The Man Who Fell From Grace has a name, but it’s not important. What’s important is the “Only God Can Judge Me” tattoo on his ribs with praying hands and rosary he referenced whenever he erred. What’s important is the way he laughed when he lost hand after hand after hand at Texas Hold ‘Em and blamed me for his undoing. What’s important is the way he flipped me on my stomach with unsettling finesse when he wanted a good fuck.

What’s important is how beautifully, how masterfully he called me a cunt, as though he made the word specially for me.

When I first met him, the man I’ll call E, I was 17 and he was 24. It was at one of those Hollywood nightclubs run by middle-aged men in cheap suits who were more than pleased to slip underaged girls in for a price more tawdry than money. And though I don’t want to remember that night, I do. Again and again I replay those long swinging strides he takes toward me and brace myself in memory. Maybe, in the ten years since, I have conjured it too many times to forget. In remembering, my mouth curls upward, almost happy, then swiftly down again, because I know how this story goes. I created it.

A photograph from that night shows I wore a bright yellow dress, my brown curls hanging glossy against it, my skin burnt but ruddy from having spent so much time in the sun. Flanked by two of my best friends, I look happy and healthy and remember being both. A decade on, I can’t help but feel a desire to grab the girl in the photograph and tell her what the next week will look like. The next month. The next year. Forcibly, because she will no doubt kick and scream, take her away from it all. But then anger subsides, and I realize that what I really want to do is just stand beside her and tell her that life is about to get a whole lot tougher. That she will suffer, but she will survive. And I want to stand back and watch her do it.

I’ve loved once, twice, maybe three times, but never did hope disfigure me as deeply as the first. Never was it as unruly and wild as it was with the Man Who Fell From Grace. Ours is a story not dissimilar to those who followed The Oregon Trail, so parched for what the West promised. So parched for goodness in perpetuity.

I started to wonder if it was maybe California that did it to us. Maybe it was the mythos of the West that drove us mad. All those stories of self-made men and Protestant work ethic and triumph and riches, told us so many times we thought they were ours. Victory, we were certain, was our birthright. Maybe, then, it was the sun that spoiled us. Maybe all that nature, so varied and bountiful, made us feel richer than we were.

Or was it our parents, because isn’t it always? Maybe the dogged desire to prove ourselves worthy, not just of their love, but of the American promise they represented, deformed us. Maybe we just wanted to be seen, remembered, and were searching in all the wrong places, doing all the wrong things, lashing ourselves repeatedly in the name of it, antiheroes of our own twisted narratives, forgotten in the rubble of our own ruthless longing. Maybe it was so many things.

Just like Dad and Grandpa, I am a Californian; all of us children of the American folklore that is as much our reality as reality itself. And in us live those who preceded us. The millions who fled Westward in search of prosperity, convinced that once they reached this Edenic land their problems would be solved; happiness, harnessed; and tragedy, thwarted. And just like Dad and Grandpa and so many others, in me survived the pioneering spirit of the West and all its attendant delusions.

With E, the Man Who Fell From Grace, the man I loved first, I hoped despite myself. And though I did not see it at the time, in him subsisted the same yearning, the same fallacies, both of us hoping the chaos would be the precondition for some kind of redemption. And with this hope, secrecy and deceit were spawned, integrity and grace laid to waste in their wake.

Here is the American Dream eviscerated, its underbelly unearthed. Here is how people become the people they hate.

****

The first casino E took me to was Hollywood Park, back when the racetrack was still intact and the salmon pink facade with neon signage and warped-glass block plinths loomed, a vestige of a golden age. But what once stood testament to human ambition and high-rolling glory had tarnished, assuming the aspect of something tragic. Maybe once it was a bastion of hope, but in 2007 the subprime mortgage crisis changed all that. It felt like desperation. It felt like the end of everything.

“He’s on tilt. You should try to get him away from the table. Son of a bitch’ll lose everything he’s got,” said the large, broken-hearted-looking man next to me. E’s winning streak had ended, and he had started to overbet to compensate for his growing deficit. It was my first time at a Texas Hold ‘Em table and I didn’t know what on tilt meant, but I gathered from the man’s tone that it was not a good thing to be on. So after considering, and ruling out sitting there and waiting for the bad thing to happen, I did what he suggested.

