The luminous histories of photography and astronomy have been intertwined at least since 1839 when Louis Daguerre photographed a crescent, and then JW Draper the full moon the following year. A decade later the first star to be imprinted on to polished silver photographic plate was Vega, in the Lyra constellation, charted originally by Ptolemy in the 2nd century. The ancient impulse to observe the heavens, to glean divine knowledge, certainty, or truth, has largely been in the gift of men – decorated philosophers, scientists and astronomers – to share with the world.

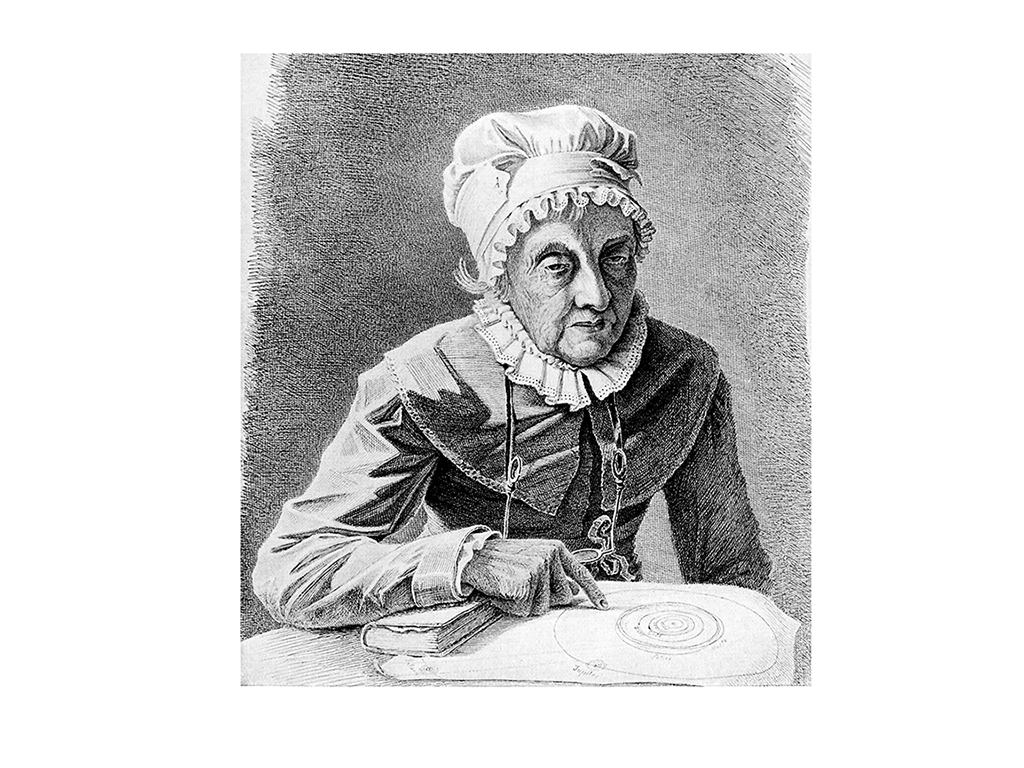

Caroline Herschel, in homage to whom the photographic artist Lynda Laird has created An Imperfect Account of a Comet, discovered eight comets and 14 nebulae in her lifetime, and became the first woman in England to receive a royal pension for her scientific work. These world-class discoveries were achieved despite the patriarchal constraints of the world she inhabited. Working as amanuensis for much of her career to her famous brother William, who became Royal Astronomer to George II in 1782, Caroline only narrowly escaped a life of domestic servitude. A childhood attack of typhus affected her vision, her growth and thus people’s perceptions of her abilities. The Herschels were a highly musical family and, when Caroline followed her brother from their native Hanover to England, she trained diligently to become the principal singer at William’s concerts, preferring to sing for him above all other conductors. As William’s obsession with astronomy grew he started to build his own telescopes and reflectors, the largest of which enabled identification of a new planet, now known to us as Uranus, as the seventh planet of the solar system, and which enshrined his legacy.

