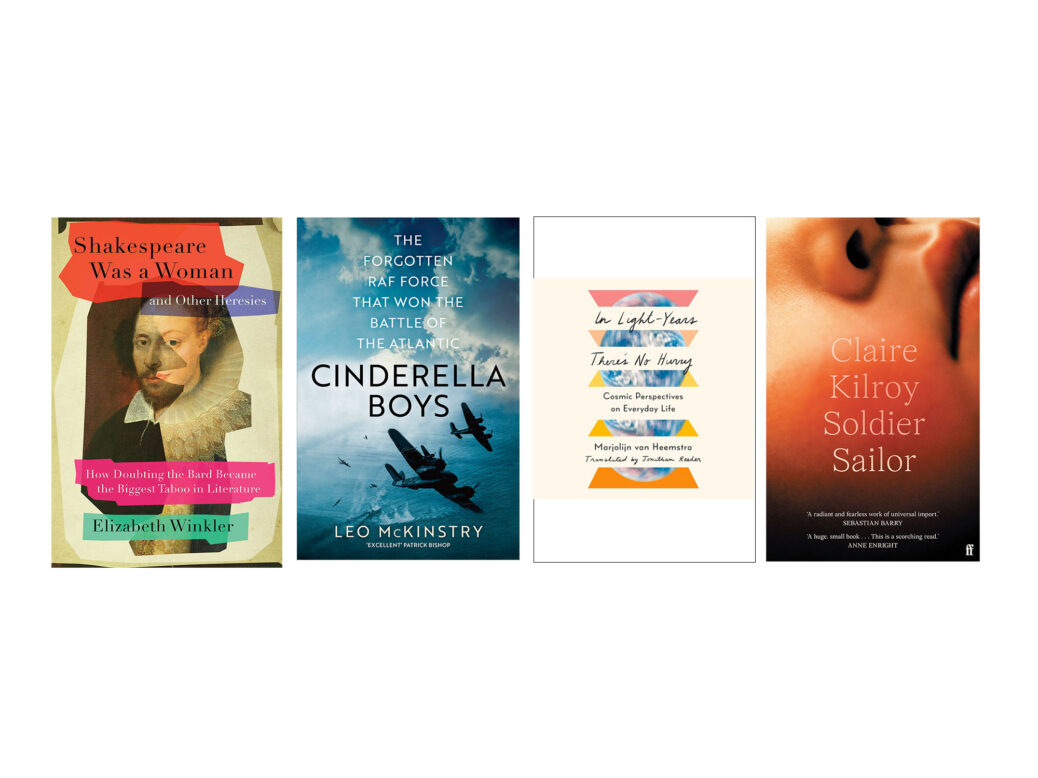

Shakespeare Was a Woman and Other Heresies: How Doubting the Bard Became the Biggest Taboo in Literature by Elizabeth Winkler

Simon & Schuster, 416pp, £20

Shakespeare was not simply a man – he was a god. Or, at least, he is a god to many readers today, and many more through history, as Elizabeth Winkler tells us in her book exploring the question of whether William Shakespeare, born in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1564, wrote the works we attribute to him today. The scholars who answer in the affirmative (“Stratfordians”) are his “representatives, interpreting and mediating for the masses the meaning of Shakespeare, and so, like the priests of the sun god Apollo, they glow with the radiance cast by his rays”. To question Shakespeare’s authorship – to argue that his plays are the work of the aristocrat Francis Bacon or rival playwright Christopher Marlowe – is a “heresy”: “No one takes kindly to the denial of his god.”

In 2019 Winkler wrote an essay for the Atlantic titled “Was Shakespeare a Woman?”, making the case for Emilia Bassano – the first woman in England to publish a volume of poetry – as author of the plays, and was shocked by the outrage it generated. She enjoys dramatising the “taboo” of her topic – but that makes her book all the more fun to read. Here, dusty, scholarly disputes seem scandalous, high-stakes and thrilling.

By Anna Leszkiewicz

[See also: Shakespeare’s race problem]

Cinderella Boys: The Forgotten RAF Force That Won the Battle of the Atlantic

by Leo McKinstry

John Murray, 336pp, £25

The Cinderella Boys – the airmen of Coastal Command during the Second World War – were, like the fairy-tale figure from which they took their name, overlooked. As the wing of the RAF in charge of maritime operations they were a world away in glamour from the fighter pilots and bomber crews. Nevertheless, during the Battle of the Atlantic, when German U-boats menaced the North American supplies on which Britain depended, their role was crucial and the fight to counter the submarines relentless. Operational tours, scouring the sea for German warships and merchant vessels, could last for 800 hours, and bombing and depth charging took place at perilously low levels: 8,874 members of Coastal Command lost their lives.

Leo McKinstry, an adroit and thoughtful historian, here relates the experiences of the Cinderella Boys compellingly. He recounts the Atlantic missions, the force’s work in the Mediterranean, meteorological operations, and search and rescue sorties. As McKinstry makes clear, Coastal Command was vital for the success of the Normandy landings, as well as for sinking or damaging 500 German submarines.

By Michael Prodger

In Light-Years There’s No Hurry by Marjolijn van Heemstra, translated by Jonathan Reeder

WW Norton, 160pp, £21.99

There are some books that come to you in moments of need. In the midst of an anxiety spiral at the dire state of the world – the politics, the climate, the existential threats facing humanity – In Light-Years There’s No Hurry felt like a balm. It does not shy away from hopelessness and fear. Instead, it looks calamity directly in the eyes and asks what we can do to see things differently.

For the Dutch poet Marjolijn van Heemstra, the answer is to change our point of view. Returning astronauts describe a phenomenon known as “the overview effect”: a feeling of awe and connectedness to everything around them after viewing the Earth from space. “We are all astronauts, but we keep forgetting it,” Van Heemstra writes as she begins her quest to experience this cosmic shift in perspective without leaving the atmosphere. In this poetic exploration of zooming out, she investigates the realities of modern-day space travel and walks through forests at night to seek out true darkness. Can looking at the stars help reset our relationship with our home planet, and with each other? I don’t know, but I’m going to try.

By Rachel Cunliffe

Soldier Sailor by Claire Kilroy

Faber & Faber, 256pp, £16.99

“Love is the most eccentric property I know of,” declares Soldier, the protagonist of Claire Kilroy’s new novel. “Endangering it only serves to reinforce it.” Soldier is a mother, drowning in the sleep-deprived, all-consuming haze of early-years parenting. Her baby, Sailor, is the centre of her world, but the responsibility of caring for him alone seems to be constantly on the verge of overwhelming her.

In a visceral and at times frenzied first-person narrative, Soldier reveals to her son her truth about his infanthood; the rage she feels towards her husband for his emotional absence, the frightening near misses of Sailor coming to harm, her loneliness, and indignation when she is called a “stupid woman” for taking up space with her pram on a pavement. These feelings sit alongside Soldier’s tender declarations of love for Sailor, and her deep fear of ever being without him. Kilroy’s fifth novel – and her first for ten years – is an arresting portrayal of the emotional volatility of motherhood. In Soldier, the author speaks to the joys of having a child, but also fearlessly confronts the inevitable strain it can place on a woman’s sense of self.

By Christiana Bishop

Purchasing a book may earn the NS a commission from Bookshop.org, who support independent bookshops

[See also: Jonathan Bate interview: “To me, Shakespeare is the great enabler”]

This article appears in the 28 Jun 2023 issue of the New Statesman, The war comes to Russia