On the morning of 6 April 1815, after a night of what sounded like “distant cannon”, the British overlords of Java sent a detachment of troops out from Yogyakarta “in the expectation that a neighbouring post was attacked.” They found nothing. The rumbling was, in fact, the initial stirring of Mount Tambora, on Sumbawa Island, 850 km to the east.

Four days later, Tambora exploded in the largest volcanic eruption in recorded history, blasting as much as 150 cubic kilometres of rock, ash and gas into the atmosphere. The results were catastrophic: 10,000 people died almost instantly, as pyroclastic winds tore nearby villages apart, followed by 50 cubic kilometres of magma. Perhaps as many as 100,000 more in the region died over the following days, battered by rock, ash and tsunami. The eruption also deposited enormous volumes of sulphur dioxide into the stratosphere, where it was transformed into sulphate aerosols. As the aerosols drifted east, a shockingly cold spring and summer struck parts of North America and western Europe. June brought half a metre of snow to Québec City, and double the average rain to Britain, France and much of Germany. The cold destroyed harvests, and bread prices doubled on both sides of the Atlantic. The eruption also left a permanent cultural mark in Britain: 1816 remembered as “the year without a summer” – provided the background for both Mary Shelley’s icy Frankenstein and Byron’s apocalyptic poem “Darkness” (“Morn came and went – and came, and brought no day”).

Tambora makes a brief appearance in Peter Frankopan’s The Earth Transformed: An Untold History and it provides something of a window into this sprawling history of the planet, its people, and the relations between the two. Volcanoes do loom especially large in Frankopan’s account – he argues they pose “by far the biggest risk to global climate” – but more importantly, Tambora captures the ways humans have responded to, and created, large-scale environmental change, from mass migrations to emptying the oceans to schemes like damming the Bering Strait to warm the Arctic.

Frankopan says the book shows “how our world has always been one of transformation, transition and change because, outside the Garden of Eden, time does not stand still”; and he is being modest: the Garden of Eden receives a fair bit of coverage. These histories are the substance of the elaborate but sometimes unconvincing lattice of causal networks that make up his account of the planet and our relationship to it.

Ambition is the book’s signal merit: Frankopan sets himself the task of “reintegrating human and natural history”. The labour of assembling it must have been as monumental as the book’s aim: retelling the story of the coevolution of humanity and its endlessly diverse home. For Frankopan, this requires an emphasis on three themes: climate and weather and their determinants, human transformations of the natural world, and the breadth of phenomena that should count as “history”.

The book begins just after the Big Bang and ends yesterday. There is little of the planet and its people that is not accorded at least some attention, and much of it, especially those parts for which there exists sound archeological or recorded evidence, gets quite a bit: Neanderthals and other hominids, China ancient and modern, the Mongols, Mesopotamia, Ottomans, Vikings, Egypt, the Arabian peninsula before and after Mohammed, Europe and the British Isles, the Incas, Aztecs, Mayans and modern Latin America, Japan, Polynesia, North America before and after colonisation, sub-Saharan Africa, Russia, India, Korea and Cambodia. You name a place and time, it’s probably in there.

Similarly: plate tectonics, floods, meteor strikes, droughts, volcanic eruptions, sunspots and solar winds, earthquakes, monsoons, locusts, malarial mosquitos, plague, tsunamis, everyday weather good and bad, not to mention the slave trade and plantation agriculture, colonialism, invasive species, technology, extinctions, migration and urbanisation, trade networks near and far. Reading it can be overwhelming, like being caught in an historical particle accelerator, bombarded with everything from the Xia dynasty’s flood management efforts in 2000 BCE to the history of the colonial guano trade to the position of the boreal Hadley cell (atmospheric circulation between the equator and about 30°N).

[See also: Hail the assassins]

The task of putting all this into a narrative is the real challenge that The Earth Transformed confronts constantly over its 736 pages. Frankopan is aware of this. He notes throughout the risks of over-simplifying, of overlooking difference, of downplaying historical and geographical context. He also flags the temptations of environmental determinism, especially in the shadow of catastrophic global heating, which was clearly what motivated him to write: “We should be looking at the wider question of why societies struggled, rather than being tempted by the convenience of a simple and even a seemingly logical answer that starts and finishes with climate.”

But when someone gathers all this material and shakes it through their historiographical sifters of method, theory and narrative, the result must have some kind of argument. The question of how to think about the problem of historical cause – what are the drivers of all this transformation?—lurks in all the book’s twists and turns. Perhaps it’s understandable in work of this scope and scale, but it’s unclear what Frankopan wants to tell the reader that they might take with them into the future, how he wants us to manage and sort the material he has amassed. Yet if we want to understand how to reintegrate human and natural history – especially at the scale of billions of years, during almost all of which there was not a human to be found – we have to theorise the relationship between humans and their environments.

