The 1960s and 1970s brought a stream of satisfying scandals. Lord and Lady Docker; John Profumo; Lord Lucan; Jeremy Thorpe – all of these “affairs”, and more, provided something that, at the time, this democracy seemed to need for its psychological well-being.

They reassured voters, battered and disconcerted by national decline, that their misfortune had come about because the people at the top were all fundamentally rotten. The vivid detail of the scandals provided an endless supply of satire. Innumerable cartoonists were kept gainfully employed. Private Eye rose in reputation on the back of these affairs. And, of course, they sold a lot of newspapers in the golden age of the popular press. Each twist of each story bumped up the sales of the Express, Mirror and other titles.

But was it really a golden age? This defence of John Stonehouse – the former Labour minister who disappeared off a Miami beach in November 1974, leaving only a pile of his clothes behind him on the sand, before being apprehended in Australia living under a different name, and finally ending up in a British prison – asks us to think again.

The press, argues Julia Stonehouse, was wildly unreliable, frequently malicious and generally in cahoots with the police and state actors. She believes her father was grievously mistreated. Falsely rumoured to be a Czech communist agent, he was the victim of an unfair trial and suffered heart attacks in prison, untreated, while his reputation was torn apart.

[See also: Glenn Greenwald: the greatest journalist of all time?]

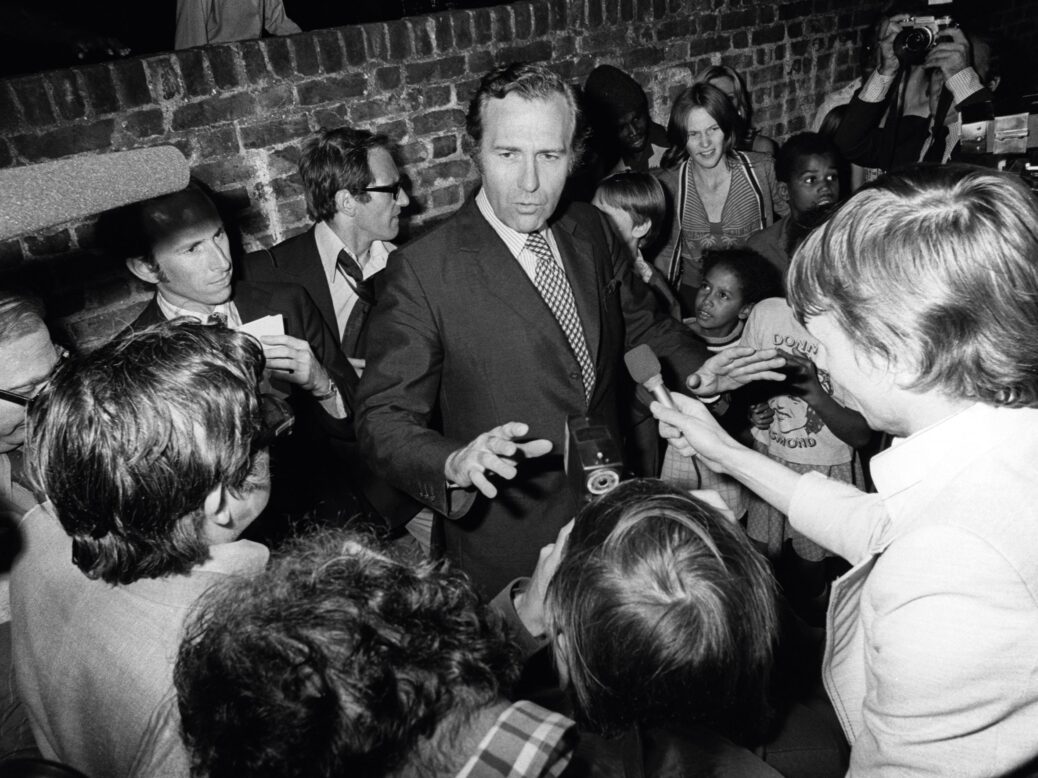

A former postmaster general and technology and aviation minister, Stonehouse had been a rising star in the first Harold Wilson government – impossibly good-looking, charismatic, hugely energetic.

His disappearance, in the middle of a political crisis, was dissected in cabinet, investigated by the secret services here and in Washington, DC, and provoked a global news story. For months, speculation about the truth – why had he faked his own death? What was really going on? – swirled through every saloon bar and breakfast conversation in the country.

The cartoonists and writing satirists had a high old time dancing on him. But, it seems, nothing about this story was funny.

