Who would have thought that the life of Monica Jones, an unpublished and under-promoted lecturer in the English department at University College, Leicester, would prove to be such a page-turner? We all knew that she was Philip Larkin’s long-term lover, and we thought we knew that she was reactionary, racist, homophobic, awkward, hysterical and dowdy. How wrong we were, how wrong. John Sutherland has set up a counter-narrative that keeps us guessing, as he himself has been kept guessing by this strange woman whom in some ways he knew so well, and in other ways, as he speculates, not at all. This memoir is his tribute to Miss Jones, and he shows her to us in her powerful prime. It is a story as full of surprises as many a novel, and a story that only he could tell.

The Jones-Larkin narrative has many subplots, including that of the academic politics that transformed the provincial, extramural college of Leicester (“porridge-thick with inferiority complex”) into a successful university, with a pioneering new department of sociology and a flourishing department of English graced by stars such as the professional northerner Richard Hoggart and the “highly metropolitan” GS Fraser. This doesn’t sound a very promising topic, but Sutherland, well placed to understand events in what is now his professional world, deals with it very well and with a scrupulously even hand.

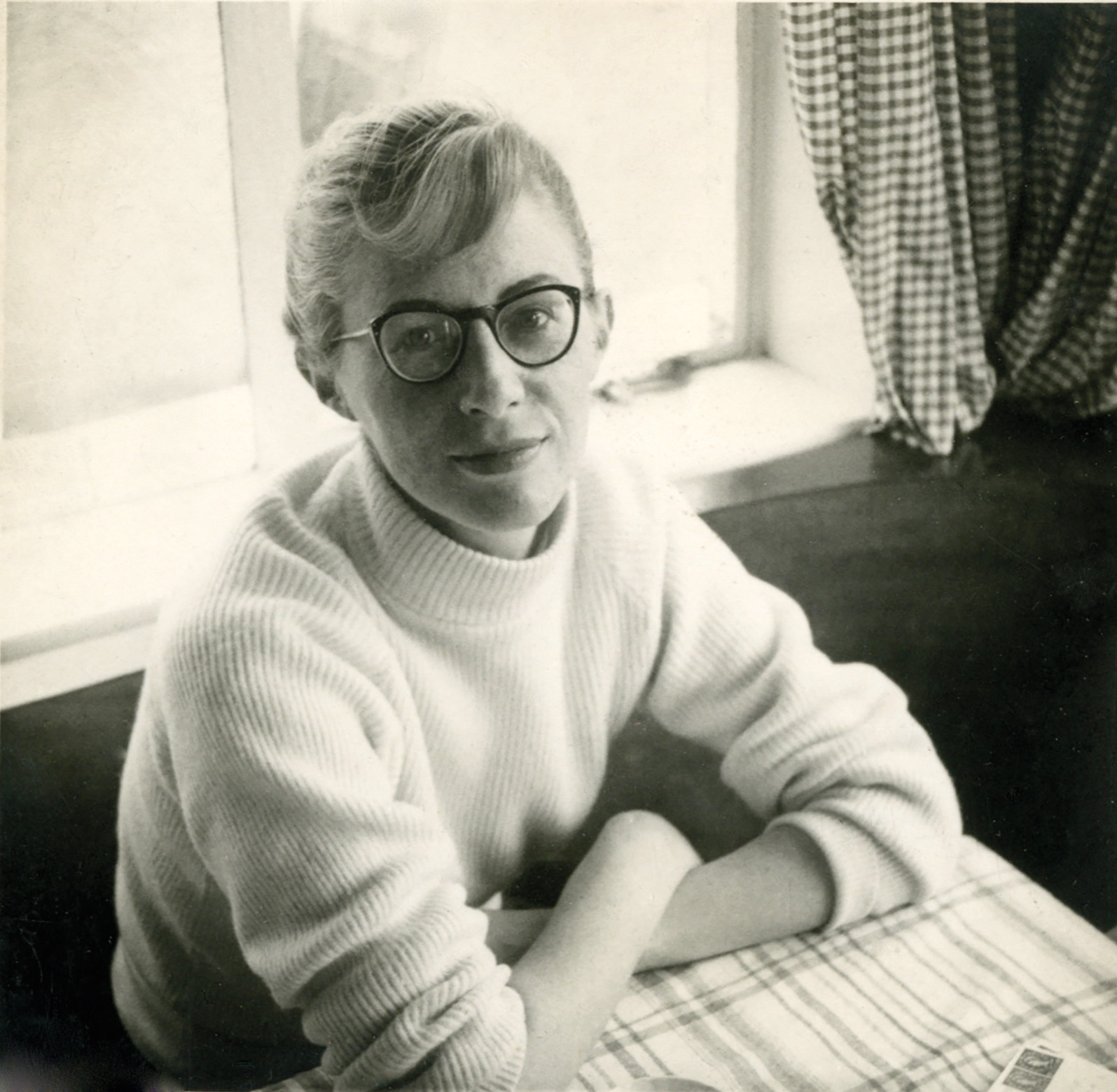

Monica, partisan and embattled, hated this expansion, agreeing with Kingsley Amis that “more will mean worse”. She remained stubbornly traditional in her faith in the role of lecturer, dedicated to the love of and the communication of great literature rather than to careerist publication and self-promotion. But, although somewhat old-fashioned and decidedly anti-modernist in her literary tastes (George Crabbe was one of her favourite poets) she was strikingly unconventional on the podium: “A touch of tartan when the topic was Macbeth: swinging pearls when it was Cleopatra.” These performances made an immense impression on the young Sutherland, as a fresher in 1960, who says that he would have “crawled over broken glass to hear them”.

Sutherland introduces himself fully as a participant about halfway through this memoir. He reveals that his original plan had been to tell more of his own story, but decided to leave the spotlight on her, “where it belongs”, leaving out most of the compliments she bestowed on one of her most promising students. This must have been the right choice. What he has given us has indeed salvaged her from the abusive caricatures of many who knew her, including Larkin himself, and many who knew her only at second hand. He has presented her in all the lively complexity of her prejudices and her fears, her courage and her wit.

***

The most damaging of those caricatures was created by Larkin’s friend Kingsley Amis, in Lucky Jim (1954). Larkin, Amis and Jones, three very clever, first class students, had all been at Oxford at the same time, during the war, and had all then been banished (in Amis’s grumbling view) to the dreary provinces. The version of Monica as Margaret Peel, a needy, dowdy academic spinster, was the version that first lodged in my consciousness, as a scarecrow alarming enough to warn any woman off the academic life. (I took it so personally that I was even upset by her name being Margaret.)

