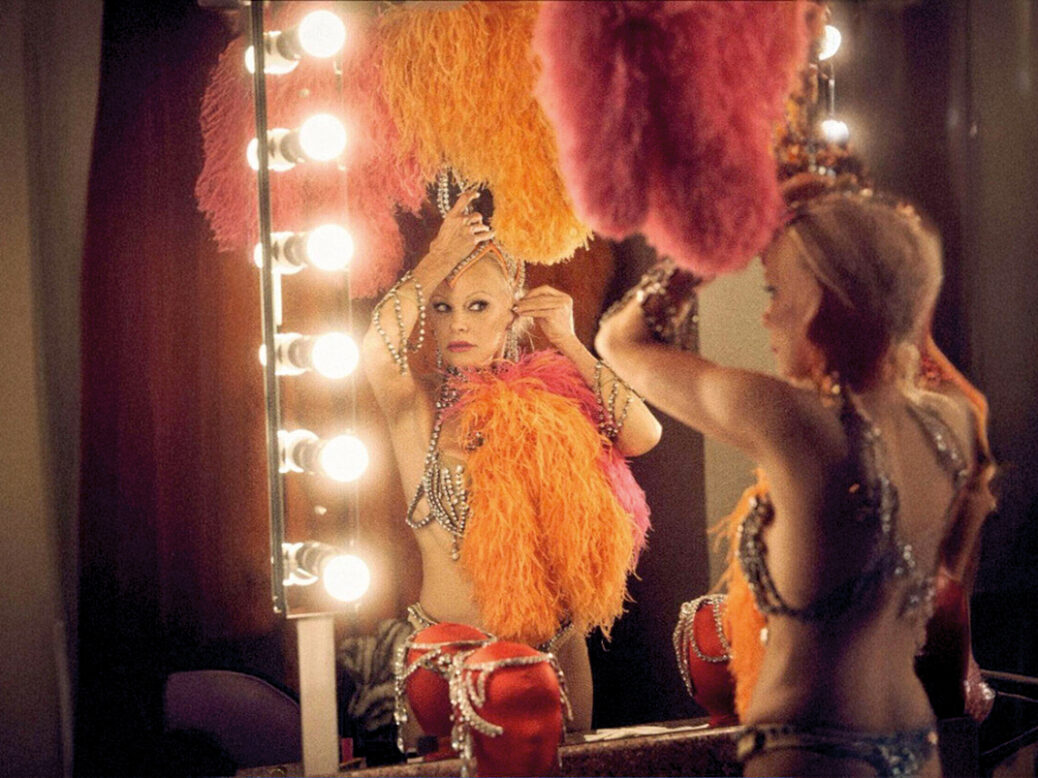

In Las Vegas, audiences for “Le Razzle Dazzle” are dwindling. Shelly (Pamela Anderson) is one of its stars – a blonde dancer who wears a jewelled corset, feather headdress and showgirl’s mile-wide smile. Shelly can’t figure out why the show’s appeal is fading. As she puts it, there’s “breasts and rhinestones and joy!” Isn’t that enough?

For The Last Showgirl it is, though audiences may beg to differ. The third film from Gia Coppola (granddaughter of Francis, niece of Sofia) attempts to seduce sceptics by shooting the spectacle of flesh and glitter and cheerful, lipsticked grins in soft focus, on grainy 16mm film. It is beautiful, tasteful and tedious.

Its protagonist is aging cabaret performer Shelly, the de facto mother hen to bikini-clad spring chickens Mary-Anne (Brenda Song) and Jodie (Kiernan Shipka). Her relationship with her work is a romantic one; she watches Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes on her afternoons off and twirls around her living room. Hers is not a nudie show, she insists, but “the last descendant of Parisian Lido culture.” When it is announced that Le Razzle Dazzle will be closing, Shelly is shocked to discover that the world around her has moved on.

A feeling of wistful melancholy washes over the film, which serves as a lament for the passing of time. Shelly’s self-image remains frozen in the past, something that couldn’t be less true of the actress who plays her. Anderson shot to fame as a Playboy model in the 1990s. In recent years, she has redefined her image, campaigning for animal rights and striking up a high-profile friendship with WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. In 2023, she published a memoir, Love, Pamela, and was the subject of a (very good) documentary, Pamela, A Love Story. Over the last few years, she has stopped wearing make-up to red carpet events.

It’s a clever idea, to insert a former pin-up into a role that acknowledges the trap of fashioning a career from one’s sex appeal. Coppola refuses to condemn, punish, or mock Shelly for trading on her beauty. Instead, her anxiety about aging out of a job she’s been doing for decades is treated with solemnity. And why not? There are countless films about the existential crises of middle-aged men.

When asked her age at an audition, Shelly is reluctant: “36?” she offers. “Sorry, I lied, I’m 42,” she says, as Coppola frames Anderson’s 50-something face in close-up, her bejewelled baker boy hat sitting slightly askew. Shelly bats her false eyelashes. “Distance helps,” she adds, gesturing towards the cheap seats in the large, empty theatre. When her routine is dismissed and deemed unsexy, the movie offers her an opportunity to address her critics directly. “I’m 57, and I’m beautiful!” she shouts, with both anger and conviction.

Anderson brings her own vulnerability, exuberance and glamour to a scantily written role. As Shelly, she is bubbly and girlish, her optimism occasionally punctured by Anderson’s sharp awareness of her character’s flaws. The film is a vehicle for the actress’s specific gifts (and earned Anderson a Golden Globe nomination), but as written, the role is clichéd. A sub-plot involving Shelly’s strained relationship with her adult daughter Hannah (Billie Lourd) is explored through clunky dialogue leaden with exposition. Shelly explains that she was a single parent struggling to provide for her child. “You left me in the casino parking lot with a Game Boy!” Hannah replies, but Lourd’s flat delivery fails to conjure history or real hurt.

This is exactly the problem. Anderson’s performance is genuinely moving, but without narrative scaffolding, the film starts to fall apart. Set pieces, such as a scene where Jamie Lee Curtis performs a cathartic dance solo to “Total Eclipse of the Heart” on top of a casino table, feel disconnected from the wider story and devoid of deeper insight. Curtis plays Annette, a straight-talking cocktail waitress and one of Shelly’s friends; her scenes add texture, but not momentum.

Cinematographer Autumn Durald Arkapaw shoots much of the film with anamorphic camera lenses that create a distorted, blurred effect at the edge of the frame. The idea, presumably, is that the women at the centre will be in focus. It feels like a distracting choice. Coppola is enamored with how the film’s world of faded glamour looks, capturing Shelly in a series of slow-motion interludes. She poses in parking lots and pouts under neon lights. But Coppola’s pretty images are padding. They float by slowly, like feathers loosened from one of Shelly’s crowns. An 85-minute film surely shouldn’t feel like this much of a drag.

“The Last Showgirl” is in cinemas now

This article appears in the 26 Feb 2025 issue of the New Statesman, Britain in Trump’s World