It must have been early 1987. BBC2 had just broadcast a documentary about Jack Kerouac, which I had taped on to a VHS. By the following week, I had got hold of On the Road and joyously sped through it. But before that, I repeatedly played the part of the film dedicated to Kerouac’s musical tastes, and his elegy to Charlie Parker: “Charlie Parker looked like Buddha… And his expression on his face/Was as calm, beautiful and profound/As the image of the Buddha/Represented in the East, the lidded eyes/The expression that says: ‘All is well.’”

It must have been early 1987. BBC2 had just broadcast a documentary about Jack Kerouac, which I had taped on to a VHS. By the following week, I had got hold of On the Road and joyously sped through it. But before that, I repeatedly played the part of the film dedicated to Kerouac’s musical tastes, and his elegy to Charlie Parker: “Charlie Parker looked like Buddha… And his expression on his face/Was as calm, beautiful and profound/As the image of the Buddha/Represented in the East, the lidded eyes/The expression that says: ‘All is well.’”

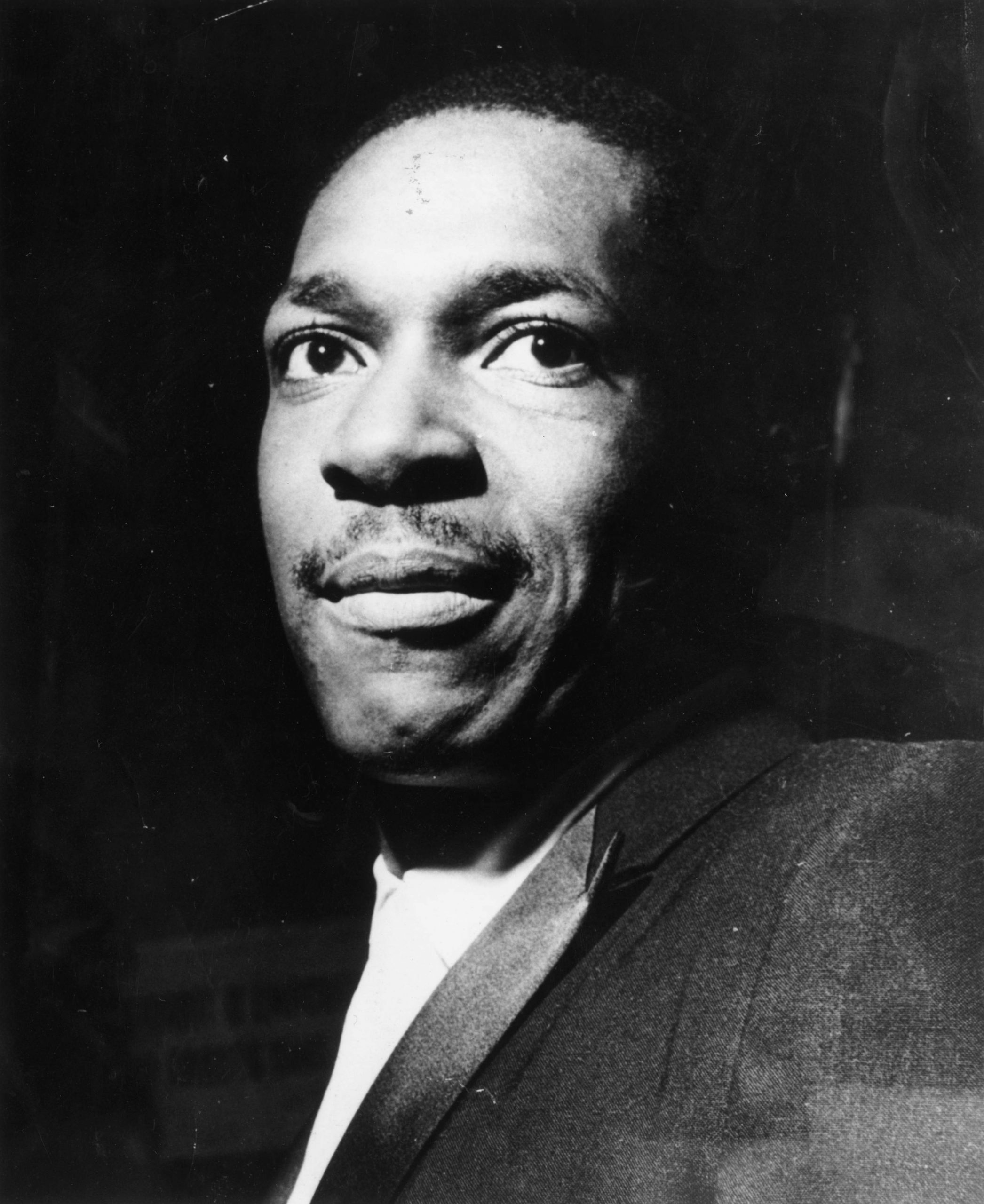

With my sixth-form friend Neil, I decided that now was the time to go beyond indie-rock and hip hop and sample the higher pleasures of jazz. This involved two places: a cut-price vinyl outlet in the backstreets of Manchester where I got two Parker records for £3 a piece; and the library in my hometown of Cheshire, where one album now screamed out to be borrowed. Probably via the NME, I already had some vague notion of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme – released in January 1965, and arguably the composer and sax player’s greatest achievement – as a totem of cool, but now it felt obligatory. It was 25p for two weeks, plus a quid on a TDK C90 tape: a no-brainer, as we didn’t say back then.

Then came another epiphany. This was the most transcendent music I had ever heard. Coltrane’s sleeve notes, which refer to a “spiritual awakening” he experienced in 1957 (“This album is a humble offering to Him…”) must have helped put me in the right mood, but what I divined in the music came to mind with no prompts. This opening mixture of the album’s central four-note motif and McCoy Tyner’s questing piano chords seemed to evoke the night, and rain; the sax part that awakened the track titled “Resolution” after 20 seconds sounded like a sudden dawn; in between, the passage in which Coltrane intoned the title as a mantra was full of a power I couldn’t even begin to articulate. This was heady, elemental stuff.

At Neil’s house, where we spent whole Saturdays immersed in music and eating Lancashire cheese toasties, it worked the same magic; at night, when I would play it on the Binatone cassette player next to my bed, it entranced me even more.

It still does. I feel it as keenly at 47 as I did when I was 17. When the world seems to be reducible to trivia, nastiness and a lack of hope, A Love Supreme gets as close to attesting to a higher power as any record ever has, and seems to offer an eternal assurance: that, on some elevated plane accessible only when the right music plays, all is well.

Read the rest of the series here

This article appears in the 08 Dec 2020 issue of the New Statesman, Christmas special