“Hey,” I said, nudging E as playfully as I could, “I’m getting pretty tired. What do you say we go back to yours? Watch the game and smoke a joint?”

He stared at me, pausing for what seemed like too long, then let out a granular, ruined laugh I hadn’t yet heard. “Aren’t you having fun, hon?” he asked, wrapping that long, brawny wingspan of his around my shoulders. His smile, broken with yellowish teeth.

“Sure I am,” I said. Scared. Lying.

“I’ve got a little favor to ask you. I don’t have my debit card on me and I’ve used up all my cash. How about you spot me a little, I win back all my money and then some, and I spoil you. Take you out to a real nice fancy dinner. You’d like that wouldn’t you, hon?”

I’d like that wouldn’t I. I mumbled the words to myself, hopeful and nervous, feeling very much like I had little choice in the matter. Like it was no longer up to me.

“What’d you say?” he asked, lifting my chin up affectionately. Appraisingly. His eyes, large and searching.

“I’d like that.”

The large, broken-hearted man grimaced. He’d seen our type before and knew where we were headed and how we were going to get there. But he had his own burden to carry, like most of the folks in there. So on the game went, until E squandered it all, like the man said he would. When E asked again if I had more money, I shook my head, the imperious eyes of my parents behind me, my own looking straight at his.

He knew I was lying, and he wasn’t going to let me get away with it.

****

Shortly before I met E, shortly before high school graduation, Dad called to say he had something to show me in the garage. Gray-haired and grinning in a suit, he stood, arms stretched exultantly, beside a brand-new silver Mazda. His whole being flushed with the pride particular to fathers who can not only provide but spoil.

He was both triumphant and wistful as he handed me the keys, not fully knowing what he was granting me access to, but accepting that his time as gatekeeper was coming to an end. That he would continue to be Dad, but in another iteration. Soon, too, I would be gone, and Mom and Dad would have to go back to being the people they were before I existed; I would have to be something else entirely. And what then? What would life look like then?

I learned, that day in that new car with its sterile smell, Dad’s sad face beaming beyond the window, how freedom can suffocate. How it can instill a fear so great it nearly paralyzes. Silently, I looked at the concrete wall cracked with headlight glow and considered my future, limply fanned-out in front of me, the engine humming and the steel body that housed it, inert.

That car facilitated more than I anticipated, as my coming into possession of one coincided with E’s loss of another. I remember how his had looked sitting in front of my parents’ building: this big black buffalo with yellow eyes; a Lexus the size of a cruise ship. And I remember the swish sushi restaurant in Hollywood it took us to for our first date, where E put that long, brawny wingspan of his around me for the first time. Where he told me I could get anything my little heart desired. Where I began to cut corners in my mind to convince myself of what I thought was his godliness.

One week later, he smashed that Lexus into the median strip of the 101 freeway in the middle of the night, totaling the car and, in a way, his liberty. When I recounted what little I knew of the incident to Dad, he got litigious about it, putting his lawyer jargon to good use, urging me to stay far away. But, defiant with the rebellious streak of teenagehood, I decided my mission was to find holes in Dad’s conviction. Take his assumptions to court and destroy them on cross. E was a good man and he would love me and Dad would have no choice but to admit to his wrongness.

And so maybe my time with E was never about E at all. Maybe it was about freedom. Maybe it was about the freedom he lost and the freedom I gained and what I chose to do with it, which was this: I gripped my hands on the steering wheel Dad gifted me and let E backseat-drive, barking at me to go here and go there and not make a fuss. Because what did I have to make a fuss about? I wasn’t alone, and that was all that mattered.