The author’s argument, which follows Stonehouse’s own autobiography, is that her father had suffered a major mental breakdown, caused in part by political disillusionment and in part by press persecution. Ashamed of himself, he tried to erase his identity by staging his suicide and so destroying “Stonehouse” the public figure. He did this in order to live quietly, harmlessly and anonymously as another man. Yes, it was a mad idea, but the MP had long been self-medicating on Mandrax and Mogadon in dangerous quantities. Desperate and hounded, he ran away.

To defend her father, Julia Stonehouse has had to dig into his convoluted business dealings with Bangladesh, and his cascade of export companies, which led to fraud, conspiracy and theft charges; and to pick through the now-released files of the Czech intelligence service, trying to demonstrate that he was simply being used by lying agents and was never a traitor. To me, she is broadly convincing, although the detail required to make her case will wear down some readers.

[See also: The misrepresenting of Monica Jones]

Where she cannot defend her father is where she herself knows most about the effects of what he did – that is, in the cruelty inflicted on his own family by his apparent suicide, and his long affair with his secretary, Sheila Buckley, whom he later married. When he vanished into the ocean – in fact, swimming back to pick up dry clothes, money and a fake passport in the name of a dead constituent, before flying in a ridiculously criss-crossing way to Australia – his wife and children had to read suggestions that he had been eaten by sharks, or been spirited away by a Russian submarine to Cuba, or been encased in concrete and drowned by the mafia. With journalists banging on the door and following their every move, they were devastated and disorientated.

There is a jaw-dropping account of the small hours of Christmas Day, 1974, little over a month after his apparent suicide, when his family, exhausted after talking about him and wrapping presents, were sitting in his study. The phone rang, with journalists claiming he had been discovered in Australia. At 4am, the phone rang again – it was a quavering Stonehouse, calling from a Melbourne police station to apologise. Barbara, his wife, who later divorced him, flew over immediately, with journalists, to help. She comes across as a person of extraordinary grit, loyalty and political nous.

Julia Stonehouse has to refute the argument, much heard at the time, that his disappearance – rather than being caused by a mental breakdown – was a cynically prepared plot made with his mistress Sheila, using other people’s money. Again, she has to pick through the fine detail of allegations about underwear, suitcases and trysts in Copenhagen, during which her relentless if understandable attacks on the British media become exhaustingly repetitive.

***

This is, above all, a story of its time. With its humourless policeman, bungling communist agents, hideous prisons, manically competitive tabloid hacks and failing politicians, it is as much a period piece as Harold Wilson’s “Lavender List” or the first publication of the Murdoch Sun. Such a disappearance would be simply impossible in the internet-connected world, with airport and social media surveillance. Stonehouse’s desperate measures of inter-company borrowing to keep his firms alive recall, on a much smaller level, what Robert Maxwell got up to. The aggressive direction of the judge to the jury in his case, which later led to a change in the law, recalls nothing so much as Peter Cook in a wig. The hysteria about national decline and the paranoia about communist spies, fed by ex-MI5 right-wingers in business and the media, remind us that not everything now is worse than in the good old days.

In many ways, Stonehouse is a symbolic figure of that period – the manic anti-hero of his own picaresque novel. An RAF pilot who just missed the Second World War and trained as an economist, he came from a Labour and Cooperative family and started out as an idealistic campaigner: a fervent supporter of the Movement for Colonial Freedom, he visited Africa and Bangladesh, and hosted liberation leaders in his house.

But as a Labour MP, he became increasingly frustrated by trade union truculence, moving firmly to the right of the party. Believing, like many others, that the only escape from national decline was more effective exporting, he set up his own companies – which only increased suspicion of him inside the party. When he was eventually expelled from Labour, he joined the English National Party, a largely forgotten collection of eccentrics enthused about an English parliament and Morris dancing, with no connection to the later extreme organisation of a similar name.

[See also: When red walls come tumbling down]

By then, there was no politics left for St. Liberation movements abroad had turned corrupt or authoritarian; Labour MPs had turned their backs on this charismatic capitalist. Wilson, facing his own troubles as a rumoured Soviet agent, could not afford to help in any way. The right, either believing Stonehouse was a commie collaborator, or simply exploiting the rumours to attack Wilson, equally abhorred him.

Journalists, with a few honourable exceptions, couldn’t resist the lure of a glorious front-page story and twisted many of the few reliable facts they had. Many people in public life have paused, at some point, and wished they could start all over again. But it takes a particular level of stress to want to cancel yourself. Apart from the crisped and purling surf on that breezy afternoon in Miami, and the vague dream of a new life in Australia, John Stonehouse felt there was nowhere left for him to go, nothing left for him to say. A morality tale, and a sad one.

John Stonehouse, My Father

Julia Stonehouse

Icon Books, 416pp, £16.99

This article appears in the 25 Aug 2021 issue of the New Statesman, The Retreat