Among the principal areas of research undertaken by both Caroline and William Herschel was that of “double stars”, useful as a way of measuring stellar distance. While such stars are often bound by mutual gravitational attraction, one generally shines more brightly than the other – whether the siblings recognised their own relationship reflected back at them in these stars was not recorded for posterity. As modest Caroline pursued her discoveries, she would write to men of science, employing the most apologetic utterances: “Sir, I am very unwilling to trouble you with incomplete observations…” or “Dear Sir, I am almost ashamed to write to you…” and “Sir, In consequence of the friendship which I know to exist between you and my Brother, I venture to trouble you in his absence with the following imperfect account of a comet.” Caroline Herschel would hardly be the first woman in history to attempt to hide her radiant light under a bushel of regret and diffidence.

Nonetheless, her painstaking work revising the astronomer John Flamsteed’s authoritative catalogue of stars (the Historia Coelestis Britannica), recalculating and correcting data on some 3,000 stars, was eventually published by the Royal Society in full. As her brother’s health declined, she continued to collaborate in the research of his son, her nephew John Herschel, whose many contributions to observing the world include the coinage of the word “photography”, the use of chemicals to “fix” an image, and the invention of the cyanotype. A gifted polymath, he continued his astronomical work, enabled by another fastidious act of cataloguing by Caroline, which led to the first iteration of the astronomy bible, the New General Catalogue of Nebulae and Clusters of Stars, which is still in use today.

Laird’s homage to Caroline Herschel, which arose from her residency at the Royal Astronomical Society during its bicentenary in 2020, is borne of a similarly assiduous spirit. Using coordinates from Caroline Herschel’s records from 1790 in the Royal Astronomical Society archives, Laird relocated 560 stars that Herschel discovered were missing from Flamsteed’s account using astronomical software, with the aid of a contemporary calculation to account for the fact that their positions have moved between then and now, thus shining 21st century light onto Herschel’s celestial discoveries.

This resulted in Laird being able to input the contemporary star names into sky survey software, save the image, reverse it and print onto an acetate to make a photographic negative. Finally, she printed each star field onto a glass plate, echoing the original form of astrophotographic capture. As part of the commemorations of the bicentenary of William Herschel’s death, the glass plates will be displayed on bespoke light boxes as part of a live performance and installation on the 28th and 29th October in St Mary’s Church, Slough, which backs on to the home where the Herschels conducted their research. In keeping with the music that sustained the family, the installation is accompanied by a sound composition, 8 Comets, by Annie Needham and Phil Tomsett, structured according to the charted orbits of Caroline Herschel’s discoveries.

Laird is in illustrious company in her desire to commemorate Caroline Herschel through the visual arts. The astronomer is memorialised in a seat at an iconic table: Judy Chicago’s seminal feminist artwork, The Dinner Party. Each of the 39 plates and place settings are created to honour pioneering women from history, with the repeated vulva-butterfly motif in the Herschel plate created in the shape of an observant eye. The corresponding table runner is decorated with an embroidered letter C, which entwines itself around a gleaming telescope, as well as clouds, comets and celestial wonders. Herschel dines with Hypatia of Alexandria, who lived in the late fourth and early fifth centuries and was one of the first known female mathematicians and astronomers, and other visionaries such as Sojourner Truth, Virginia Woolf and Georgia O’Keeffe.

Though relentless transformation of the skies in the last century has forced us to radically reappraise our brave, o’erhanging firmament in terms of surveillance, satellites, space colonisation, air travel, drone strikes, air pollution and myriad other invisible topologies of space, the idea that we are all touched by starlight endures. When we gaze at the heavens, we are always looking back into to the past, into light once emitted, and in such moments, the delayed rays of the stars remind us that however small or great our achievements, we are all time travellers, briefly passing through.

Lynda Laird is artist in residence at the Royal Astronomical Society and assistant picture editor at the New Statesman. “An Imperfect Account of a Comet” is at St Mary’s Church, Slough, on 28 and 29 October, then moves to the Jodrell Bank Centre for Engagement at the University of Manchester.

[See also: Margaret Atwood: Why I write dystopias]