****

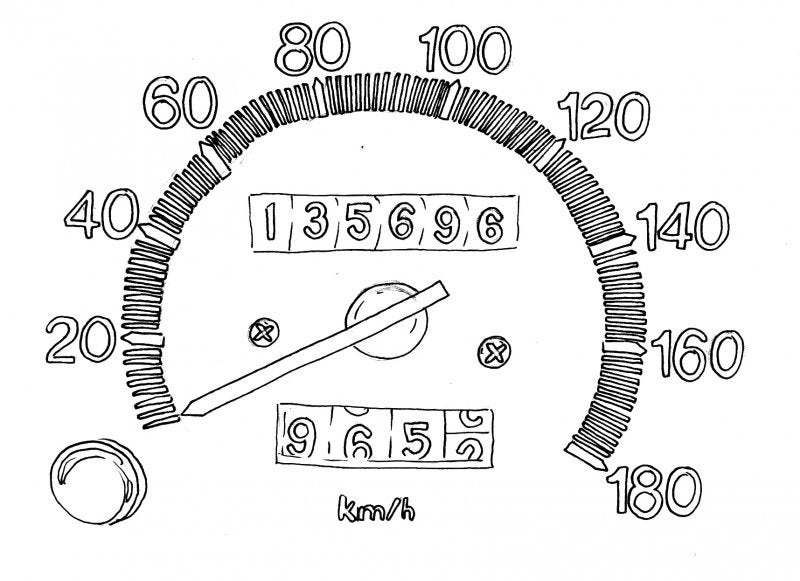

It didn’t take me long to attune myself to the casino and all its working parts. The people, the glossary of terms, the comps, the security brigade, the incessant C-tone drone of the slot machines, the swift and deliberate hand motions of the croupiers, and the allure of the high-stakes poker room, which E always kept in his periphery should he win an exceptionally robust pot.

I also learned a great deal about tilting. And once I did, it was everywhere, bursting from its uprightness, demanding to be noticed wherever I went. But the tilting I paid most heed to was the tilting in my Man Who Fell From Grace. How he’d unspool at the poker table and come undone in bed. How he’d grow worn with wanting in the night and senseless with needing in the day. Maybe it’s not so bad to be on tilt, I thought, as though it needed to be forgiven.

One possible origin of on tilt, as it’s used in reference to poker, can be found in the world of pinball machines. If you’ve ever played one, you know how it feels to watch your last steel ball sink into the drain. And if not, you can imagine it: hours have passed; your winning streak is intact. A crowd gathers around you. You’re indomitable, you think. And then, it happens. You see it in slow motion: the ball heading down the groove that leads to the gap between the flippers. Adrenaline surges.

In a desperate effort to rally, you try to shove the machine to push the ball back to safety. But you push too aggressively; the machine flashes “TILT” on its screen, freezes its flippers, and the ball slides to its death while you stand there, wondering how much of your failure is a residue of your own design and how much is a product of the world conspiring against you. You stand there and you watch it and you know that no amount of clawing or bellowing will bring it back. You know it and ruins you.

In the world of poker, though, the stakes are a lot higher than a ball. They’re your life savings. Your house. Your family. Your humanity. And the player isn’t just trying to tilt some plywood and metal parts; they’re trying to tilt the whole world and they’re furious and they’re blind.

****

In the beginning, we stuck to California’s casino circuit: Hustler, Hollywood Park, Commerce et al. When my parents asked me where I was headed, I lied. I had a roster of friends whose names I’d rattle off if they wanted specificity, but I mostly just said “out” and they took my word for it. As the miles on my car started to rise, though, the lies had to become more elaborate. Mom wouldn’t think to read the odometer, but Dad became increasingly suspicious, interrogating me the way he would a defendant.

“Are you going to eat dinner with us?” he asked on one such occasion. I was carrying a duffle-bag of clothing and a stack of textbooks; accustomed to the long periods of time E and I would spend at the casino, I learned how to best fill them.

“I’m not hungry.”

He peeled his eyes away from the television, clocking the bag and books. “Where are you going?”

“To Jennifer’s.”

“What do you two have planned?”

“Not much. Maybe watch a movie.”

“Don’t you have homework to do?”

“That’s why I’ve got my books with me,” I replied, disproportionately defensive.

“You’re looking very skinny.”

“So? What is that your business?” He was right. I was all bones.

“Well, I guess I care about my daughter’s well-being. Crucify me if you must.”

“My body, my way.”

“Don’t forget why you’ve been granted this freedom in the first place. I got that car for you to use for good. For school, work. Not to aimlessly gallivant with.”

