In the first decades of the 20th century European modernism took many bewildering forms; none was odder, perhaps, than the linocut. There was, nevertheless, a logic to it since it was a medium without a tradition: unlike established printmaking – engraving, etching, woodcuts – working on sheets of lino was free from the lingering shadow of Dürer, Rembrandt or Goya. Lino, its adherents believed, was familiar to the wider public and therefore it was the ideal starter material – accessible, affordable and unburdened by off-putting high-art associations.

Linoleum was invented in the 1860s and artists in Germany started using it in the first years of the new century. However, it proved slow to catch on, and linocutting was not widely taught in art schools. In 1926 though, Claude Flight – a former beekeeper, army farrier and a friend of Henry Moore, Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth – was employed by the progressive, newly established Grosvenor School of Modern Art in Pimlico in London, to give classes in linocut printmaking. “Cutting Edge: Modernist British Printmaking”, an excellent exhibition of a long-overdue subject at the Dulwich Picture Gallery, shows how Flight and a small group of fellow teachers and students – notably Sybil Andrews, Cyril Power and the Swiss artist Lill Tschudi – transformed the idea of what this most quotidian of materials could do.

Whence and Whither? by Cyril Power, c 1930

Flight believed linocuts should be “an art of the people for their homes”, so he and his Grosvenor School colleagues didn’t look far for their subjects. They chose familiar themes suitable for a new medium and a democratic audience: commuting and work, sports and funfairs, music and food. The artists may have had populist aims but their prints were not cheap, costing one to three guineas – a middle-class week’s wages. In many ways the closest equivalents of the linocuts were the woodcuts of the Japanese Ukiyo-e printmakers of the 19th century, the likes of Hiroshige and Hokusai, who also presented a stylised version of everyday life.

Because it is easy to work, lino is perfectly suited to curves, and the Grosvenor artists developed a rhythmical graphic style ideal for what Flight called “the speeding up of modern life” and for experiments with cubism and futurism. The artists married the bustle around them with the design ethos of art deco and the colour and movement of jazz. Despite their international outlook, this is nevertheless a very English show. Tschudi’s skiers and bobsledders are rare whiffs of the non-native here.

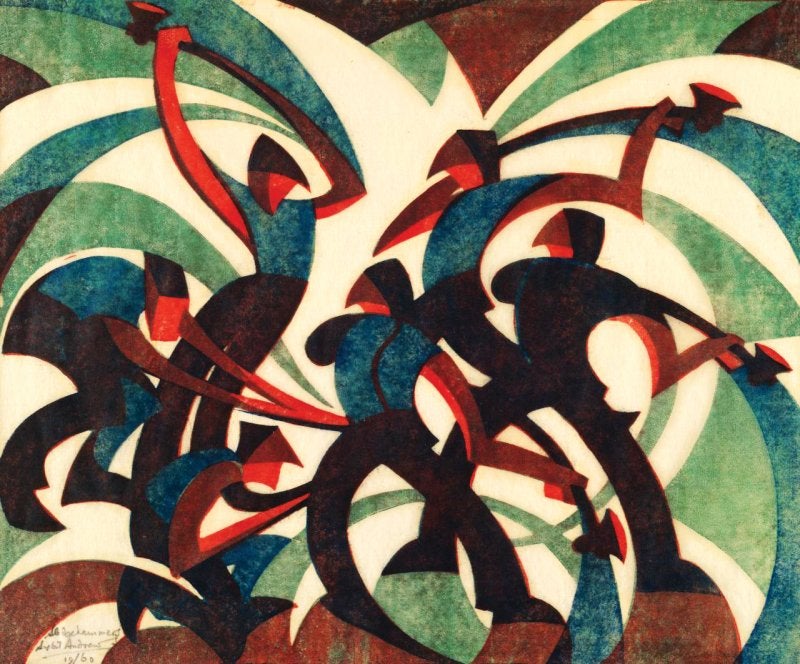

Sledgehammers by Andrews, 1933

For all the inventive brilliance of Andrews’s images of speedway racers or Power’s whirling vortex of a merry-go-round, the linocut could also be used to show alienation and the anonymity of modern city dwellers. Power made something of a specialism of it. His c 1930 Whence and Whither? shows an unsettling crowd of commuters descending an escalator in packed but perfect, mechanistic unison – a snapshot straight out of a Fritz Lang film. In The Tube Staircase, 1929, a spiral stairway is empty of people largely because it looks like the central screw of a mincing machine.

Andrews, a devout Christian, also demonstrated something of the linocut’s ability to work outside usually joyous communal realms. In Golgotha of 1931, she produced an image of Christ on the cross. Full of jagged diagonals and triangles, with blood red as the primary colour, Christ is as much electrified as crucified – this is CRW Nevinson’s war paintings of exploding shells repurposed. Power made a print of the murder of Thomas à Becket at the same time, but the curves of the slashing blades look merely decorative by comparison.

Speed by Claude Flight, circa 1922

Power and Andrews met in Bury St Edmunds shortly after the war and decided to form an artistic partnership and move to London together: he was 46, married and with children, she was 20. It is not clear whether their relationship was romantic, but its real fruit was a series of eight posters for London Transport, commissioned by its visionary director Frank Pick, which they signed as “Andrew-Power”. With extraordinary panache, these invited the viewer to use buses and trains to get to Lords, Wimbledon or the Derby. Although they are lithographs, the posters use the same novel stylisation and reduced palette that the artists had pioneered in their linocuts, and they are proof that public art could be both radical and successful.

The Grosvenor linocuts were widely exhibited and critically acclaimed, but their heyday lasted for only a decade. By 1937 Flight had produced 64 of his 65 known linocuts; Tschudi returned to Switzerland; Andrews emigrated to Canada in 1947 and the extraordinary flowering was over. Oddly, none of the main figures amounted to much in other forms of art: their exceptional talent was reserved for lino.

The exhibition runs until 8 September

Cutting Edge: Modernist British

Printmaking

Dulwich Picture Gallery, SE21