It’s hard to get away from the conclusion,” Gavin Francis writes in his wise and thoughtful book Recovery: The Lost Art of Convalescence, “that in the rush to modern medicine we’ve lost something important.” Francis is a GP, and he makes this comment when he tells us that he can no longer arrange for a frail and elderly patient to be admitted to hospital simply for much needed nursing care and convalescence. Instead, there must be a proper medical diagnosis and a plan to get the patient out of hospital as quickly as possible. Convalescence and recovery don’t count. Indeed, as he points out, these words are generally absent from the indices of medical textbooks. Yet common sense and experience tell us that they are a vital part of illness, and this truth has become blindingly obvious with Covid and its long-term complications. Illness is not a binary experience where you are either ill or well. You have to recover, and that takes time, and is often a far from simple process.

A sense of loss pervades much of the book, which starts by describing Francis’s own childhood experience of illness and recovery – once with meningitis and once with a badly fractured knee. He remembers lying in a hospital room with “large windows that gave on to trees and afternoon sunshine”. He remembers how long it took to regain the use of his leg and to recover from the profound fatigue that followed the meningitis. When he was training as a doctor years later in Edinburgh, he had the good fortune to work in two hospitals that had been originally established as convalescent hospitals, and which embodied all the principles of access to fresh air and light which Florence Nightingale had emphasised in the 19th century. I had exactly the same experience myself of training and working in what had once been a convalescent hospital. The tall windows, the gardens and the sense of community were a real joy, appreciated by both staff and patients, and in profound contrast to the huge and soulless modern hospitals where most medicine is now conducted. There are few, if any, of the convalescent institutions left – they have all been sold and turned into gated, high-end residential estates.

Although Nightingale believed in the mistaken miasmatic theory of illness – that infections were spread by foul air – and was almost certainly a dualist, believing that mind and matter were separate entities, she was remarkably prescient. In her Notes on Nursing, published in 1859, she wrote:

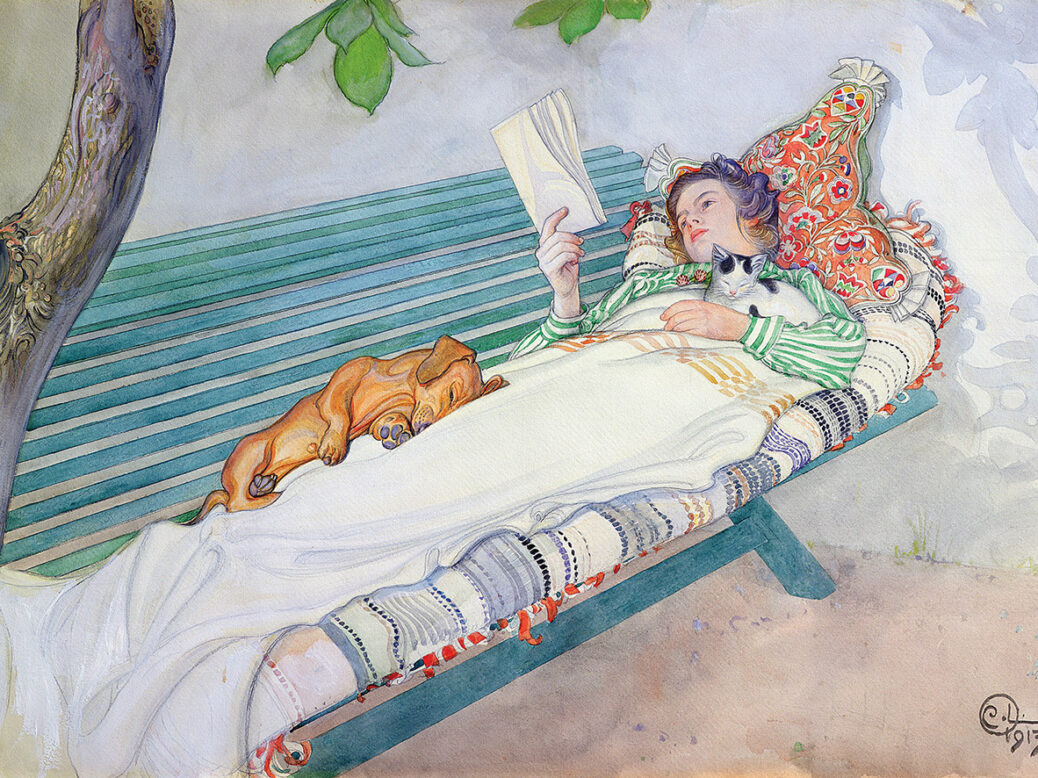

Little as we know about the way in which we are affected by form, colour, by light, we do know this, that they have a physical effect. Variety of form and brilliancy of colour in the objects presented to patients are actual means of recovery.

