Inside a vast unit in a manufacturing park just outside Middlesbrough, the flag of Cuba hung off a tower of scaffolding. Below it, looking up, stood three men on a floor that had been painted the exact blue of the Tees Transporter Bridge.

The flag’s communist connotations “nod to the fact that we want to service everyone in a fair way”, said David Todd, one of the co-directors of Press On Vinyl, a new pressing plant aiming to right the supply crisis in vinyl record manufacturing, which has left the industry struggling to provide artists and customers with vinyl editions of new releases.

“No customer will be treat differently,” said his colleague Danny Lowe in a Teesside accent. He recounted a phone conversation the business’s marketing manager had with a broker – an agent who liaises with pressing plants on behalf of record labels. The broker asked that the plant produce a certain number of records by a fixed date, for a low price. The marketing manager insisted Press On’s prices were non-negotiable. Lowe recalled: “And the broker said, ‘Well, that’s a terrible business model, but if you want to become the communist pressing plant of Teesside, you crack ahead.’”

“The plant was set up to be part of the solution, not the problem,” said David Hynes, the company’s third director.

“So we thought, let’s get that flag up there!” laughed Lowe.

As the New Statesman reported in September, vinyl sales are at their highest since the early 1990s. But current supply can’t keep up with demand, and manufacturing delays are making the operation unfeasible for many artists and labels. The biggest losers in the current market are independent labels and musicians, who can’t compete with the hold major labels have over plant capacity. What’s more, shortages of materials such as PVC, a crucial component in vinyl records, are pushing prices up for pressing plants – and for consumers too.

Press On Vinyl, which is due to open for business in the new year, will be Teesside’s first vinyl pressing plant, and one of just a handful currently in operation in the UK. Todd, who previously worked in ship mooring on the River Tees, Hynes, who runs his family’s fire alarm business, and Lowe, who has worked on and off for that fire alarm business for 20 years, are huge indie music fans. Todd and Lowe previously ran a small label, used to host a club night, and have built recording studios above Middlesbrough venues.

Their business model speaks to their interest in grassroots artists: they will take orders from new artists who aren’t signed to a label at all, as well as from the subsidiaries of the bigger independent label groups. They will press records in runs up to 2,000, and starting at just 100, a quantity that most plants don’t offer at all. “There’s loads of artists and smaller labels who can’t afford the bigger runs, so can’t get their records pressed anywhere, never mind the delays,” said Todd, as he sat in the freshly painted reception area of the unit in mid-October. “Hopefully we’ll be giving more artists a look-in.”

“And there won’t be ‘deals’ for anyone,” added Lowe, firmly.

Crucially, clients won’t have to join a years-long queue. “We’re aiming to have test pressings back to people within a month,” Todd said. “And then we’re aiming to keep our lead times to no more than three months, from receiving the files to delivering.”

Recent decades have also seen a decline in manufacturing in Middlesbrough, something the team, whose unit aptly sits on the grounds of an old ironworks, hopes to change. Press On Vinyl has nine full-time employees and hopes to grow to 30 by the autumn of 2022.

Lawrence Montgomery, the UK managing director of Rough Trade, told the New Statesman that staff across his shops are selling 50 per cent more vinyl now than before the pandemic. “We would have liked to have seen more investment in vinyl capacity earlier,” but “it’s really great to see additional capacity opening up in the UK”, he said of Press On’s opening.

The desperate need for more pressing plants to match the growing demand for vinyl has led some to question why more plants have not been set up in recent years. “It’s just very hard,” Todd said. It takes significant investment, expertise and specialist equipment, which is proving harder and harder to come by.

“We would love to see the industry as a whole work together to see what they can do to de-risk and incentivise more start-ups in the vinyl manufacturing space,” said Montgomery.

The Press On team is confident that it is not just reacting to a short-lived trend. “We don’t see this – where vinyl has come back in – as the blip,” said Hynes. “The blip was when it went out of fashion.”

Press On Vinyl has received a mix of financial assistance from grants, loans and private investment, including from the live music company Futuresound Group. “I wanted to set up a vinyl pressing plant ten years ago,” Colin Oliver, Futuresound’s managing director, said over the phone. “We even bought two pressing machines in the Czech Republic.” But he went no further: Oliver and his colleagues had great music industry experience, but no manufacturing expertise.