“If I remember correctly, no moral stipulations came with that car,” I hissed. “If I knew you’d use it as a bargaining chip, I never would have accepted it.”

“You’re a mess.”

“Fuck you.”

He laughed, locking eyes with Mom, his compliant ally, and sipped his lager. “It would behoove you to not bite the hand that feeds you.”

“I feed myself, man.”

Again, he laughed. “Where do you think all that toilet paper comes from? Your limitless supply of toothbrushes? The fridge full of food? How about that, man?”

“I’m leaving.”

“Get an oil change for that car. And grow up, will you?”

I slammed the door, the sound following me down the hall, into the elevator, and into that car of mine, my muddy morass of bail-bond paraphernalia and Newport cigarettes and balled-up fast food bags that I got to calling home.

****

Mom and Dad together were the three principal gods of Hinduism: Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva. The creators, preservers, and destroyers of my universe. They were everything. And in their everythingness, they provided me with an idyllic Southern Californian childhood of miniature trains, weekends in Palm Springs, and trips to Disneyland. Dad would lift small me onto his shoulders, and we would explore the sun-bleached terrain together like pioneers of the Wild West, his sinewy runner’s legs leading while Mom followed with her big red smile and disposable camera. Dad really did love large, and Mom always matched him in her good, maternal grace.

But Dad, I would later learn, had a black dog scratching at his door. This is the metaphor he used for his depressive episodes, and a metaphor I would adopt in adulthood when I would feel a similarly inexplicable sadness – but it wasn’t inexplicable, really. Grandma Pearl, his mother, was bipolar and Grandpa Barry, his father, was seized by delusions of grandeur, both of them propelled toward madness by the American Dream. So seemingly graspable. So seemingly reasonable. We were the progeny of this, but we talked little about the pain he carried and less about the pain he passed down to me. It wasn’t until I left home that I realized who he was, and what parts of him were also parts of me.

It took me a long time to accept my parents as flawed human beings. To realize that they, too, lived and suffered. That they too were products of their past, scored with impressions too subtle, too embedded, to fully understand how they manifest in the living moment. From this came the understanding that there is no such thing as an unbridgeable gap between the good and the evil, the strong and the frail. That for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. And that, if patient enough, the reasons for things so seemingly incomprehensible will become so apparent, so logical, as to astound.

Now, when I remember how Dad hurled that backpack across the room at me when I was seven, I think about how Grandma Pearl used to wait in dark rooms for him to come home so she could beat him. And when I remember how he rubbed chicken in my ear in front of his friends – punishment for a reason that eludes me now – I think about the love he sought as a child and only rarely received.

And when I remember how Dad clubbed me with that shoe, and splotches of blue and purple and charcoal appeared, I think about the incalculable brunt of existence he had to endure and how, though I wish he did a better job of reigning in his temper, he tried his best to love me. And he did. In his own imperfect way, he did.

****

Every month with E brought a new disaster, each more novel than the one preceding it. Like the first time he landed himself in Downtown Los Angeles’ Metropolitan Detention Center. When I hadn’t heard from him for a week, I reached out to a friend of his I had met at the dingy office space where he worked with E, 30 miles from downtown LA near Cheeseboro Canyon, former home of the Chumash Indians.

A popular terrain for bikers, equestrians, deer, and bobcats, the canyon lies in stark contrast to the suburban panoply just outside it. The American West lobotomized, its horse-riding frontiersmen turned into Starbucks-guzzling hustlers. I would drive E to the office a few mornings a week, grabbing some breakfast from McDonald’s, fucking in the back seat, listening to The Game or Lil’ Wayne or T.I., our morning breath filling the car.And sometimes when I picked him up, he’d invite me inside, where there was a fleet of Dell desktops, a water cooler, and an indoor putting green.

Their modus operandi was founded on profound misinterpretations of Glengarry Glen Ross and Boiler Room, two films they watched repeatedly. “Always be closing, baby!” E would shout, clapping his hands, chest puffed out, parading around the office like some New York City titan when he was, in fact, selling accounting software to small business owners in a nobody town in California.

