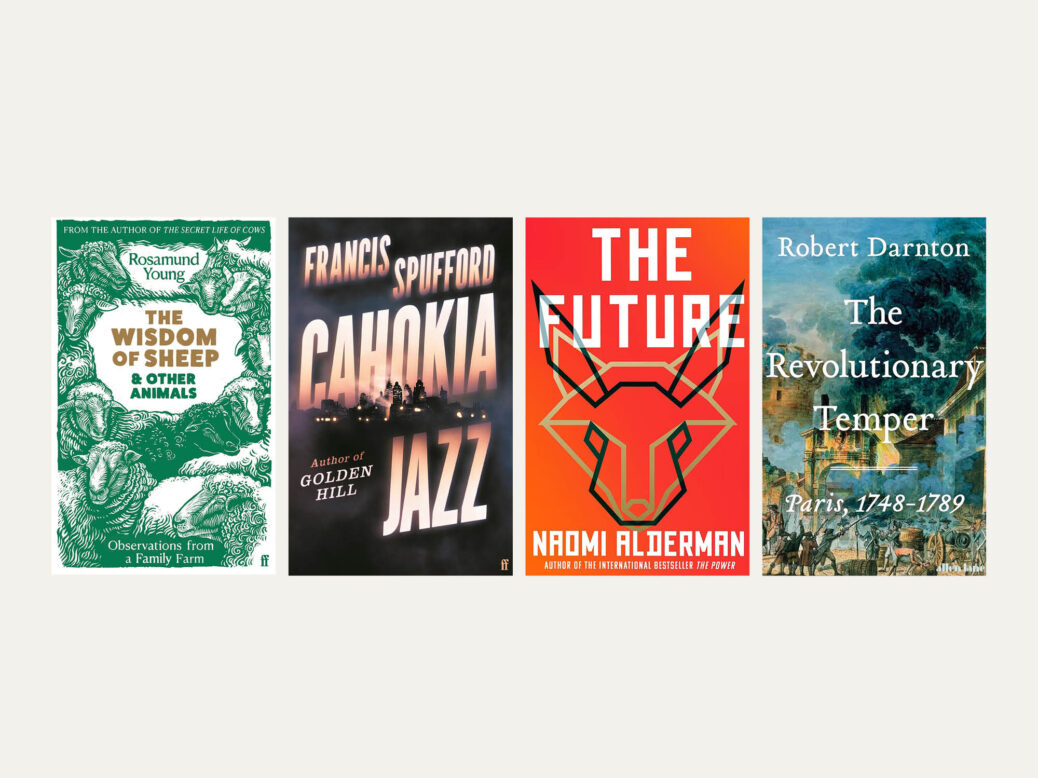

The Revolutionary Temper: Paris, 1748-1789 by Robert Darnton

Allen Lane, 576pp, £35

It was nearly 35 years ago that Simon Schama in Citizens looked beyond the big players of the French Revolution – Louis XVI, Robespierre, Danton et al – to examine the hopes and motivations of the sans-culottestoo, individually and en masse. In his similarly impressive and deeply learned history, Robert Darnton provides a precursor to Citizens. Schama’s book covered the first five years of revolution, to 1794, and Darnton looks at the period between 1748 and the storming of the Bastille in 1789. An astute observer, he concludes, could have seen that serious trouble was brewing long before it broke with such violence.

The second half of the 18th century was, he says, a vibrant information age and the citizens of Paris were presented with a running commentary on the events of the day, whether political or gossipy and scurrilous, not just through news-sheets but also via café talk, popular songs and plays. In them, as royalty and politicians were being mocked, the social order was shifting. Darnton’s command of sources is remarkable and the cumulative effect of the voices and collective currents he disinters is to make the revolution preordained.

By Michael Prodger

[See also: Why we chose Benjamin Myers’s Cuddy as the 2023 Goldsmiths Prize winner]

The Wisdom of Sheep and Other Animals by Rosamund Young

Faber & Faber, 272pp, £14.99

Kite’s Nest in the Cotswolds is a family farm whose definition of family is wide: included are a host of inquisitive and characterful animals. The farmer Rosamund Young, the author of the bestselling The Secret Life of Cows, features them all here. There’s the hen who “barged in” to the kitchen, laying her egg on Young’s freshly polished floor – despite being asked quite politely not to. And Tealeaf the sheep, who has a “good brain, and good powers of reasoning”, although she was initially reared by a ewe whose teats didn’t produce milk properly, which led to her spending some time without a full feed.

The book is a collection of scribbled diary entries, more formal memoir, and poems – Young’s own, as well as others from popular literature, such as an extract from John Clare’s The Shepherd’s Calendar. The author discusses her own rewilding and organic farming methods, as well as the outbreak of mad cow disease in previous decades, but avoids politicising these as environmental concerns. Exactly what “wisdom” sheep offer us is unclear – but Young’s love of her profession and the creatures who depend on it is unmistakable.

By Megan Kenyon

[See also: Inside the mind of Hilary Mantel]

The Future by Naomi Alderman

4th Estate, 416pp, £20

In 2017 Naomi Alderman read a New Yorker article about the growing interest in survivalism among Silicon Valley executives. The super-rich – with a toxic mix of extensive wealth, inflated egos and plenty of real-world disasters to fear – were preparing for an imagined doomsday by building bunkers and undergoing eye surgery to achieve perfect vision (presumably so they could make a quick escape without worrying about finding their glasses). In her latest novel, Alderman wryly challenges this culture of individualism with her customary satire. She follows three tech billionaires who, after successfully monetising the world’s data, are now transfixed on owning technology that predicts disasters. Yet in seeking to control the future, the trio fail to remember that one simply can’t.

Seven years ago Alderman received international acclaim for The Power, which envisioned a world transformed when women developed a physical advantage over men. In her new work she skilfully confronts the faint divide between self-protection and narcissism – and raises compelling questions about the morality of consequentialism.

By Christiana Bishop

Cahokia Jazz by Francis Spufford

Faber & Faber, 496pp, £20

Francis Spufford’s third novel is a vibrant thriller set in an alternative history. Cahokia, across the Mississippi River from present-day St Louis, was once the site of a Native American city. In Spufford’s telling, it’s the 1920s and the metropolis still has a thriving native population. The city’s common language is the indigenous Anopa, and a word in this tongue is written in blood on the forehead of a man found dead on a rooftop. Phineas Drummond and Joe Barrow are the police officers tasked with the case. How and who language includes and excludes will be a crucial part of this story, from those who refuse to “dirty their mouth with the invader’s language”, to Barrow, who is Native American but does not speak Anopa – to his constant embarrassment.

Spufford, a professor of creative writing at Goldsmiths, University of London, is the author of two critically acclaimed novels that query or subvert the facts of history: Golden Hill (2016) and Light Perpetual (2021). This time his conceit is ever more ambitious and consequential. Spufford’s prose is energetic and rhythmic, yet his theme – namely racial politics in the US today – couldn’t be weightier.

By Ellen Peirson-Hagger

[See also: How the Barclay brothers built and wrecked an empire]

This article appears in the 25 Oct 2023 issue of the New Statesman, Fog of War