This is something Frankopan seems reluctant to do, perhaps because he doesn’t want to seem so arrogant as to develop a “theory” of planet Earth. If so, I have some sympathy. Yet a theory does appear to have helped him organise his account even if he doesn’t articulate it, and since it is left unsaid we have to use our own gins to spin the thread.

What are the historical forces at work in The Earth Transformed? When the story is about everything through all of time, arguments about what causes what can get so frayed it becomes difficult to know what purpose they serve. There is something at once both vitally important and pointless, for example, in arguing that Earth system dynamics during the Cretaceous period or Carboniferous era shaped modern geopolitics via the “environmental lottery” that determined the planetary distribution of fossil fuels, or that the rise of British sea power and the outcome of the Second World War were made possible by the collapse of an oceanic shelf off Norway in around 6150 BCE. It is undeniable, as Frankopan says, that “had there been no oil or gas in the Middle East, things would have been very different”. But if that is something worth thinking about, it is unclear why. Not to be glib, but we could just as well say that the Big Bang “fuelled human history”, or that “had there been no oxygen, things would have been very different.”

It is true that the global distribution of the materials that became natural resources is the result of unplanned geophysical processes unfolding over billions of years. It is also true that climatic or tectonic events have always had a huge impact on how human and non-human communities have made their lives (or not) on this tumultuous sphere. Bringing the specifics to light gives us a fuller understanding of the forces with which those who preceded us had to contend – and makes us think about the power of those same forces now and in the future.

But this approach to “reintegrating human and natural history” ends up interpreting the arc of human-environment relations as the result of the confluence of humanity’s “natural” adaptive tendencies and what Frankopan calls the “luck of the geological draw”: “Contemporary anthropogenic climate change, global warming and pollution are all fuelled, in other words, by shifts that took place over the course of hundreds of millions of years.” But there is nothing in those “shifts” that had to lead to the current situation, nothing meaningfully causal, even if we reduce cause to mere constraint. In this account, cosmological chance billions of years ago, as well as more recent “serendipities” like Tambora, function as random natural determinants of the evolution of human communities, whose responses are fundamentally the same, no matter who they are. Despite our vast geographical and cultural variation, everyone everywhere mostly acts like an agent in a neoclassical economic model, an optimiser responding to changing incentive structures. Indeed, this is how large portions of The Earth Transformed reads: “Since its beginnings – whenever or wherever those may be – our species has expanded, colonised, reproduced, created and dominated, but it has also destroyed, devastated and exterminated. It has done so better than almost any other organism that has lived in the last 4.5 billion years.”

But the emergence, for example, of imperialism in its poisonous varieties, British and otherwise, is the outcome of neither geological luck nor of peoples’ regrettable but “unsurprising” – a term Frankopan uses frequently – response to the constraints of their time and place. Frankopan is no apologist for colonialism, the slave trade, or any other aspect of the imperial project. But ascribing to “us” humans an “unsurprising” species-wide tendency to act like power- and wealth-seeking rational actors leads him to naturalise the past – to depoliticise it. Recounting one of Britain’s “more shameful episodes of destruction” following the 1897 murder of a colonial commissioner in Benin, for instance, he claims that at the time, teaching the people of Benin a lesson “seemed perfectly natural”. The suggestion, I suppose, is that the Oba of Benin would have done the same thing if positions had been reversed, or at least that any offended Englishman would have acted similarly. I am not so sure.

While Frankopan is attentive to imperial extraction and the ways it has ravaged the world outside Europe (and enriched many on the inside), there is hardly any mention that, especially by 1897, colonialism was a part of another British-dominated global system: capitalism. Throughout the colonised world, the state-corporate mode of resource depletion and genocide – no other word will do – was (and in many places still is) driven not by “unsurprising” human acquisitiveness and competition, but by the expansion of markets and consolidating processes of accumulation that even conservative historians are now comfortable naming as capitalism. But the term “capitalism” almost never appears in The Earth Transformed, and when it does it is only as a brief notation, never an historical phenomenon. Frankopan does note that something new started happening around 1500 – the beginning of a “cycle in global history” driven by “the pursuit of profit” – but that is as close as he gets, and even then he does not regard “the pursuit of profit” as distinctively capitalist, since he also mentions its pursuit in 2500 BCE.

