In last year’s bustling pre-Christmas book market, one music title stood out. By a busy songwriter and performer about to enter his eighties, it contained essays, rare photographs, tender memorabilia, plus an introduction by the poet Paul Muldoon. Paul McCartney: The Lyrics was all about underlining the legacy of an artist in a specific way: one that was distinguished but generous, welcoming and relatable.

This year, another book looking back at the past arrives from an active, elderly legend, but its tenor is different. His book’s title is grander for starters: The Philosophy of Modern Song. The inside jacket boasts that it’s Bob Dylan’s first published work since winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016 (take that, McCartney), and his first book since his wild – and wildly successful – 2004 memoir, Chronicles: Volume One.

A book of Dylan’s ruminations on the recorded music of others, it resembles an “epic poem”, the press puff expands, full of “dreamlike riffs” that add “to the work’s transcendence”. But from this book’s cover onwards – the jacket is emblazoned with pulpy red lettering and a relaxed snap of Little Richard and Eddie Cochran standing next to the obscure rockabilly singer Alis Lesley, for no discernible reason – this is the work of a legend wanting to confuse people, to upturn the idea of relatable legacy completely.

When I started writing about music aged 25, Dylan seemed as intimidating to me as a Mount Rushmore sculpture. A great man who dominated the American popular music landscape (as well as the British monthly music magazine market), I presumed he had to be gazed at by us minions in awe. This set me against him. Time taught me to enjoy Dylan’s impishness instead, his capacity to shock.

I loved how he had deliberately made his 1970 album Self Portrait loose and messy to stop people mythologising his genius (I also love the glorious song that begins it, “All the Tired Horses”, on which he doesn’t sing). I still adore the festive two-finger protest of his 2009 album, Christmas in the Heart, and how its lead single, “Must Be Santa”, made the devotees rage, but still makes my heart sing every year.

Reading The Philosophy of Modern Song with the same spry approach makes it quite the romp – up to a point. It harks back to Dylan’s playful radio show Theme Time Radio Hour on XM Satellite Radio, which originally ran to 100 episodes from 2006 to 2009 (two standalone extras were released in 2015 and 2020, the latter to promote a whisky brand he’d just launched).

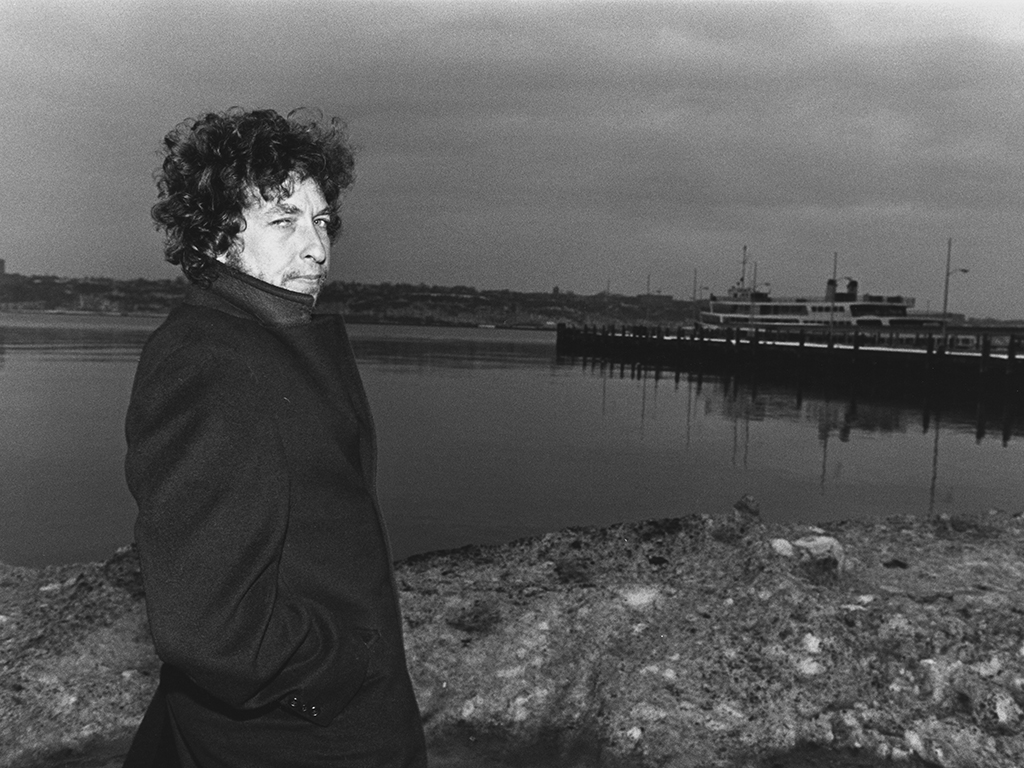

Its song choices were based around subjects like “Hair”, “Drinking” and “Death and Taxes”, and some of those lists get recycled, a little lazily, in these colourful pages. The show was also zhuzhed up by vintage radio jingles, readings from poetry, emails and letters. The equivalents here are old photographs (none of Dylan, but of the artists he features), magazine covers, film posters and small classified adverts, many of them promising to teach people piano or singing at rapid speed, a shortcut to soaking up the promise of rock and roll.