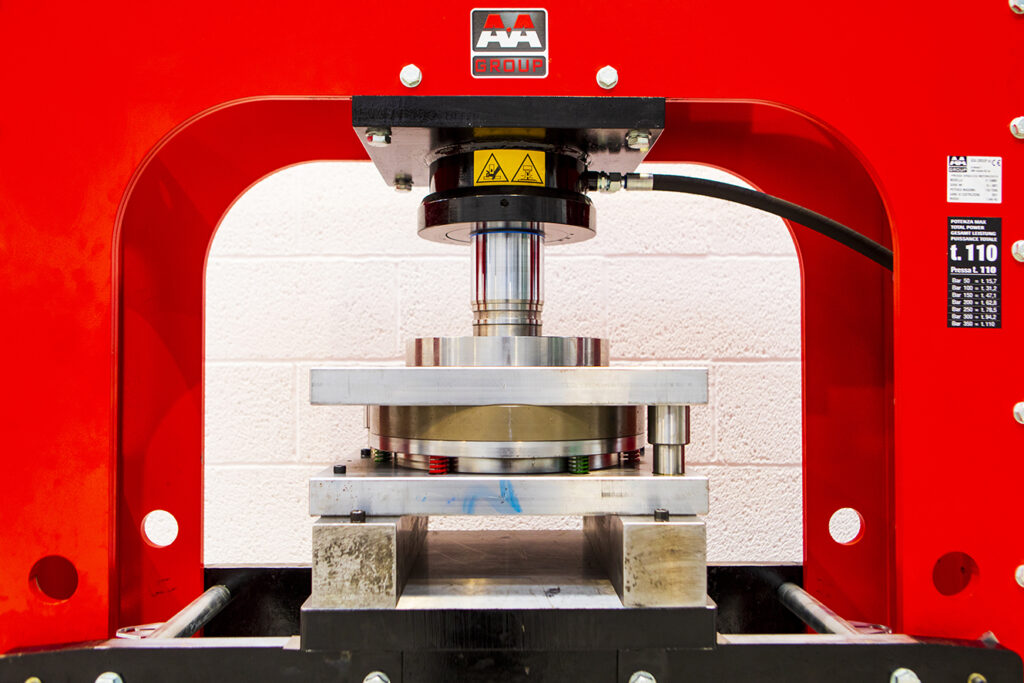

When the pandemic hit, Todd had the time to sit and research the workings of record pressing “all day and night”. Now, thanks to help from external consultants who have been in the business for decades, he’s an expert. He and Lowe walked around the unit talking through the complex scientific processes that go into pressing a record. A lacquer mastercut arrives from the mastering engineer and heads straight into the galvanics room, where an automatic silvering machine covers the disc in fibre solutions. From this, “father” and “mother” stampers are produced in an electro-forming (galvanic) bath – later, they’ll be used to press the grooves into the A and B sides of each record respectively. The disc is sanded and a hand-pulled machine punches a hole in its centre. The stamp is then ready, along with PVC pellets and specially baked centre labels, to head to the pressing machines – which, in mid-October, were still sitting in a shipping container somewhere between Hong Kong and Teesside.

The last 20 months have been “the perfect time to set up a pressing plant”, Todd said, “but also the hardest time to build a factory and to source raw materials”. Brexit has not affected them much, he added, but delays and shortages due to the pandemic have forced the team to regularly reassess deadlines and costs. “PVC went up by about 30 per cent in the summer, and we’ve just noticed that it’s gone up again.”

But the plant is set to be profitable, Lowe said. It has to be, “because we need to be sustainable and we want to grow”. There will be two pressing machines to begin with, rising to six in the coming months. Once the presses start up, they will aim to produce 50,000 records a month, doubling in the first few months and growing throughout 2022. It’s a comparatively small volume: Record Industry, a well-established plant in the Netherlands, presses 50,000 records a day. But it’s a start, and the team are ambitious, hoping one day to have the facilities to record, cut, press and distribute records, “so Middlesbrough becomes a bit of a Detroit”, Lowe said.

Stepping through a hatch to the grey day outside – “It’s never not windy in Middlesbrough!” laughed Todd – Lowe explained the steam generators and air compressor system used to power the pressing machines, and to cool them. The generators will be powered with liquid petroleum gas, but a desire to reduce the plant’s carbon footprint is high on the business’s agenda as it develops.

“We’re already in discussions about the ways we can move as close to renewables as possible,” Lowe explained. “We need to get producing first, but we like to think that in five years’ time we’ll either be running the plant on renewable energy, or we’ll be close.” From the off, the plant will use a grinder to process excess PVC: an estimated 15-20 per cent of the initial compound will be recycled materials.

Some pressing plants – such as Deepgroves in the Netherlands – have already committed to a green agenda. But Lowe was cautious about compromising on quality too soon. One plant he knows of manufactures records with 100 per cent recycled plastic. “But most of what they’re pressing is metal bands – so you don’t notice the quality drop, if you know what I mean,” he said with a grin.

The first record off the presses will be the debut EP by Komparrison, a young, local five-piece who are “the best band round here”, according to Lowe. “They write fantastic, witty songs that are really of the area – you can tell that they’re from the north-east. They’re very real and very funny.”

When Komparrison first began looking into the possibility of pressing vinyl for a future release, they quickly realised how expensive it would be for a band like their’s. So they put the idea “on the backburner”, said Elise Harrison, one of the band’s singers. Now, the dream of releasing vinyl is a reality. “We’re so glad and grateful that Press On Vinyl chose us to be first off the press, not only because we finally have the opportunity to release vinyl, but to work with class people also.”

It was always obvious to Lowe, Todd and Hynes that a local band would be first to have their records manufactured at Press On Vinyl. “We want to shine a light on Teesside,” Lowe said. “It’s the centre of our hearts.”

He continued: “We get beaten with a stick a lot. You go away to places and you tell people you’re from Middlesbrough, and they’re like, ‘Ooh, it’s a bit rough.’ And it’s not like that at all. We’ve got a great community, everybody knows everybody, and there’s a bit of a saying: ‘If you’re sound, I’m sound.’”

[See also: How the vinyl industry reached breaking point]