In 1967, Michael Ayrton published The Maze Maker, an “autobiographical” novel recounting the life of Daedalus – the creator of King Minos’ labyrinth and the inventor of the wings with which Icarus fatefully flew too close to the gods and the sun. Ayrton said the book had been “dictated” to him by Daedalus and it went on to receive critical acclaim. What underlay the story was a celebration of the mythological figure’s multifarious genius: Daedalus (meaning “skilfully wrought”) was the original artist-craftsman-inventor.

It is not hard to see why Ayrton was so drawn to him: he was himself a similarly protean figure who, during his short life (1921-1975), was not just a novelist but a painter, sculptor, print-maker, art critic, art historian, stage designer, book illustrator, broadcaster, film-maker and public intellectual. He refused to take any one of them as a label, however, calling himself simply an “image maker”. Indeed, he didn’t always know what form the image he was making would take: “There are times when one’s drawings, coming out from the paper, insist on becoming sculpture, at the next stage, rather than painting,” he said.

[See also: Livia Drusilla’s feast for the eyes]

Ayrton’s intellectual and artistic breadth did his reputation no favours: could a man of such varied accomplishments really be anything more than an upper-echelon Jack of all trades? He suffered in person too, writing that: “My intellect tears every emotion I have to tatters… I am left with a sort of sardonic husk.”

Critics were also more than a little bemused by his art. His work menaces – whatever he painted, drew or sculpted took on a slightly sinister edge; natural forms twist, human ones verge towards the primal, mythological ones are rapt with inner conflict. His most consistent theme, to the point of obsession, was the Minotaur and although commentators sensed the power of his pictures and sculptures of the beast, and recognised it as a concentration of urges, they couldn’t understand fully what the creature meant to him.

Ayrton seems to have believed that if the old myths were not real historical narratives they were nonetheless absolutely necessary. “We live by myths”, he once wrote, and he found them to be “lies no less true to me than facts”. Consequently, he saw his art as a quest “to understand what is further back than anyone is concerned to look and to make the present from it”. His present, however real to him, was not always recognisably that of others’.

Ayrton’s intellectual habits were ingrained at birth. His father was Gerald Gould, a poet, fellow of Merton College, Oxford, and influential literary critic for the Observer, while his mother was Barbara Bodichon Ayrton, a suffrage activist, MP and later chair of the Labour Party. When Michael Ayrton became an artist he took his mother’s maiden name so as to appear higher up on the alphabetical list of artists in mixed exhibitions.

First though there was school – which he left at 14 – bouts of ill health and an artistic training, then there was a journey to Spain at the outbreak of the civil war in an attempt to join the republican forces. He was underage and his mother had him sent back and packed him off to relatives in Vienna instead, where he met Sigmund Freud. In 1939 he was in Paris, sharing a studio with John Minton, whom he had first met at the St John’s Wood School of Art. They had a mutual interest in the neo-romanticism of Pavel Tchelitchew and Eugène Berman. Back in England, with the outbreak of war, they joined the British part of the movement, which included Graham Sutherland, John Craxton and for periods both Paul Nash and Henry Moore, and produced work – especially landscapes – that was personal, poetic and visionary.

***

In 1940, at the age of 19, he and Minton were commissioned by John Gielgud to design sets and costumes for a production of Macbeth, which Ayrton worked on both after being called up for the RAF and on being invalided out of the service with a throat abscess. Within a few years he had become an art teacher, a regular writer on art for various magazines, had published his first book (on British drawing) and become the youngest panellist on the BBC radio programme The Brains Trust.

In the first year after the war, Ayrton visited Italy and was particularly struck by the work of the early-Renaissance sculptor Giovanni Pisano, and sculpture increasingly took the place of painting in his art. As he expanded his skills he was aided by technical advice from Henry Moore (he would later make a wonderful drawing of Moore playing table tennis) and inspired by his travels to Greece, which started in the late 1950s and which brought the Minotaur-Daedalus-labyrinth myth to the fore.

[See also: The dreamy nocturnes of Donato Creti]

His obsession with the story found its ultimate expression when in 1968 Armand Erpf, a plutocratic American banker and art collector, commissioned Ayrton to build him a maze at his estate at Arkville in upstate New York. The result was a structure comprising 1,680 feet of passages with walls 18 inches thick and eight feet high. At its centre were two coils in the shape of a double-headed Cretan axe with a seven-foot-high bronze statue of Daedalus occupying one and a mirroring sculpture of the Minotaur in the other. It was the largest brick and stone labyrinth built since antiquity.