It is now well known that mind and matter are not separate entities. Our immune systems, for instance, have complex connections to our brains – admittedly, poorly understood – and states of mind can have a profound effect on “physical” illness, just as “mental” illness can have profound effects on the body. And yet this knowledge has been largely neglected in healthcare in recent decades. You only have to look at the number of expensive NHS hospitals built under the Private Finance Initiative, which have an uncanny resemblance to shopping malls and airports, to appreciate this truth. The last thing you get in a modern hospital is peace or quiet. As Francis observes, hospices are the exception. Only when we are dying, it would seem, are we allowed to rest and have contact with nature again.

Francis writes that the medicine in which he was trained assumes that once the crisis of illness has passed, the body and mind find ways of healing themselves. As a GP who has observed thousands of patients struggling to recover from illness, he knows this isn’t true. Recovery, he argues, needs time and guidance. I suspect that he is the kind of GP most of us long for. He sees his role as a “guide in the landscape of illness” and not as a mere prescriber of pills.

Medicine, he writes – and I agree passionately – is above all about the relief of suffering, and not simply the prolongation of life and the treatment of illness. Listening to patients and learning from them is a crucial part of this. But Francis also points out that there are many different kinds of doctors and patients. Some will suit each other, and some will not. As I know from my own experience, the occasional (and painful) breakdown of trust – a quality that is vital for all medical encounters – is inevitable.

As recovery requires time, Francis writes of the importance of telling patients to allow themselves this luxury, without guilt, and that they should not feel they are malingering. “Self-compassion,” he writes, “is a much-underrated virtue.” Even the small number of deliberate malingerers (according to Francis, government statistics show that only 1.7 per cent of sickness benefit claims are fraudulent, despite what the tabloid press might claim) suffer from self-reproach.

The great 19th-century German doctor Rudolf Virchow – a giant of modern medicine – wrote that doctors are “the natural attorneys for the poor”. Francis describes how for so many of his patients, recovery – and he correctly makes no distinction between physical and mental illness – is inextricably tangled up with their work. The pressure to be ever more productive and the inequality that disfigures our society have a real impact on people’s health. This has been known for many years, especially from Michael Marmot’s work showing that life expectancy is closely correlated to your position on the social ladder. In his own GP surgery, Francis and his partners have sensibly agreed that they should each have a three-month sabbatical every few years. I remember very clearly when I was still working full-time, I could always tell when my colleagues had been away on holiday – their eyes and faces were so much brighter. John Maynard Keynes’ famous essay “The Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren”, written 94 years ago, in which he envisioned a future where we would only work three hours a day and could devote ourselves to leisure, seems charmingly quaint.

Recovery is not always complete. With some illnesses, it is a question of coming to terms with loss, and that you will never return to what you had, or were, in the past. Here, guidance from a sympathetic therapist, Francis tells us, is essential. And yet, as he also explains, we are all so suggestible, so shaped by our expectations, that the guide must take great care in how he or she describes the landscape of any particular illness to the patient. The nocebo effect – that we can make ourselves ill by expecting to be ill – is just as powerful as the placebo effect, which works in the opposite direction. I can think of many patients whose lives had been damaged by some casual, thoughtless comment from a colleague. As a patient myself now with advanced prostate cancer, and despite being a doctor, I was surprised at how I clung to every word or phrase from the doctors I saw, looking for significance that probably wasn’t there. And I wonder how often I might have got it wrong when speaking to my own patients in the past.

This book is a practical guide to recovery from illness as well as a meditation on the practice of medicine. Take a holiday, says Francis, travel if you can, read books, set yourself achievable goals, don’t compare yourself to others, allow yourself time, commune with green, living things, have a pet.

I cannot think of anybody – patient or doctor – who will not be helped by reading this short and profound book.

Henry Marsh’s next book, “And Finally”, will be published in September by Jonathan Cape

Recovery: The Lost Art of Convalescence

Gavin Francis

Profile, 144pp, £4.99

Purchasing a book may earn the NS a commission from Bookshop.org, who support independent bookshops

This article appears in the 12 Jan 2022 issue of the New Statesman, The age of economic rage