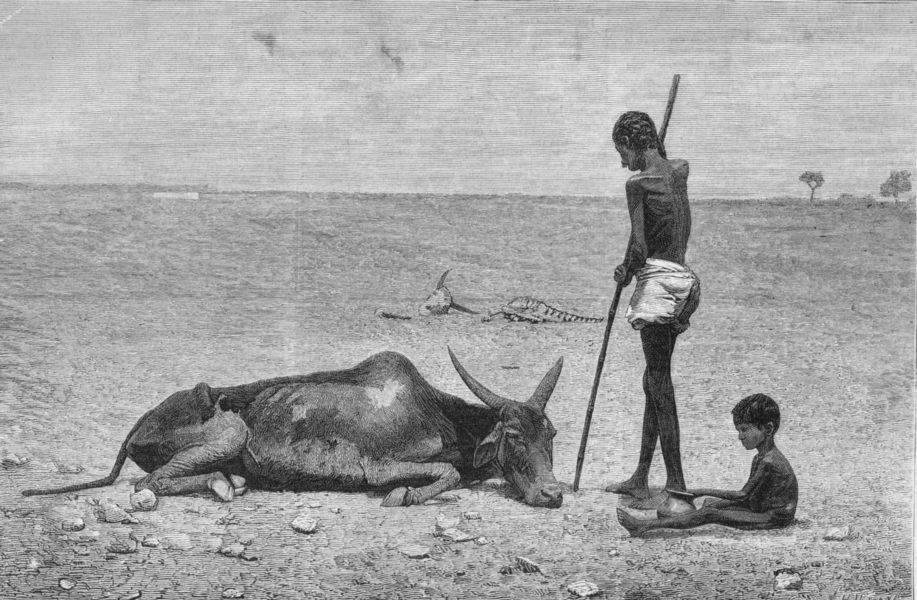

This silence raises important problems, and questions about Frankopan’s underlying assumptions regarding historical change. One of the more striking instances is an account of the famines that overwhelmed India in the second half of the 19th century. Frankopan does not refer to it, but the late Mike Davis’ Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World (2000) presents a meticulously researched history of climate science and colonialism at precisely this moment in history. He shows how British imperial administrations took advantage of climate variability to starve perhaps 80 million people to death across the global south, congratulating themselves on climate’s usefulness in subduing the “natives”. In contrast, Frankopan, describing a pre-independence famine in 1940s India that killed perhaps three million people, remarks that “unlike most famines in India in the later 19th and 20th centuries, the catastrophe in Bengal was mainly about human error, rather than monsoon failure and problems of soil moisture.”

To leave capitalism virtually unmentioned in a planetary history of the last two centuries would suggest it is not worthy of mention. Why does Frankopan make this choice? My sense is that the ecological-evolutionary perspective that organises the book is really his theory of history: “Nature does not care who wins or who loses… the issue is always about adaptation and survival.” Adaptation and competition are the primary motors of history, as are Malthusian cycles of abundance and then scarcity when we have made the mistake of “living beyond our means”. This homogenisation of human development leads Frankopan to take the politics out of history, or more accurately, to reduce political economy to another form of competitive adaptation, and the extraordinary variety of “civilisation” becomes the surface effect of universal forces.

The growth machine rumbling at the heart of global capitalism has realised a level of extractive destruction, pollution, mass extinction and eco-systemic collapse that is unparalleled in human history. The difference between it and anything before is not one of degree, but of kind. The so-called Great Acceleration, the process through which virtually every negative indicator of environmental health on the planet has become exponentially worse since 1945, is not the result of merely another human adaptation. The order of today is not just the result of a more resource-intensive version of adaptation – as if it is just human nature working itself out as always, but this time with more destructive tools – but of power in the hands of destructive historical forces that could have been otherwise. Just as not every civilisation has felt it necessary to destroy their neighbours, there are many civilisations who live more generously with the earth. Humans’ evolutionary competition for “adaptation and survival” does not make ruination “unsurprising”.

Confronting our future, in the wake of a century Frankopan describes as “a sequence of catastrophes unparalleled both in human history and in that of the natural world”, this ecological model leads him to a combination of alarmism and liberal progressivism, dark pessimism and techno-optimism. He says the “world of today and tomorrow looks terrifying”, and warns of the “horrors that lie ahead”. But he also notes that “ours is a story of resourcefulness, resilience and adaptation”, and “while contending with potentially catastrophic global warming in the course of the 21st century should not be downplayed, current projected rises of 1.5-2°C are modest in the grand scheme of climatic change, not only in the history of the earth but in that of humans too.” He reminds us that his book shows that “there have been a great many times in the past when societies, peoples, and cultures have proven unable to adapt”, but “the climate pendulum can swing both ways”, and there are “good reasons to be upbeat”. This mixture, it seems, is due less to uncertainty than to Frankopan’s belief that much of what is to come is beyond our control: the political-economic resources we might collectively develop to address climate change are no match for human nature.

Ultimately, he expects “nature” itself will likely solve the problem on its own, through “catastrophic depopulation”. That may be end up an accurate forecast, but if so, it won’t be because of the “nature” of the human species, but because of the dominance of one way of living and thinking over the many others that could have, and might yet, help us live more humbly with the Earth.

[See also: Why wealth trumps whiteness]

The Earth Transformed: An Untold History

Peter Frankopan

Bloomsbury, 736pp, £30