (sung in Welsh); and the ambient drifting “Tonnow”, which recalls the instrumental second side of Bowie’s Low. Throughout, the percussive bass and spare flourishes evoke the elegant, just-so pop of Wild Beasts circa Present Tense. The real star, however, is the beautiful, undulating sound of the Cornish language, which through Gwenno sounds not merely revived but utterly contemporary. Res koedha yn nans rag sevel arta.

Peter Williams

JID – The Forever Story

In the run-up to releasing this album, the American rapper JID released several singles that I played on repeat. Both “Surround Sound”, featuring 21 Savage, and “Dance Now”, with Kenny Mason, dominated my playlists. I loved these tracks so much, I worried that the full record wouldn’t live up to them. When the album appeared, my worries were quickly dashed. The Forever Story, JID’s third solo album, is a seamless mix of hip-hop bangers and R&B melodies that demonstrate his already proven rapping talents as well as his newfound singing range. The record is strongly centred around JID’s relationship with his family, from the intriguingly non-linear recollection of a club-night brawl with his siblings on “Crack Sandwich” to the nostalgic reflection on a baloney-eating childhood gone by on “Money”. This album is hype track after hype track, but knows how to get emotional when it wants to.

Hugh Smiley

Jenny Hval – Classic Objects

On Classic Objects the avant-garde artist Jenny Hval takes a critical approach to the typically introspective lockdown album and re-examines herself as an artist. The jaunty, slinky opener, “Year of Love”, describes a Hval concert at which she intended the audience to feel like they had dissolved under the disco lights and belonged to no one in particular. Then, during what she describes as a “song I thought I knew what was about”, a man in the crowd proposed to his girlfriend. Ultimately she accepts that she has lost control of her meaning. “When I listen deep, I’m not my owner,” she sings on “Freedom”. Hval turns the focus from herself to the social and political contexts that contribute to people’s inner lives. The sparse synthesisers and guitars open out into something lush, expansive drumming lifting the centrepiece “Jupiter” into an art-pop epic.

Matthew Gilley

Jóhann Jóhannsson – Drone Mass

The late Icelandic composer Jóhann Jóhannsson was probably best known for his scores for films such as Sicario and Arrival, and in his non-film work you can easily see what might have attracted directors to his music. Drone Mass, which recalls the “holy minimalism” of Arvo Pärt or John Tavener, is all space and tension. It achieves indelible effects with limited materials. Jóhannsson sets Coptic texts for chorus with string quartet; humming, buzzing electronics reference drone warfare. Cyclical melodies and sustained glissandi pass between voices and strings; meaning is circled without ever being settled on. This is a sublime work that could easily have been lost: the electronic part had to be recovered from files on Jóhannsson’s computer after his death in 2018. It is a relief that it was possible.

Matthew Gilley

Kendrick Lamar – Mr Morale & The Big Steppers

Is there a more thrillingly inventive musician at work today than Kendrick Lamar? Having unlocked the writer’s block that followed Damn in 2017 – the first pop record to win a Pulitzer Prize – the Californian rapper has produced a double album that does not so much up his game as entirely change the rules. Over the two hours of Mr Morale & The Big Steppers Lamar turns inwards, applying his unique form of brutal poetic candour to himself and his family, against the backdrop of a dysfunctional America and crisis-ridden planet. At every turn, love and faith coexist with trauma and violence, a conjunction reflected not only in the lyrics – “Playing ‘Baby Shark’ with my daughter/Watching for sharks outside at the same time” – but the music and vocals, which veer from plaintive pianos and singing (guests include Beth Gibbons of Portishead) to stinging expletives and beats pulsing with barely suppressed rage. Like great American poets before him, Kendrick Lamar contains multitudes.