“Anyone who tells you money is the root of all evil doesn’t fucking have any,” he’d say, aping Ben Affleck in Boiler Room. “They say money can’t buy happiness? Look at the fucking smile on my face,” he’d cry, skipping to the whiteboard where they kept a monthly tally of accounts, and his co-workers would nod and smile and high-five him, all of them certain they would become millionaires like in the movies, all of them a dark, rich shade of machismo.

It was E’s office friend who told me about the Federal Bureau of Prisons’ inmate locator. When I reached out to him after I hadn’t heard from E in over a week, he invited me to his parents’ house on the outskirts of celebrity-infested Calabasas, where Ferraris idle by shopping centers and stilettoed women preen and bloviate before scratchless mirrors, tongues slithering beneath the repose of botoxed faces, their limbs long and wanting.

E’s friend did not belong to this society, though. None of them did. They were the motley crew that had no qualms about fouling it up, exhaling smoke and cackling like hyenas. They belonged to something else entirely: a league of pink-collar workers who prayed to a pink-collar god. Would throttle a friend for one more line of cocaine, drink themselves motorless for one more Lakers win then stumble back to the house of parents who had long since given up on them; on themselves.

When I arrived, E’s friend snuck me in through the dark garage into his bright white bedroom and motioned to his unmade bed as he turned off the lights. There, on greasy sheets, our shoulders brushing, he pulled up the inmate locator, pointed at the “Find By Name” tab, and told me what to input should I want to find him. Then he told me E didn’t deserve me, that I was beautiful and young and full of promise, as he slipped his hand between my thighs, the laptop screen glowing on our faces. I pushed his hand aside, told him I couldn’t, and left, making sure to thank him so he wouldn’t speak badly of me to E.

I did not want anyone to speak badly of me to E, so I did what I thought needed to be done. Like the time I stayed up late drinking whiskey with him and his roommate deep in the folds of the Valley, the two of them on either side of me, wide-eyed and hungry. They guided me toward the spare room with the flatscreen and king-sized bed, where I laid myself down, spreading my legs as though on an obstetrician’s table.

When E walked out and left me with his roommate, I tried my best to make him proud. I wanted to show that I was the girl who didn’t ask for too much. I needed his approving gaze to lend corporeality to my being, just like I needed Dad’s approval to lend credence to my existence. His roommate made a few advances, which I met with limp body and slack mouth, and he pulled away.

“How could he do that? Leave me here with you?” I asked, incredulous.

“He just wants us to have a good time,” he said, a sticky-warm hand on my back, almost brotherly.

I was so very good at confusing wanting for needing, at bending to a variable will, razing integrity and morality on my path toward it. But this time, in the spare room, was too much, and I struggled to keep my body from crumpling into the blankets forever as though that would cover the shame. As though that would erase the time and space between the moment that I had met E and the moment I was in.

“He just doesn’t care. I mean nothing to him.”

“That’s just how he is. He cares about you. Trust me.”

I held those words as though they were holy relics. Repeated them to myself with the cadence and vigor of a martyr reciting incantations.

I had to find him.

****

E landed himself in prison multiple times in the two years of our relationship, so I got used to the inmate-finder and bail bondsmen and his father, who came to know me as the girl who was always around, catering to his son. Out of convenience, he used me as a point of contact; I was an exceedingly reliable one, desperate to impress everyone in his life so they would have no choice but to testify to my worthiness.

“You seen E?”

“He’s at the Detention Center.”

“For what?” he’d ask, exasperated.

“I’m not sure. Some kind of outstanding fine?”

“That boy ain’t never gonna learn. You know how much money he owe me?”

“I don’t.”

“Thousands,” he’d say, elongating the vowels. “I can’t even count no more.”

I never knew how to respond.

“He pay you back yet?”

“Not yet.”

“Man. He really coulda been somebody. Had a hell of a swing in high school. Hell of a shooter too. Can’t believe he done gone and wasted his goddamn life. My son. A loser. How’d that happen, huh?”

“He’s trying his best,” I said plaintively as though he were my own father and I needed him to know I was doing the same.

“Dad a former Dodgers player and sister in the WNBA,” he’d continue, uninterested in what I had to say. “He come from sports royalty. How does this shit happen to my own son?”

