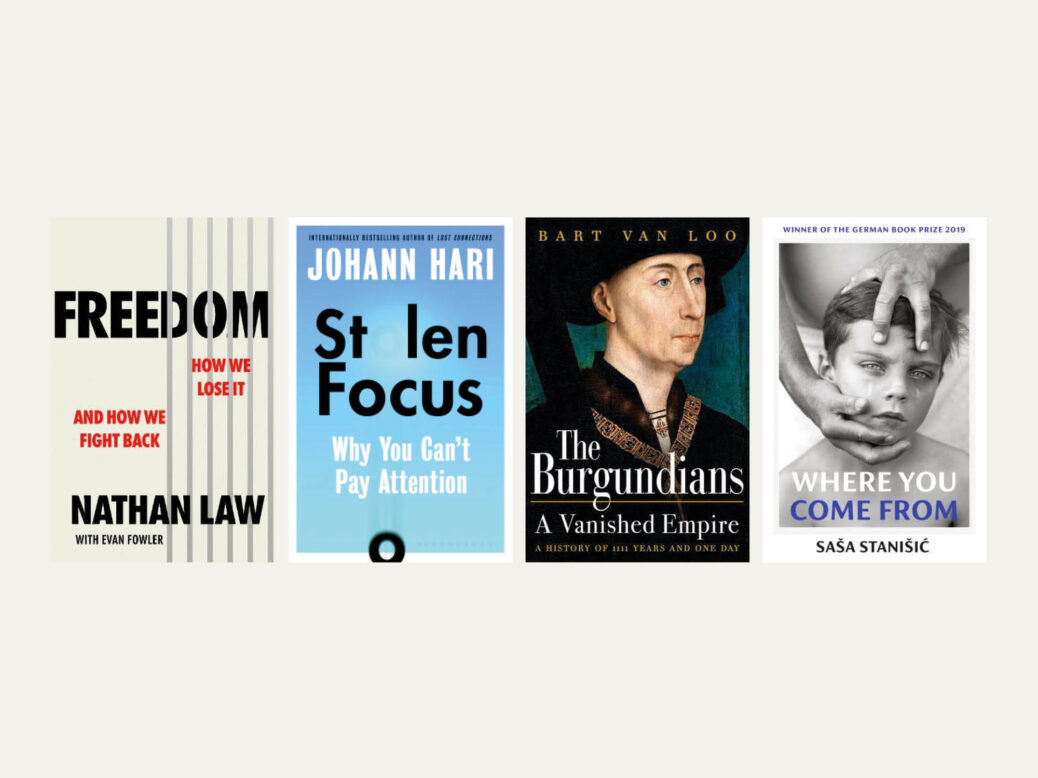

Freedom: How We Lose It and How We Fight Back by Nathan Law with Evan Fowler

Transworld, 240pp, £12.99

A nation’s slide into authoritarianism is a bit like falling asleep – it happens slowly at first, then all at once. That’s the message from the exiled Hong Kong activist Nathan Law. Throughout this book – one-part memoir, two-parts polemic — he charts Hong Kongers’ battle for democracy in recent years as the city has transformed from a vibrant financial hub to an island under Beijing’s control.

The book is at its best when dealing with specifics: when Law delves into his own personal ordeals, such as his mother’s anguish at his prison sentencing for organising protests as a student. But the lesson is that signs of totalitarianism were present in Hong Kong long before authorities instilled the draconian national security law in 2020. Law argues that those signs exist around the world, and therefore freedom shouldn’t be taken for granted in any country. With democratic ideals such as press freedom and the rule of law being increasingly eroded in nations including Hungary, Brazil and Turkey – and with election results still being called into question in the US – Law offers a warning and a wake-up call.

By Megan Gibson

[See also: Reviewed in short: New books by Ken Worpole, Craig Whitlock, Mary Roach and Ilya Kaminsky]

Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention by Johann Hari

Bloomsbury, 352pp, £20

The average American worker, one study shows, is distracted once every three minutes. In Johann Hari’s fourth book Stolen Focus, he notes that the phrase “multitasking” was originally used exclusively by computer scientists, until we created a damaging myth: that the human brain has the neurological capacity to work on more than one problem at a time.

Hari’s attempts to rehabilitate himself after his disgracing in 2011 (for plagiarising quotes and editing the Wikipedia pages of others) have been helped by a series of celebrity endorsements, though he still has plenty of critics. Here he argues that we are not simply addicted to our screens but are experiencing an “urgent attention crisis”. Drawing on interviews with experts and his own personal experiences, he identifies 12 “deep forces” at work, including the rise of manipulative technology, “the collapse in sustained reading” and the “confinement of our children”. Hari concludes that simply turning off our iPhones cannot solve this crisis. Instead, we need systemic solutions and a resolve to hold Big Tech accountable for the damage it inflicts on our everyday lives.

By Eleanor Peake

The Burgundians: A Vanished Empire by Bart Van Loo, translated by Nancy Forest-Flier

Head of Zeus, 624pp, £30

At its height in the mid-15th century, the state of Burgundy was a messy collection of duchies, counties and bishoprics that occupied a swathe of Europe, from the modern Netherlands and Belgium down through Luxembourg to extensive lands on each side of the Saône, centred on Dijon. Although, territorially, it couldn’t match its neighbours France and the Holy Roman empire it nevertheless wielded extraordinary power and influence before its dissolution in 1477.

Bart Van Loo’s lively, anecdotal unpicking of this fascinating but nebulous entity has already sold some 250,000 copies on the Continent and it is easy to see why. It mixes politics and war with art and a shifting cast of characters saturated with colour – from Philip the Good with his three marriages, 25 mistresses and 26 children to Charles VI, the French king who believed he was made of glass. It is a story too of patronage and mercantile nous which took the state – it was never a proper empire – to such heights that its disappearance and its lack of hold on the modern imagination seem unfeasible. If we have reached peak Tudor, the Burgundians are even more rewarding.

By Michael Prodger

[See also: Reviewed in short: New books by Margaret Reynolds, Michio Kaku, AK Blakemore and Jay Griffiths]

Where You Come From by Saša Stanišic, translated by Damion Searls

Jonathan Cape, 368pp, £16.99

Where You Come From, a critical and commercial success in the original German, is Saša Stanišić’s autobiographical novel of a family’s displacement following the Bosnian War in 1992. The protagonist, named Saša Stanišić, ends up in Heidelberg in Germany. Central to the author’s concerns are the details of assimilation: how can he master the German language, and what barriers might not doing so produce?

The book is most powerful in its gentle undoing of what learning a new dialect might seem (a simple memory game) and what it really becomes (a set of codes and customs). For the protagonist, language is “easy enough to pick up, but very hard to carry anything in”. Stanišić’s prose is calm, persuasively so. The story’s close, however, takes a different approach. Stanišić swaps the traditional form for a multiple choice, “Choose Your Own Adventure”-style finale. As the reader flits from page to page, exploring the possibilities of multiple endings, Stanišić recreates the literal back and forth of a displacement narrative, but one where the opportunity for self determination – typically stripped from people of refugee status – is imperative.

By Elliot Hoste

[See also: Reviewed in short: New books by Jan Morris, Siri Hustvedt, Mark Bould and Salley Vickers]

This article appears in the 12 Jan 2022 issue of the New Statesman, The age of economic rage