Tom Gatti

Linda Hoover – I Mean to Shine

In the summer of 1970, Linda Hoover had made it. The 19-year-old had just recorded one of the best albums of the year, backed by a gang of gifted musicians who would later go on to form Steely Dan. Laurel Canyon and a sunlit future in the Seventies singer-songwriter boom beckoned. And then: nothing. Following a spat between Hoover’s producer and her label over publishing rights, the project was abruptly cancelled, her career stalled, and the record was left to rot, unpressed and unheard.

Its surprise release in 2022 was a happy ending of sorts, though of the supremely bitter-sweet variety. On its own terms Hoover’s album – which includes five early songs written by Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen and Walter Becker – is a vacuum-sealed time capsule that captures the transition from Sixties folk to the jazz-chops sophistication of the Seventies, her honeyed delivery hitting the precise midpoint between Joan Baez and Karen Carpenter. But validation for Hoover has come 52 years too late, and all the innocence and promise that glimmer throughout I Mean to Shine make every song on it a heartbreaker.

Chris Bourn

MUNA – MUNA

Muna, the band, came out with Muna, the album, in June. Their third record – and their first to be released on Phoebe Bridgers’s Saddest Factory label – marks an evolution. The synth-pop band’s first two albums – About U and Saves the World – wallow in heartbreak and sadness. Their latest isn’t exactly happy, but the songs are about what happens when you give yourself credit. “Home By Now” is about wondering what might have been had the narrator accepted less. “Loose Garment” is about what happens when grief and pain don’t go away, but ease up. There’s a real defiance here. “You’re gonna say that I’m on a high horse. I think that my horse is regular size,” they sing on “Anything but Me”. Muna and their music are unapologetically queer. “I wanna dance in the middle of a gay bar”, they sing on “What I Want,” adding, “There’s nothing wrong with what I want.” “We’re for the queerful joy revolution,” the lead singer Katie Gavin told the crowd at the band’s Washington DC concert this autumn. She had misspoken, but she wasn’t wrong.

Emily Tamkin

Oliver Sim – Hideous Bastard

The debut solo album from the XX’s Oliver Sim is a deeply personal study of shame and identity. Starting with “Hideous”, he tackles the stigma of his HIV diagnosis and its effect on him, with beautiful, haunting melodies that build to a plaintive cry. This exploration of self-esteem continues throughout the album. “Saccharine” is a heartfelt song about the barriers you put up to keep others out; “GMT” shows the power that love can have to help and hurt, even – and especially – when you’re miles apart. The album brings the same electronic, slightly surreal production that we know from the XX. But Sim – along with Jason XX, who produces here – knows when to use the production as a shield to hide behind and when to lower it to expose the rawness of his emotion. This is a fantastic debut from someone who has for a long time had a lot he’s wanted to say.

Adrian Bradley

Sharon Van Etten – We’ve Been Going About This All Wrong

“Been writing on the dust/I’m hearing stars fall”, sings Sharon Van Etten as her sixth album’s opening track, “Darkness Fades”, begins to swirl. The line is a reference to the embers that caked her car, blown in from the wildfires raging close to her LA home in 2020. That burning sky is sublimely replicated in We’ve Been Going About This All Wrong, much of which Van Etten put together under Covid restrictions in the studio in her garage. As ever, her writing focuses candidly on her own life, here sketching scenes of parental guilt and waning domestic intimacy. But the cinematic production, thick with reverb and ethereal synths, and her airborne vocals, rising euphorically in songs such as “I’ll Try” and “Born”, give Van Etten an epic scope not heard on her previous records. This is an album loaded with the claustrophobia and apocalyptic anxiety of family life in lockdown – but transfigured into something that’s expansive, lit by hope and completely magnificent.

Chris Bourn

The Smile – A Light for Attracting Attention

Short of styling itself A liTE for AtraKTing a Tent-ION, it’s hard to see how the Smile’s debut record could be any more Radiohead. There’s Thom Yorke’s voice, at turns querulous and sweet, delivering cut-up stock phrases and obscure barbs; there’s the casual brilliance and clarity of Jonny Greenwood’s guitar. Nigel Godrich produces, Stanley Donwood does the sleeve. The only obvious difference is Tom Skinner bringing a softer, more understated touch on drums.