The portrait was inspired, as we know, by Amis’s visit to Leicester, and some details of Monica’s appearance and mannerisms were supplied by Larkin. The names Amis originally chose for her were close enough to invite libel action, and even when they were changed she and her milieu remained readily identifiable. What unforgiveable mixture of spite and insensitivity can have inspired Larkin to betray his friend, ally and lover in a way that would render her everlastingly ridiculous?

Larkin was at that stage an aspiring novelist himself, rather than a poet, and he was not to know that Lucky Jim would become a sensational and lasting success. The accounts of Monica’s bruising encounter with the novel, as she braced herself to confront it in bed, “beautifully arranged” in a nightdress, make painful reading. She poured out her response in hurt, indignant, erotic, impassioned but curiously stoic letters to Larkin.

Her ever-loyal mother wrote to her some editions later: “Mark my words that book will die.” But of course it didn’t. Its version of her endured, convincing readers that she was a woman who fancied herself in “a green paisley frock” worn with “low-heeled quasi-velvet shoes”, who had improbably ensnared poor Jim Dixon because of his “politeness, friendly interest, ordinary concern, a good-natured willingness to be imposed upon”. (As Larkin himself could have commented, in his customary epistolary diction to Amis, “Ogh! Argh! Gob!”) Philip Hensher, reviewing Larkin’s collected Letters to Monica in 2010, refers to the “venomous accuracy” of Kingsley Amis’s portrait and asks, rhetorically, who “can do anything but give thanks that they never dined with Monica Jones”?

But it wasn’t even accurate about her shoes. She always wore high heels, stylish ones at that, and was well known in later years for tripping along in them from the station to her country cottage by the rushing Tyne. (She never learned to drive.) She may have dressed flamboyantly and eccentrically, but Larkin loved her red suspender belts and the holes in her silken underwear and her principal-boy legs, and encouraged her to describe what she was wearing when she was writing to him.

Monica, writing to Larkin in the first shock of the impact of Lucky Jim, says, “K. would love to make himself believe that I am the sort of character who pretends to do in herself with sleeping pills and uses the wrong lipstick and dresses with fatal wrongness.” But Sutherland convicts Larkin himself, as well as Amis, of “double-dyed” treachery, and robustly comments that this was the moment “when she could/should have broken with Philip, and sued the backside off [the publisher] Gollancz, rendering Amis an untouchable author”.

[see also: A life more ordinary: salvaging Philip Larkin’s reputation]

But she didn’t break with Philip. She wrote him one of her letters. By this time they were already too deeply embroiled, committed to a lifetime of interdependence and to a long dying fall of alcoholism and ill health, marked by his half-cocked infidelities and her tenacious loyalty. (In one letter, intriguingly, Larkin suggests that his relationship with Monica “is a kind of homosexual relationship, disguised”: what can he have meant by that?) They were engaged in a kind of folie à deux, egging one another on in extreme and often unattractive attitudes: well-read people posing as philistines, enjoying The Archers, claiming to fancy the little bunny rabbits of Beatrix Potter and Racey Helps, playing infantile games, railing at immigrants, and pornographically defacing a novel by Iris Murdoch.

