On a Tuesday morning in the main gallery of London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), seven people are gathering behind a large cellophane bubble for a photo. The photographer suggests they all lean against it, and demonstrates how he wants them to pose, arms outstretched, pushing against the bubble. “Don’t touch it!” a couple of members of the group call out, insisting that they will mime the pushing action instead. They are cautious for a reason: together, they are Honey-Suckle Company, the multi-disciplinary arts collective whose new exhibition opens at the ICA this week – and they don’t want anything breaking at the 11th hour.

In their assortment of beanie hats and patchwork jumpers, the ramshackle group look like a particularly eccentric bunch of east London hipsters. Honey-Suckle Company, founded in Berlin in 1994, is an artistic movement currently made up of Peter Kišur, Nina Rhode, Simone Gilges, Nico Ihlein, Lina Launhardt and the musicians Konrad Sprenger and Eleni Poulou. Both influenced by and experimenters with photography, music, fashion, film and sculpture, the collective straddles the line between being an underground, left-field cult and a commercial artistic project. The artists live and work collectively and were originally inspired by their shared belief in the alternative medicine homeopathy, but have exhibited in established art-world spaces such as New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Berlin Biennale.

Over four main gallery spaces at the ICA lies Omnibus, the first ever survey of the collective’s work. The exhibition is short but densely packed. In the first and largest gallery, the floor has been raised to house a vast, space-age sand pit; the theatrical set-up for NEUBAND 2000, a rock group of automaton mannequin-musicians playing in front of a metallic planet-like disc. The futuristic scene is strikingly lit by the bright autumn sun flowing in through the windows, and appears all the more strange thanks to the backdrop of black cabs driving down the Mall and tourists flocking towards St James’ Park across the road beyond. But Honey-Suckle Company’s work welcomes contradictions: stepping into the next room, done up to look like the black and white tiled interior of a public toilet, I almost trip over a Jil Sander shoebox that contains a bill for €460 and a dead rat.

Notably, every work is attributed just to “Honey-Suckle Company” rather than any individual member or members (occasionally collaborative musicians and artists not formally part of the Company are credited too). “One of our therapy methods from the beginning was to destroy ego,” Peter Kišur, an artist, healer, stylist and the Company’s founder tells me as we perch on stools in the ICA cafe. In the early days of Honey-Suckle he watched other collectives break up as some members found major gallery representation while others were left behind. “We never wanted that to happen to us,” Kišur says. “When we make a work, it is important that it is a Honey-Suckle product.” The talents of each of its members are shared out, too, with each Honey-Suckler working across mode and form. “We have people who are masters in pottery. But maybe somebody else would make pottery. The fashion designer won’t make clothes – the fashion designer will make a chair, maybe. And then everything comes together in the end.”

Honey-Suckle Company was spawned from a very singular period in time. “Twenty-five years ago, there was only one city in the world with Berlin’s political situation,” Kišur explains. “Squatting was not like how it is now. It was easy to squat anywhere, because there weren’t property owners. People from all over the world moved to Berlin because it was so cheap.” Born out of the post-reunification and pre-internet contexts of Berlin, in the Company’s early years the Honey-Sucklers were most concerned with collective care and communal living rather than corporate or commodifiable aesthetics. Most important was an honest display of selfhood, an idea Kišur describes, in a very literal approach to wearing your heart on your sleeve, as “gaffer-taping your own identity”. Between 1994 and 1997, the group produced collections of clothing held together with duct tape and worn by Honey-Sucklers not just in performance but in their day-to-day lives too. “This was our DNA from the beginning. Nothing was sewn. The jackets of the time were walking galleries. It was the analogue Instagram.”

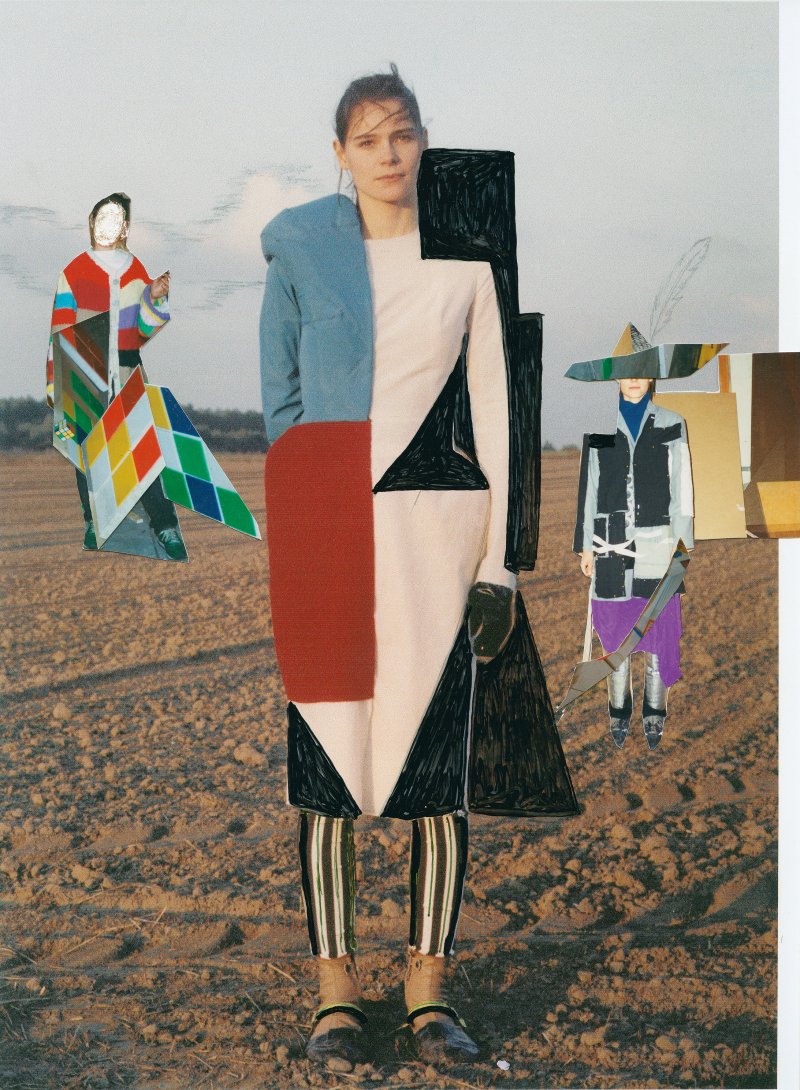

In the 2000s they looked towards the early 20th-century idea of Lebensreform (“life-reform”), a movement that promoted a back-to-nature lifestyle that encouraged organic foods and alternative medicine. This influence is evident in Eaude (2005), a photographic series of folkloric scenes of androgynous figures in rural landscapes. In many, faces are blurred – a sense of anonymity in collective living rings out through many forms in the Company’s work. Lebensreform was later co-opted by extreme right-wingers with national-socialist ideologies; as with many of the ideas that Honey-Suckle Company works with, a label of simply “good” or “bad” isn’t ever enough. Time changes meaning.

In homoeopathy, the honeysuckle flower is often thought to help you learn from past experiences and have trust in the future, in order to feel content in the present day. This ethos shaped Honey-Suckle Company’s formation. But 25 years later, Kišur sees things differently. “Now, I’ve found out that time does not exist,” he tells me seriously. “It’s simultaneous, and it’s layer over layer over layer.”

Omnibus, he explains, is a way of displaying this understanding of temporality. The first room, with NEUBAND 2000 and Bubble, “is the room where time doesn’t exist.” Bubble, for example, was first conceived of in 1995 but redeveloped this year – so it carries two years of origin; while NEUBAND 2000 has had many lives, as both an installation and a performative ensemble. The upper gallery, where 2006’s fabric-heavy Non Est Hic takes centre stage, and where a squawking siren intermittently rears its head from a hidden speaker, “is what it’s really like now,” Kišur says. “The whole situation on this planet is like a ship without a deck, with souls or voices behind the curtains but no control of the ghosts of the past.” The final and most arresting room, entered via a low doorway, contains Materia Prima (2007) – a sloping structure painted all white, making the space void-like. “The room of emptiness is, in a way, like the future for us. It’s the reset.”

Over the course of our brief conversation, Kišur moves between talking about Susan Sontag, punk music and the avant-garde Russian artist Kazimir Malevich, and also shows a keen but sceptical interest in the world of high fashion. Before his death, Karl Lagerfeld bought a copy of the Company’s book, spiritus, he tells me, and the clothes of Comme des Garçons and Yves Saint Laurent have been inspirations to the collective too. Honey-Suckle Company, though, is “more like an imaginary couture house”.

“Everything we did was about the zeitgeist,” Kišur tells me, and their original communal ethos may be just so. But, looking at his list of reference points – of influences which span periods in which Honey-Suckle Company did not yet exist – it seems these artists have always dug around in the work of revolutionary thinkers to seek out their own focal points, be they of the same era or not. Rich with cultural signposting, Honey-Suckle Company sets its own agenda.