Written on the monument to Kant in Kaliningrad (once Königsberg) are the final words of his Critique of Practical Reason. Only two things, he wrote, filled his mind with ever-increasing awe – the starry heavens above him and the moral law within him. In the equally awe-inspiring book Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst, Robert Sapolsky, a neurobiologist at Stanford, endocrinologist and expert on baboons, sets out to ground morality in neurobiology as opposed to the pure reason of Kant’s “categorical imperative”. But unlike Kant (at least for me), Sapolsky is highly readable. Behave is a tour de force of science writing for the general public – scholarly and all-encompassing, lucid, profound but light-hearted and with very funny footnotes and learned endnotes. You do not often read a book of almost 800 pages on such a serious subject with so much enjoyment.

Sapolsky presents his analysis in reverse-chronological order. The first chapters describe the immediate neurological processes in our brains that generate behaviour. He is concerned not with the (relatively) simple mechanisms of perception and movement but with the parts of the brain – in essence, the frontal and inner temporal lobes – where cognition (thinking) and feeling take place. The book goes backwards in time from the immediate action of the nerve cells that generated a behaviour to the hormonal, genetic and environmental influences that resulted in the brain cells firing in the way they did. So the book starts with hard neuroscience and moves through endocrinology and genetics to psychology, anthropology, history and evolutionary biology. Sapolsky deals with each of these with great clarity, always stressing the variability and complexity of the experimental results he describes. He writes that if his book has an underlying theme, it is: “It’s complicated.” He is a determinist but not a simple one.