***

This last aberration reminds one of the folie à deux of Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell, who amused themselves by defacing the jackets of books from Islington Public Library. Their folly ended with a bang, not a long-drawn-out whimper, but their embellishments of the Arden Shakespeare and Agatha Christie have been put on display for public admiration, a dignity not likely to be afforded to the scatological Larkin-Jones version of The Flight from the Enchanter. Indeed, as Sutherland suggests, the woke generation that posthumously applauds Orton is more likely to hurl into the Humber the statue of Larkin that now steps out at Hull station.

During the first half of this memoir the reader is sucked down into a vortex of guilty Schadenfreude, as we eavesdrop on this odd couple tormenting themselves and one another with jealousies, rages, and vituperative attacks on their friends and colleagues.

She was excessively afraid of birds and burglars; he was morbidly afraid of death. They were both, according to Sutherland, “world-class malades imaginaires”. As we know, Larkin spent his whole life fearing death, a fear that inspired some of his finest poems. He was deeply exploitative, and selfishly indecisive, and he knew it. She wasn’t as afraid of life as he was, but she was often loud about her misery: after ten years at Leicester (where she was to spend the rest of her teaching career) she writes that she has wasted “my best years and nothing to show… You talk as though you’re as badly off as me till I believe it, but of course you’re not: you may be as miserable as me, but in the world’s eye you are a successful man… I don’t deserve the dignity of being miserable, ridiculous is what I am… a reject, an incapable…” How glad we are not to be them, not to be there, not to be imprisoned in their lockdown of complaint and paralysis! Reading about their gloom eventually elevates the reader beyond Schadenfreude into a kind of blessed exhilaration.

***

Their letters were their escape, their bond, their bondage. Thousands and thousands of words they poured out to one another, over the years, a correspondence that Sutherland compares to that of Héloïse and Abelard, to that of Swift and Stella. Their obscenities he relates to what Virginia Woolf called, in the Swift-Stella context, the “little language” of love, a lovers’ code that is a deliberate defiance of civilised and academic society. And we do know that Larkin was indebted to Monica for some of his insights, even for some of the words in his poems. He dedicated The Less Deceived to her, unambiguously, and “An Arundel Tomb” stands as a more ambiguous memorial to their mutual deceit and devotion, to their strange habit of taking “churchy” and churchgoing vacations in cathedral cities. A confirmed atheist, we are told he wept sentimental tears over his favourite hymn, “Lead Kindly Light”, when Monica persuaded the village silver band in Northumberland to play it for him.

The narrative changes pace when John Sutherland himself enters it in 1960, and we are suddenly presented with the living, breathing, pub-going Monica, fond of and flirtatious with “her boys”. She is very different from any of the epistolary personae she adopts for Larkin, and much more fun. It is a relief to find her, surrounded by admiring students, sociably sinking a few pints at the Marquis of Granby or the Clarendon.

John and Monica became good friends, eating and drinking together, and she spotted early that her new protégé was a “great boozer”. Sutherland has written candidly about his own problems with alcohol, confronted with the help of Alcoholics Anonymous years later, and he believes Monica spotted his predilection early, warning him not to get so “sloshed”. He managed to stay on the wagon for the vital five months before his finals, then lapsed. This makes him less judgemental about and more sensitive to her alcoholism, which became more and more pronounced, as did Larkin’s. But to her “boys” at this period, she was accepted as “a studiously good-looking woman, sharp on repartee, who bought her rounds… a conversationalist… amusingly indiscreet, with the ever-present tang of malice”. This doesn’t sound very like Margaret Peel of Lucky Jim.

But not long after these happy golden years, as Sutherland was later to discover, she was to descend into heavy solitary drinking, and into serious ill health. She was at last allowed to appear with Larkin in public, as his official partner, and to live with him, because he couldn’t manage without her. They did love one another, after their fashion, but it clearly wasn’t the kind of elevating love that most take the last lines of “An Arundel Tomb” to describe.

Andrew Motion wrote and published his biography of Larkin while Monica was still alive, and had to tread cautiously. Her “boy” John has done her a great service by posthumously rescuing her from Larkin’s abuse and Amis’s misrepresentation. This isn’t a dutiful feminist remake of an undervalued woman. It is a tribute to a real woman, who lived a real life. And who else could or would have told us that she “could play the kitchen range like Yehudi Menuhin”?

[see also: Philip Roth and the repellent]

Margaret Drabble’s novels include “The Dark Flood Rises” (Canongate)

Monica Jones, Philip Larkin and Me: Her Life and Long Loves

John Sutherland

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 288pp, £20

This article appears in the 21 Apr 2021 issue of the New Statesman, The unlikely radical