Between January and March 1961, the historian and diplomat Edward Hallett Carr delivered a series of lectures, later published as one of the most famous historical theories of our time: What is History? In his lectures he advises the reader to “study the historian before you begin to study the facts”, arguing that any account of the past is largely written to the agenda and social context of the one writing it. “The facts… are like fish on the fishmonger’s slab. The historian collects them, takes them home and cooks and serves them.”

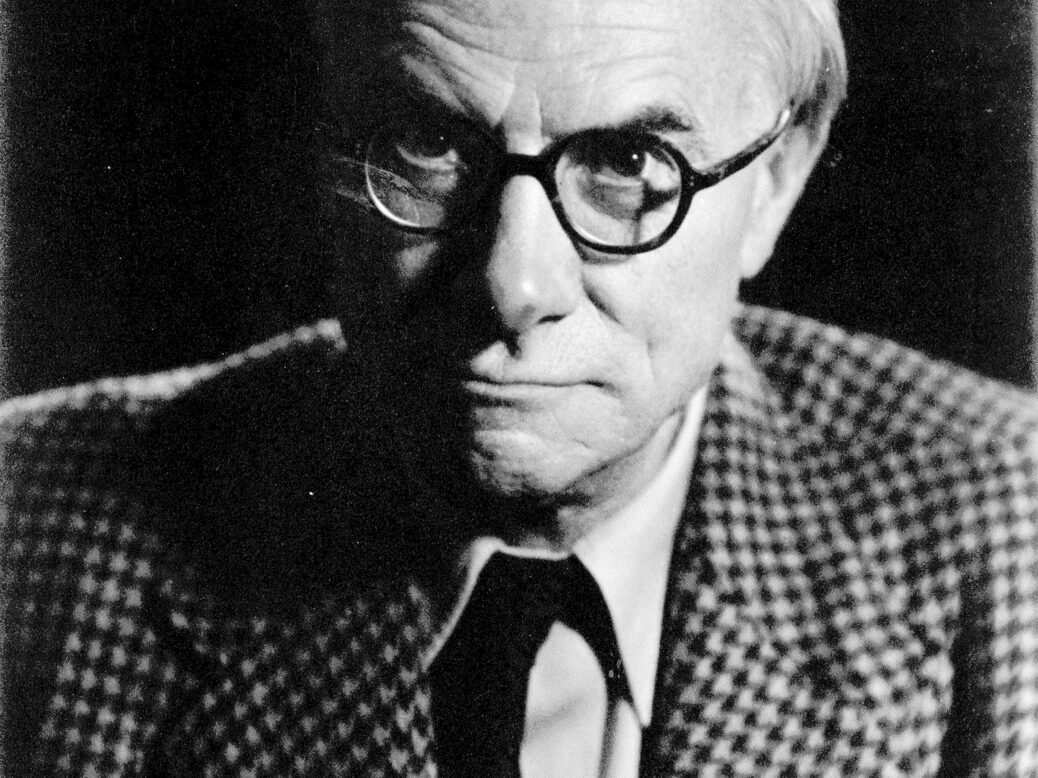

My childhood memories of history and the learning of history were enhanced by the omnipresent familial legacy of my great-grandfather, EH Carr, nicknamed “the Prof”. He was the sort of man that always had holes in his sleeves, ate milk pudding every night and loathed fuss. Despite this, he was highly revered, so much so that my grandmother would dust the house plants prior to his arrival. He died six years before I was born, but his energy lived on within our family and encouraged my insatiable interest in history. As I rolled out my family tree on my grandparents’ living-room floor and closed in on the name Edward Hallett Carr I began a lifelong interest – and an imagined dialogue – with my great-grandfather.