Trying to work out the significance of these images is half the fun, of course. I wonder if the harmonica advert around the first track in the book – a 1963 country single, “Detroit City”, sung by Bobby Bare – is a nod to the instrument with which Dylan was strongly associated around that same period, during his early years of fame. “Detroit City” is about a man who has failed to make his fortune in the big smoke, and his desperation to go home, although that world is also a fantasy. “The listener knows that [world] just doesn’t exist,” Dylan writes. “That’s why this song works.” This could have been Dylan’s lot. Instead, here we are.

[See also: The battle of the Dylanologists]

Dylan’s chapters often begin with passages of speedy, staccato ruminations addressed directly to the reader, before going on to more factual accounts of the chosen songs. It’s hard not to hear the ruminations in Dylan’s high-pitched, tremulous wheeze (I read the entry on Ricky Nelson’s cutesy 1958 ballad “Poor Little Fool” thusly (my italics and extra letters): “in the past you entertained yourself with other people’s heartssss, you stretched the ruuuuules”).

Many of these ruuuminayshuuuuuns would get most music magazine editors scrambling for the red pen. They rarely add anything new to the conversation, but they’re often campy fun. Their style also suits the fact that many songs in the book are mid 20th-century confections, packed with melodrama or high excitement. A few more surprising choices appear, but they’re not as extreme as when Dylan played LL Cool J’s “Mama Said Knock You Out” or Blondie’s “Heart of Glass” on Theme Time Radio Hour.

Songs by the Who, the Clash and Elvis Costello are among the most eye-widening selections. When Dylan writes that Costello’s group, the Attractions, were “the better band of all their contemporaries”, you wonder if he liked the idea of his successors swooning at the five-star review. He then reminds us why he might have chosen Costello’s song “Pump It Up” in the first place: it was inspired by Dylan’s delivery of his 1965 track “Subterranean Homesick Blues”.

Dylan’s writing is at its best when it’s funny. Debating the merits of wealth around Elvis Presley’s 1956 recording of “Money Honey”, he unleashes a zinger: “No matter how many chairs you have, you only have one ass.” When discussing the rock’n’roll tailor Nuta Kotlyarenko, who designed the rhinestone-covered Nudie suits beloved by country stars Porter Wagoner and Hank Williams, Dylan makes a comment that could refer to his transition from being born Robert Zimmerman to becoming Bob Dylan: “Like many men who reinvent themselves, details get dodgy in places.”

His passion can also be touching. On the magic of Perry Como’s single, “Without a Song”, he writes like a sweet, earnest teenager: “there is nothing small you can say about it”. On political songs like the Temptations’ “Ball of Confusion”, he’s full of praise for its writers, Barrett Strong and Norman Whitfield, who were great hit-makers for Motown Records. “Everything they wrote is meaningful and true to life… they saw it and told it relentlessly.”

But if we’re relying on Dylan to consistently offer clarity on these songs, we’re out of luck. Some of his entries feel dashed off or too short, even if they’re meant to leave us wanting more. Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti” is the sound of a preacher “sounding the alarm”, knowing “the world’s gonna fall apart”, but that’s about it. The entry for Ray Charles’s “I Got a Woman” is a brief whinge about relationships going sour, with no comment on the substance of the song itself, or its actual lyrics.

The biggest disappointment is the way Dylan’s book is utterly drenched in testosterone. (Its back cover image, a vintage photograph of earnest men in a record shop, should have been a warning.) Only four songs in this book of 66 are performed by women. Sonny Bono gets more attention than Cher in an entry on “Gypsys, Tramps & Thieves”. Judy Garland gets one word in a chapter that is ostensibly on her version of “Come Rain or Come Shine” (“razzmatazz”). Nina Simone gets some kudos for her “measured, defiant delivery” on “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood”, although the ambiguous opening lines of Albert Camus’s 1942 novel, L’Étranger – not a known influence on the lyric – warrant much longer analysis.

A list of great Detroit musicians solely comprises men, leaving out Aretha Franklin, Martha Reeves and Diana Ross. Much worse is how Dylan enjoys riffing on women being monstrous and doing poor men wrong. (He could argue this is because he’s only describing the songs that he chose, but, hey, he chose them.)

His entry on the Eagles’ “Witchy Woman” is particularly gut-churning. Dylan mourns “the woman with the world view – the progressive woman – youthful, whimsical, and grotesque”, and how “the lips of her cunt are a steel trap”. Discussing Johnny Taylor’s 1973 divorce song “Cheaper to Keep Her”, he decries “women’s lib lobbyists [taking] turns putting man back on his heels until he is pinned behind the eight ball dodging the shrapnel from the smashed glass ceiling”.

But before “the feminists chase him through the village with torches”, he says, by means of apology, women can commit polygamy too. “Have at it, ladies. There’s another glass ceiling for you to break.” His disdain feels palpable.

These are dark shadows in a book that holds light, amusing treasures, although not as many as the press puff would like you to believe. You wonder whether Dylan included these rants because he enjoys the idea of staying provocative – not for him is the smoothing-out of his life story to suit the whims of the Christmas book market.

But The Philosophy of Modern Song also reminds us that loving music isn’t about gazing upon artists indiscriminately, in jaw-sunken awe – which is something he agrees with, weirdly enough. “Knowing a singer’s life story doesn’t particularly help your understanding of a song,” he writes. “It’s what a song makes you feel about your own life that’s important.”

The Philosophy of Modern Song

by Bob Dylan

Simon & Schuster, 352pp, £35

Purchasing a book may earn the NS a commission from Bookshop.org, who support independent bookshops