***

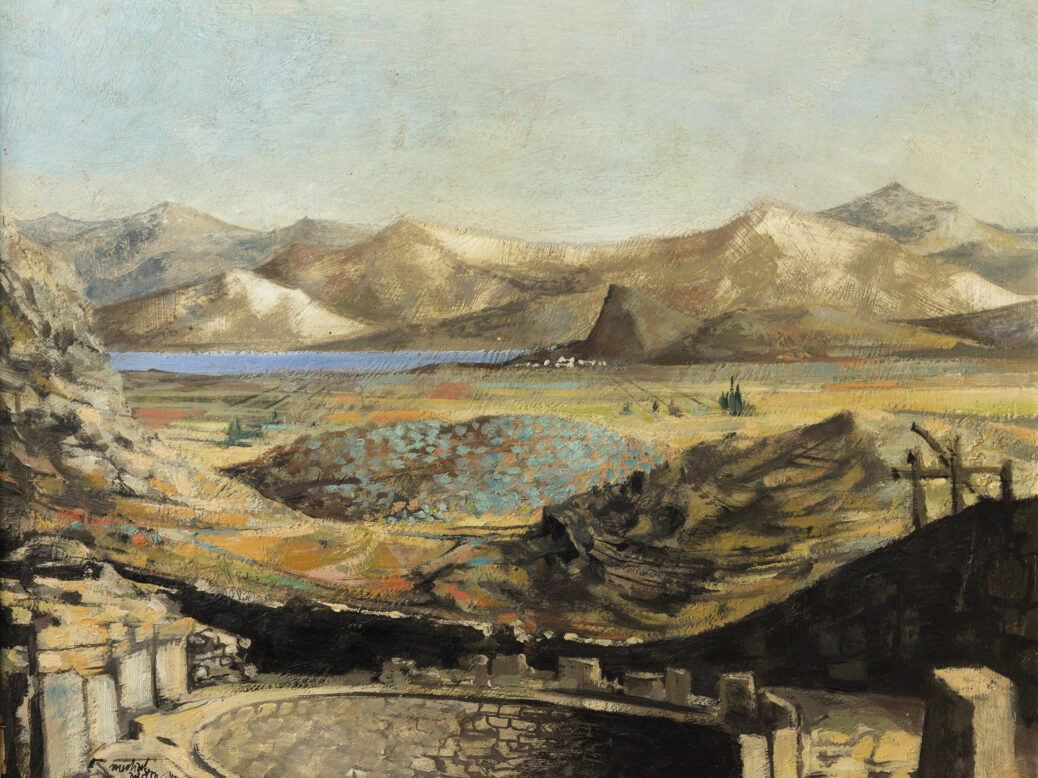

This painting, Mycenae I of 1957, shows the beginning of his thinking about pre-classical Greece and the origins of that New York State maze with its stone walls and curves. Homer described Agamemnon as “king of Mycenae, rich in gold” and the excavations that started in the Argolid plain in the mid-19th century gradually revealed the fabled city and powerfully linked myth with modernity. In the foreground of Ayrton’s painting is the structure known as Grave Circle A, the site that had yielded the famous golden “Mask of Agamemnon” and a great deal of other burial goods. This, for Ayrton, was hallowed ground where deep time was tangible.

For his picture, Ayrton stood in the middle of the ancient citadel looking south-west with the Lion Gate, mentioned by the second century AD geographer Pausanias in his Description of Greece, just to his right. The view is not exact – the mountain peaks, for example, are not as crisply triangular as Ayrton has them – but the mood is perfectly captured. No humans are present and the countryside has taken on the same bleached, biscuity tones as the stones of the citadel.

According to Ayrton, “to practise an art is primarily to discover one’s relationship with reality” and in this painting his reality is a complicated thing. The segue between ancient and modern is seamless: here, unchanged, is the view that Helen would have seen as she was abducted by Paris and that the vengeful Agamemnon took in at a sweep as he led his men off to the Trojan War. This is the homeland he and his troops dreamed of while encamped at distant Troy. This is the prospect that greeted the king on his return from war before he was killed by his wife Clytemnestra’s lover. All this Ayrton could almost touch. What he painted in this picture is both a real view and an imaginative one.

Ayrton wrote of “a stony, shining haunting of the spirit which came out of the ground for me in Greece” and the emotions stirred by the land and the myths stayed with him to the end: one of the last works he conceived, just before he died of a heart attack aged 54, was a statue called Minotaur Erect. Nor did he lose his fascination with the maze – everyone carries a personal maze “in his own brain”, he said, “we all have within our heads several personalities, intelligences”. Ayrton just had more than most.

[See also: An anarchist on the Riviera]

This article appears in the 10 Sep 2021 issue of the New Statesman, Labour's lost future