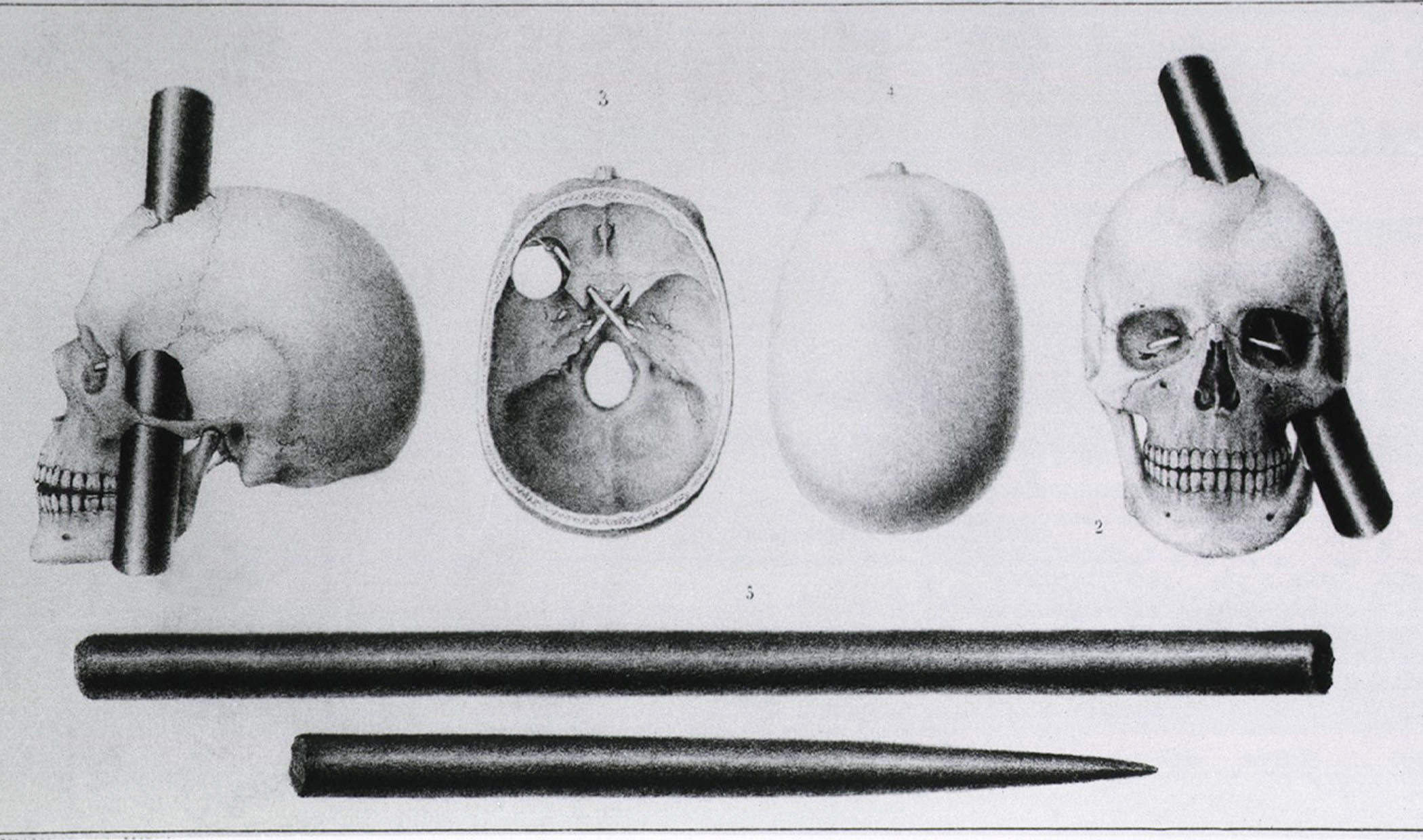

Until only a few decades ago, the frontal lobes of the brain were seen as a black box. We knew that people with damage to the frontal lobes suffered personality change. We knew that a very high proportion of people in prison for violent offences had a history of head injury earlier in their lives. In the 19th century, doctors learned of Phineas Gage, the unfortunate Irish-American railway worker who, in 1848, had a tamping iron blasted through his skull in an explosion. Gage suffered a major personality change for the worse and was condemned to be mentioned in all popular neuroscience lectures and books ever since. You can see his skull at Harvard Medical School’s Warren Anatomical Museum.

Sapolsky describes the ever-increasing body of research in recent decades, much of it using functional brain scanning, which shows the way that different areas of the frontal lobes interact with the emotional areas of the brain known as the limbic system, and how these interactions are structured by our genes and experiences. Neuroscience tells us that reason and emotion are not separate processes in the brain but are deeply intertwined. How can you ever act if you have no motivation? A simple geography of thought and feeling in the brain does not always tell us very much (and functional brain scanning is not as accurate as it might appear), just as a map of a city gives only limited insight into its citizens’ lives. But it can sometimes be illuminating.

An example is Capgras syndrome – a condition in which people become convinced that their family and friends are impostors. The syndrome is probably best understood as arising from the anatomical disconnection of the facial recognition areas in the brain from the emotional areas. Just as the brain wallpapers over the blind spot in each eye, people with Capgras syndrome find a “rational” explanation for why they can recognise people but feel nothing for them.

Brain scans of children in Romanian orphanages who suffered appalling emotional and physical deprivation have shown not only that they have smaller brains with less frontal metabolism and connectivity than children brought up in normal families, but that they have larger amygdala, the parts of the temporal lobes involved in fear and aggression.

Sapolsky uses the analogy of a car with faulty brakes to describe antisocial human behaviour. A mechanic will not accuse the car of being evil but instead will explain its bad behaviour in terms of its malfunctioning parts. Human behaviour is no different – it is determined by the mechanics of our brains. The difference is that we understand very little about them and so we invoke the mythical concept of a controlling self (which Sapolsky describes as a homunculus) located somewhere in our heads. Concepts such as “evil”, he argues, have no place in the modern world of scientific explanation. If people behave badly, it is because of the neurological, genetic, hormonal and environmental determinants that shaped their brains, not because of any evil nature. He concedes that punishment may be necessary as a deterrent but is adamant that it should not be seen as a virtue. In short, Sapolsky does not believe in “free will”. Yet he admits, “I can’t really imagine how to live your life as if there is no free will.”

Philosophers have spilled oceans of ink on the problem of free will. I find it impossible to disagree with Sapolsky’s conclusions, but I also find it impossible to deny the difficulty I sometimes experience when I have to make a decision. I accept that I do not choose my feelings and that they were formed by my genes and experiences in early life, but I can’t help but wonder why making choices can be so painful if it is all predetermined. Why did evolution invent conscious experience and pain if we are machines, in principle no different from cars?

Sapolsky invokes the part of the frontal lobes called the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) as an area that helps us “do the harder thing which is right”. It is part of the brain that matures in late adolescence and early adulthood and is largely shaped by experience. Sapolsky describes how it modulates our emotions and can be responsible for “better” behaviour, but in the process he comes perilously close to recreating the homunculus that he is so anxious to banish. Is my conscious self a mere echo of the way that my DLPFC has modulated my limbic system? That together they made the decision and not I? Yet I am my brain, including its DLPFC and limbic system. Language starts to break down at this point – at least, it does in my hands – and the philosophers had better take over.

This is the best scientific book written for non-specialists that I have ever read. You will learn more about human nature than in any other book I can think of, and you will be inspired, even if you find some of it hard to accept. Sapolsky – a massively bearded, pig-tailed, self-confessed Birkenstock-wearing neo-hippy Californian liberal and lapsed Orthodox Jew and, by his own account, a depressive teetotaler – comes across as a man of tremendous erudition and enthusiasm, deep wisdom and great humanity. To use the adjective he frequently employs to describe an exciting piece of scientific research, this is a cool book. Read it!

Henry Marsh’s latest book, “Admissions: A Life in Brain Surgery”, is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson

Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst

Robert Sapolsky

Bodley Head, 790pp, £25

This article appears in the 18 Oct 2017 issue of the New Statesman, Russia’s century of revolutions