Fans will play Radiohead bingo – “The Same” evokes “Everything in its Right Place”, “Free in the Knowledge” a slightly more chill “How to Disappear Completely”, and the simple descending figure of “The Smoke” the old B-side “Talk Show Host”. But ultimately, the Smile offer a continuation of the warm, woozy textures of 2016’s A Moon Shaped Pool, as well as its bursts of dense, dazzling orchestration. For all its expression of anxiety, anger and sadness, this is also a record at ease with itself, an unstrained-for cohesion. If big rock music is even still a thing, then it is also still true that Yorke, Greenwood and co are miles ahead of the rest. As you were for the past 25 years, then.

Peter Williams

Taylor Swift – Midnights

Taylor Swift has built a career from self-reinvention. So when Midnights arrived lacking a fresh haircut or style switch-up, it felt like the popstar was pausing for a moment of reflection. After the folksy detour of her pandemic albums, Midnights is a jolting return to pop – complete with vintage synths and diaristic storytelling. It’s her most self-loathing and most honest record yet, but above all, it’s a lot of fun. Forgive the odd slightly questionable lyric – “Karma is a cat, purring on my lap cause it loves me” – and look instead to the places Swift cleverly references her own back-catalogue. “Could’ve Would’ve, Should’ve” is a cathartic bookend to her song about her painful relationship with John Mayer, “Dear John” (2010), and a conclusion she only could have written now, with the wisdom experience brings. On “Question…?” she borrows the beats, drum samples and some lyrics of “Out of the Woods” (2014) and the result is a far cooler, brooding track. Many stars say they dedicate albums to their fans, but Midnights truly feels made for those who have followed Swift since they were in their childhood bedrooms.

Ellys Woodhouse

Frank Turner – FTHC

I understand if punk rock doesn’t sound like your thing – this time last year I would have felt the same. Then Frank Turner’s ninth album landed in February and everything changed. FTHC is a soundtrack against which to work out your pandemic trauma – something Turner left no doubt about at Brixton Academy on his post-Covid tour. “Well fuck last year / I’m glad it’s done,” he roars on “Punches”, channelling the emotional rawness of a nation that has quite simply had enough. “I Haven’t Been Doing So Well”, meanwhile, is a frenzied exploration of anxiety that is sure to resonate after the hopelessness we have all endured since 2020.

But it’s the cheerful, toe-tapping electro-rock of “The Work”, a song Turner wrote for his wife, that really got me: “I want to visit the coast in Kent with you on a weekday afternoon when we’re both retired.” I belted out the words, alongside the man I married six months previously, at our first gig together. I genuinely don’t think I’ve heard a more romantic line. Who said punk rock wasn’t meant for love songs?

Rachel Cunliffe

The 1975 – Being Funny in a Foreign Language

Does any band capture the spirit of the internet generation better than the 1975? Their latest album, Being Funny in a Foreign Language, is no exception. It sounds as though Matt Healy, the band’s self-proclaimed “ironically woke” “post-coke” frontman, has passed the tracks through a Gen-z buzzword generator. He uses the clichés of the TikTok generation – Aperol, gaslighting and “vaccinista tote-bag chic baristas” – to encourage a rejection of social media vapidity in return for the truest form of human connection: love.

Among the cynicism, the 1975 retain their unparalleled genius for describing the having, losing, and wanting of love with the straightforward sincerity of the young. “About You” is a haunting track, mourning the memory of a lover. “Looking for Somebody (to Love)” is the standout bop of the album, complete with Eighties synth and a catchy chorus. But closer inspection reveals a frightening song about inceldom and male rage. This album holds up a fragile mirror to modernity, begging us to smash it.

Zoë Grünewald

Explore our other 2022 Culture round-ups: