I don’t recall ever meeting a monied Jew when I was growing up in Manchester. We certainly didn’t know any. A few comfortable ones, maybe – but the rest of us worked hard to make ends meet, some improving as the country itself became more prosperous, others just getting by. The two big events in my family’s financial history were my father’s having to pawn my mother’s engagement ring and his accidentally leaving £50 in cash in a public phone booth. He’d sold our old car to a friend and was calling my mother to give her the news that we were solvent for another couple of months. He didn’t notice he’d lost the cash until he got home. He never retrieved it but was able to redeem the ring when he became a taxi driver. So the idea that Jews were money-sympathetic as though by necromancy – money-adept, or just money-aware – struck us as laughable.

The first object to catch your eye when you begin to walk around the excellent exhibition at the Jewish Museum London, Jews, Money, Myth, is a dictionary from the 1930s open at the entry for Jew: “Jew, v, colloq. 1845. trans. To cheat or overreach.”

I still remember the disconcertment I caused one of my closest schoolfriends when I told him that “Jew” wasn’t a legitimate verb and that it didn’t mean to steal or cheat. I wanted him to know how much it upset me that a person who knew me should think it did. Have I ever cheated you, I asked him. Have I ever struck you as more interested in money in any of its aspects than you are? He apologised so profusely that I ended up having to apologise to him. He was innocent of malice. “You Jewed me” was common schoolyard usage right up to 1960 and, for all I know, beyond. Whatever pain was caused by it was rarely intended. The offence belonged to language.

Jews, Money, Myth takes the fight back to the beginning in order to show how the idea of the Jew as money-grubber grew from the earliest days of Christianity until it became so inwrought in words and images that even today the association is thoughtlessly assumed, by the educated as much as by the ignorant. The Jew has accrued many calumnies, but the imputation of greed and profiteering remains the most persistent and repugnant. Even when you know the history of the libel you are not proof against it. Let a Jewish businessman light up a cigar or allude to profit on television and I bury my face in my hands. I am told this is its own form of anti-Semitism. Would I deny a Jew what I’d deny no one else? In the circumstances, yes, I say. The circumstances being the thorough job the early libellers made of decoupling Jews from generosity and kindness, the very qualities that are the first to be inscribed in Jewish law and that still, for most Jews, determine what they live by.

[See also: The new class war]

The exhibition begins with a stern rebuke. “Money has symbolic as well as material value in Jewish life. According to Jewish customs, it is not a sin to be wealthy, but money must be used to serve God and to support the wider community.” We are not, then, going to apologise for being a religion that embraces the things of the world. There are religions that shrink from life: Judaism is not one of them. But wherever earned, whether accumulated by the rich or scraped together by the poor, money bore a responsibility.

Throughout the Torah there are exhortations to give generously and be charitable. “Therefore,” commands the God of Deuteronomy, “thou shalt open thine hand wide unto thy brother, to thy poor and to thy needy.” The possessive pronouns – thy poor, thy needy – enforce the suggestion that it’s an obligation of the heart to be generous. Tzedakah, a Hebrew word that has come loosely to denote charity, in actuality means righteousness. Thus, to fail to give charitably – a third of one’s income, some say – is not simply to neglect one’s social obligations, it is to fail as a spiritual being. There is, then, a particular vileness in attributing tight-fistedness and greed to a people for whom generosity and open-handedness lie at the heart of religious life.

Tracing the history of a slur is no easy business. It’s tempting to see the figure of Judas as the father of it, but human betrayal is as much the overarching sin in the Judas story as the 30 pieces of silver. If the verb Jew came to mean to swindle, then Judas became, and indeed remains, a byword for all else that’s reprehensible in the supposed Jewish character: inconstancy, duplicity, treachery, hardness of heart. This isn’t to say the 30 pieces of silver are merely incidental, but they count for less in the early versions of the narrative than they will later. Christianity has first to make a clear line in the sand between it and the religion of which it is an offshoot, and the Judas kiss of betrayal does that better than finance. Altogether, early attitudes to Jews made nothing of their commercial deviousness. The Greek Sophist Apion, a resolute hater of Jews in the immediate years before Christ, found them obstinate but submissive, superstitious and incompetent. The Jew with the money bag on his belt would come later.

Judas was an invention from the start. Yes, all 12 apostles were Jews, but that fact would slowly disappear, as the only false one, who just happened to be named after the Jewish people, took centre stage.

He is known to us today largely through the paintings of the last supper that were to be the mainstay of medieval and Renaissance European art. There he is, often at the far end of the table, nursing the bag of silver, red-haired and yellow-cloaked – symbols of foreignness and duplicity both. Sometimes he is portrayed half-sympathetically, as in Rubens’s masterful study of an intelligent man looking deep within himself, and deep into the future too, but more often as the last person you’d want at your dinner table. It is not unknown for Judas to be painted with an erection, in reference to the lechery that was thought to be a side-product of Jewish acquisitiveness. Turn a profit and you get a hard-on.

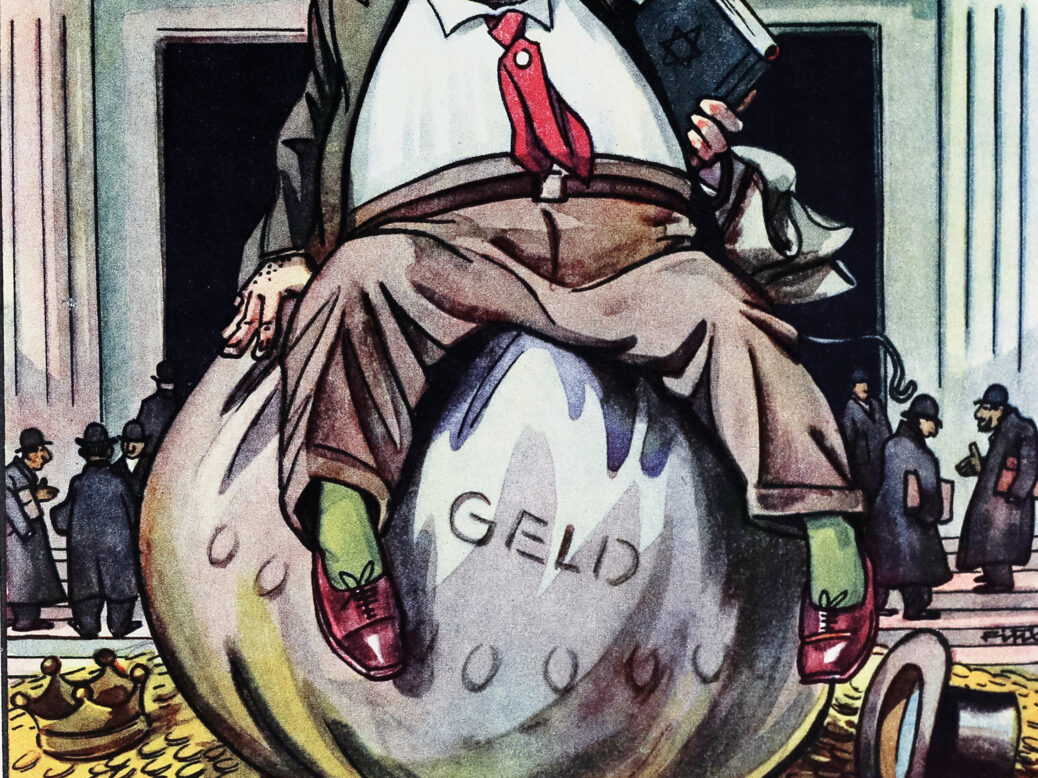

By the middle ages, the work of the church fathers has been accomplished and lewd acquisitiveness has come to be the mark by which Jews are known. The historian of Jewish history and medieval iconography Sara Lipton notes the emergence in the 13th century of allegorical illustrations in which “Jews were associated with despised creatures: ravens or crows, which were thought to hoard shiny objects; toads, whose swollen form mimicked the usurer, bloated with greed… It was around the year 1250 that the swarthy, hook-nosed, scraggly-bearded Jewish caricature was born… as an artistically naturalistic means of signalling the Jews’ alleged carnality.”

Judas kiss: detail from a 17th-century depiction. The Victoria & Albert Museum

She goes on to remind us that the point of much of this imagery was more to dissuade Christians from sin than to promote hatred of Jews, but this is a hard distinction to maintain. As we have discovered with the internet, once you let the imagery loose, there’s no policing its progress. By the time we get to the world that Shakespeare’s Venetians move in, the Jew as bad-faced usurer is both an ordinary fact of urban life and a figure of lurid imagining, which Shylock, in his boundless sarcasm, is not averse to encouraging. As you see me, so I will be. It’s a massively entertaining stratagem for audiences of the play – at least for those who appreciate Shylock’s speed of wit – but self-defeating in the end.

There have been real Jewish money-lenders and they necessarily figure in the exhibition. The case has been made again and again that if Jews became proficient in banking and associated sciences, that was because so few other professions were open to them. It’s equally well-known that by lending as they did, they salved the consciences of Christians who pretended “interest” was beneath them. Shylock is as good a critic of this hypocrisy as anybody: “The villainy you teach me, I will execute.” I will not myself accept it’s villainy to own a bank – hard though we find it to love both a banker and his bonus – but the suggestion that such villainy, as it is, originates elsewhere than in the poisoned hearts of Jews finds no takers in the caricaturists who have been monstering Jewish financiers and philanthropists for the past 300 years. For the worst example of which, at least in this exhibition, see Jean-Pierre Dantan’s 19th-century sculpture of Nathan Mayer Rothschild as something beyond recognition even in the animal world.

The imagery Sara Lipton describes – if you like, the very map of the inside of Shylock’s tormentors’ minds – is powerfully present on the walls of the exhibition. Were I to believe in trigger warnings I’d recommend them to prepare visitors to this show, so viscerally repugnant are the cartoons and posters the curators have unearthed. Toads bloated with greed are not the half of it. While we will all have seen some of this material in situ on our travels round the anti-Semitic world – for which read, it distresses me to say, just about everywhere – it is the universal prevalence of them, gathered in one place, making a few little rooms an everywhere of undisguised abhorrence, that shocks.

[See also: Stop dithering, British Museum – give the Elgin Marbles back]

I could say frightens, but the shock comes first. What goes on in the heads of those who see this stinking hell of malformation and malevolence the moment they imagine a Jew? You could spend time trying to decide whose imagination is the most diseased: that of the medievalist or the modern, the fascist or the communist, the despot or the social reformer? As often as not the imagery is interchangeable. There can be only one explanation for that: the Jew as swollen-faced usurer, manipulator of media and puppeteer of nations, the Jew as rat or toad or malformed beast that is yet to be classified, answers to some dread of miscreation that the human mind cannot stop manufacturing. That the crime of usury and the spectacle of wealth do not themselves in any way explain this dread is proved by the ugliness with which immigrant and poor Jews have also been described. Could it be – remembering Freud’s equating of money and faeces in the unconscious – that, deep down, the materiality of life itself horrifies us, and that the Jew serves the purpose of giving that horror a name?

The Jew goes on being invoked anyway, whether to malign or mischievous end, wherever societal malfunctioning or private misfortune needs to be accounted for. It takes the breath away that kitsch figurines of “lucky Jews”, or Zydki, are this very minute being sold on Polish markets. Made of ceramic or plasticine, with small coins appended, these figures serve a talismanic purpose. Keep one by you and the Jew’s good fortune might be passed on to you. Turn upside down and it will fall into your lap. It is worth taking time to ponder that: the Jews’ good fortune, in Poland!

Not the most chilling exhibit here, but certainly the most topical, is a small, discreetly placed reproduction of the notorious Brick Lane mural showing unmistakable caricatures of rich Jews playing Monopoly on a board supported by the naked backs of the world’s oppressed. In 2012 Jeremy Corbyn questioned a decision to remove the mural; he later claimed not to have noticed that it was anti-Semitic. Might he have known better had he seen this exhibition? Truth to tell, such images of bent-nosed, predatory Jews and the nexus between them and money have been around for centuries and are well-known to any moderately informed person. For Corbyn not to have seen what was screaming at him from the wall – obvious at a moment’s glance – bespeaks either a terrifying ignorance or an even more terrifying concurrence.

Jews, Money, Myth is a fine, educative experience. But there is a knot of pessimism that education can never untie: much as knowledge shines light on man’s erroneousness, it teaches how quickly the dark descends again. How to prise a murderous libel from the language and visual imagery of its expression is a challenge at any time. But we have the ideologies of extremists, the hate-propagating internet and a strange passion for forgetting to contend with. We have our work cut out.

Howard Jacobson is the author of “Live a Little” published by Jonathan Cape