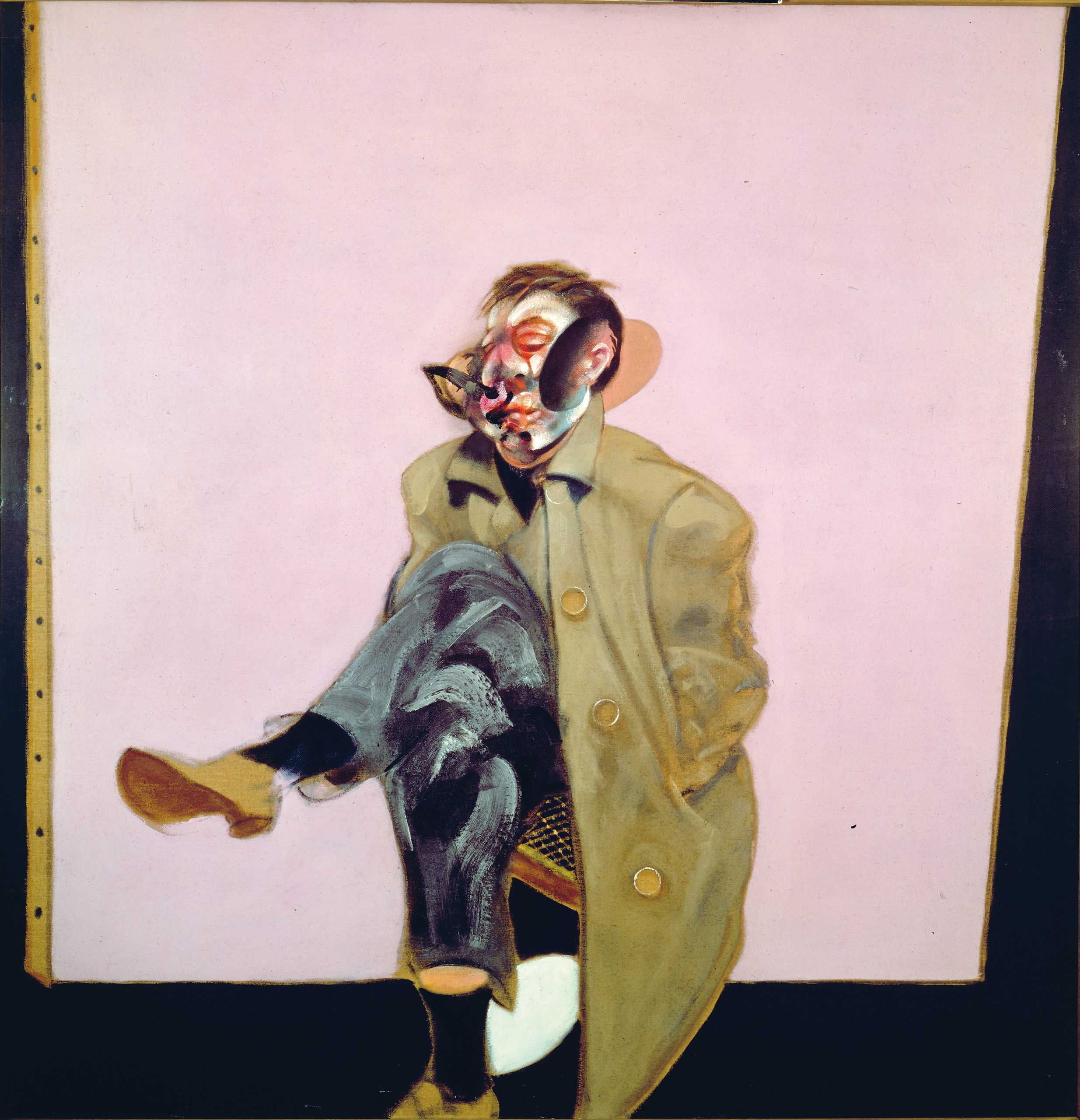

How great was the work of Francis Bacon? That’s the only question that matters, and it’s still a hard one to answer. Thirty years after his death, he hovers so large over British visual culture – such a vivid, garrulous, flamboyant, theatrical figure – that it is difficult to assess what he actually did, day after day, in the studio.

This large, generous book contains it all: the childhood whippings by his father’s servants, the adolescent flight to interwar Berlin and Paris, the thieving, the cat burgling adventures, the overnight fame, the gangsters, beatings, the postwar Tangier dives and the long-lost nights of Soho in its bohemian prime; the wild, hilarious, bitchy lunches at Wheeler’s – all those oysters, all that champagne – and, of course, the dramatic self-destruction of his two great loves, Peter Lacy and George Dyer, one by whisky and one by drugs. Too much!