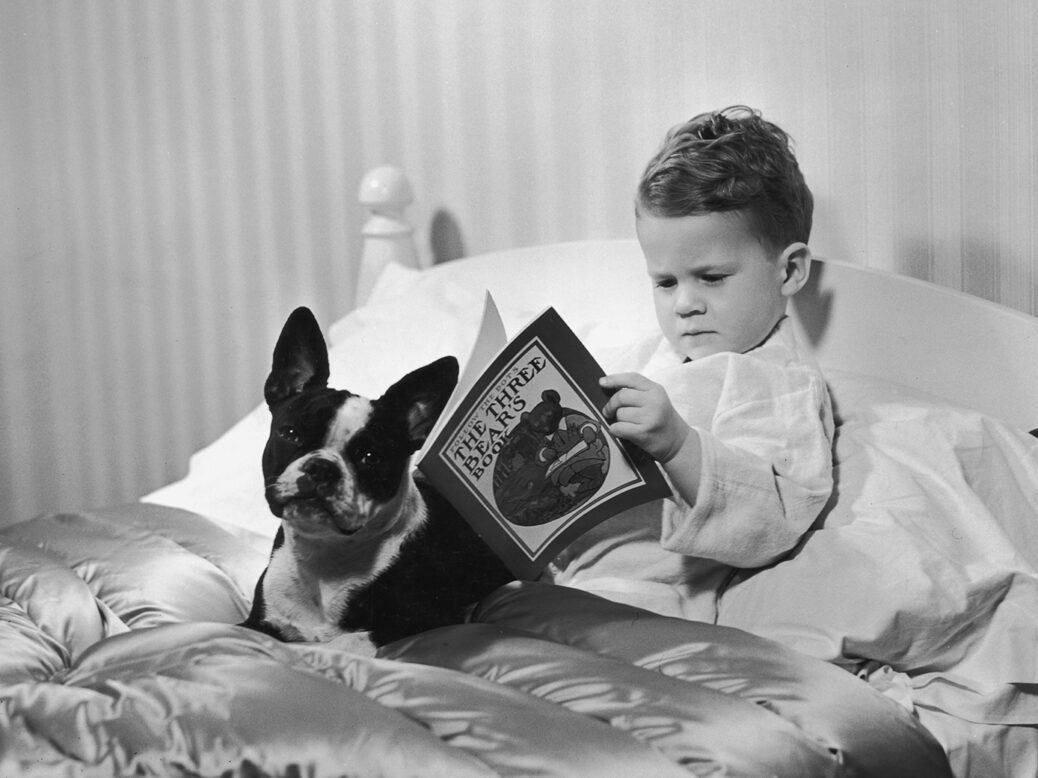

I Want My Hat Back by Jon Klassen is currently at the top of my one-year-old son’s pile of bedtime stories. I want to say that it’s his favourite, but in all honesty it’s impossible to tell, since he adopts the same baffled expression throughout the reading process, regardless of which book we choose. All I can say with any confidence is that I Want My Hat Back usually holds his attention. He seems to like it slightly more than the copy of Quantum Physics for Babies that my husband keeps forcing on him. But he seems to like it slightly less than an empty cardboard box.

And yet all the adults love I Want My Hat Back, including me. In fact, it’s “the funniest book ever written” according to one reviewer. A brief synopsis: there’s a bear, and he’s trying to find his lost hat. He asks the other animals if they’ve seen it and they all say no. But one of them is lying. The foolish bear doesn’t notice that the deceitful rabbit is wearing the stolen hat. Until, suddenly, he does. In the book’s slightly shocking finale, the bear retrieves his hat and eats the rabbit.

So our protagonist is guilty not only of murder, but of disposing of a corpse with intent to obstruct a coroner’s inquest. He may also have committed robbery, given that his hat is reacquired only through force. “This book has a terrible message” reads one of the (rare) one-star reviews on Amazon. It’s hard to disagree.

But so what? I Want My Hat Back is funny and silly and doesn’t actually defy the moral strictures typically imposed on 21st-century children’s fiction. Modern protagonists are allowed to be extremely naughty, sometimes even criminal. Our library includes tales of unruly dogs ruining picnics, ill-mannered tigers inveigling their way into homes, and moles who go around pooping on other characters’ heads.

Beatrix Potter’s disobedient characters always got their comeuppance: think of Peter Rabbit trapped in chicken wire, or Tom Kitten wrapped up in pastry. Her Edwardian readers would have been left in no doubt about the perils of naughtiness. Go back a little further, though, and the moral message in children’s books is even more foreign. Mary Martha Sherwood was a contemporary of Jane Austen’s and one of the most successful children’s authors of her day. But her books are now almost unreadable.

Sherwood’s History of The Fairchild Family, for instance – a bestselling series published between 1818 and 1847 – follows children Emily, Lucy and Henry as they discover their original sin and consequent need for redemption. This combination of sentimentality and preachiness is dialled up further in Sherwood’s colonial novels, featuring pious little English children who convert their Indian servants to Christianity and then die in a very tragic and beautiful manner.

I do wonder if there were some 19th-century parents who couldn’t quite stomach Sherwood’s books, just as there are 21st-century parents who avoid our modern moralising genres. Our local (and very lovely) children’s bookshop has a section devoted to race and gender. The most successful book on these shelves is Ibram X Kendi’s Antiracist Baby, which promises to provide “the language necessary to begin critical conversations at the earliest age… the perfect gift for readers of all ages dedicated to forming a just society” (you see, original sin remains a prominent theme in the literature we give to our children, even if we don’t describe it as such).

The moral message hasn’t disappeared from children’s books, but the content of the message has subtly changed. In the past it was more likely to emphasise the virtue of obedience, today it most values the virtue of inclusion.

I Want My Hat Back is a fun read, in part because it foregoes the heavy-handed moralising of so much children’s literature, past and present. Our bear may be a robber and a murderer, but we can forgive him those sins. Does my one-year-old son have any idea of the book’s “terrible message”? I would ask him, but he’s rather busy with his cardboard box.

[See also: In Mike Nichols’s inspiring life, I find a brief, defiant distraction from war]

This article appears in the 18 May 2022 issue of the New Statesman, Putin vs Nato