A fire raged in E, flames licking his sides, smoke spiraling around his neck and into his nose, asphyxiating him. Everyone in his life just stood there, motionless, watching him burn; marveling, I was certain, at the bravery of the girl who leapt in to save him. I was never able to meet the man his father told me he was or could have been, but I was so certain he was luminous and full of grace. So certain he was there, inside him, burning alive.

****

I remember the tabs from that first time: First name, middle name, last name, race, age, and gender. I knew I didn’t want to visit him in prison as that would be too much of an intrusion, so I marked his court date in my calendar, which I noticed was on his birthday, and waited for it to arrive as though it were our first date. I remember exactly what I wore: a white silk blouse with ruffles, high-waisted jeans, stilettos and a floral headband. I wanted him to know what he meant to me.

I was already familiar with the layout and proceedings of a courtroom because of Dad, who was a trial attorney. When I was a kid, I’d sit in the gallery watching him litigate beyond the bar where all the important players were: the clerk; the court reporter; the judge; the defendant; their counsel; sometimes a jury. Dad was his best self up there. In that courtroom, I began to understand his power and how others perceived him. Pride no sooner arose before it dissolved into fear. When I went to E’s hearing I felt Dad there, reproaching me for my stupidity.

Looking back, I traverse decades and centuries to understand. There is Dad as a sheriff in a bowler hat and suit pitted against E as a lawless gambler in a frock-coat and bolo tie. My father, upholder of justice, defender of the Constitution, and E, an avatar of roguish, deviant American individualism. Both of them righteous, both of them byproducts of the absurdity of idealised Americanism. It is easy to make sense of things this way. To dichotomize.

When I saw E, handcuffed in a khaki jumpsuit, spot me in the gallery, my anticipation was immediately replaced by shame. Whether he laughed out of happiness or incredulity I don’t know. But I know what it felt like to mouth “happy birthday” and hear nothing in return. I know what it felt like to smoke a cigarette afterwards, alone and confused. I know what it felt like to do exactly what I knew I shouldn’t if I was at all interested in survival.

And I wasn’t. What I was interested in was doubling down.

****

It didn’t take long for E to tire of California’s casino circuit, so he set his sights on more exotic locales like Las Vegas and Laughlin. Though I must have forked over thousands of accumulated dollars to fund his gambling habit and his expensive taste in sushi, the allure of comped flights and food and hotels convinced me he was not the louse his father, or my father, said he was.

I didn’t understand that these comps were part of a gambit devised by the casinos. I didn’t understand that the enterprise was kept afloat by people like E, insatiable and ill. Las Vegas, that shimmering Babylon of the West, all steel girders and glass pushing against that arid neverending nothingness of the Mojave desert, weighed heavy on their backs, crushing them.

When I was a child, Vegas was lazy-rivers, slides, jungle gyms and virgin coladas. It was Mom bringing chicken tenders poolside, my toes puckered from hours in the water, the warmth of her sun-soaked cotton against my cool skin. It was evenings in The Fremont Street Experience with Dad, all polyester T-shirt, cargo shorts, and New Balance tennis shoes, holding my hand and guiding me through five blocks of technicolor glow against blackening sky.

It was the clank of coins hitting metal trays from the depths of Glitter Gulch, its neon cowgirl presiding over us like the goddess of cheap thrills. It was skipping down the MGM Grand’s Yellow Brick Road, which wove its way through the casino to Emerald City, where the Tin Man, Scarecrow, Dorothy, Cowardly Lion, and Toto were waiting for me to join them, Mom and Dad behind me, arms around one another.

“It looks fake. I like it,” Dad would say each time we careened down the I-15 and the first contours of the city became visible. Though we spent countless holidays there, each time I saw it, warped and wavy from the pollution and heat, felt like the first time. And it felt like the center of everything. The one place in an otherwise unforgiving universe where air conditioning was in endless supply, slides never ran out of water, and no one was ever sad.

The Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas sign played a pivotal role in this illusion. When it was erected in 1959, nearly 55 years after the city was founded, its flashing incandescent bulbs and eight-pointed neon star were not only meant to embody the city’s burgeoning opulence, but to assure visitors they had reached the Promised Land.

In the 1990s, Vegas attempted to become more family-friendly, and it was during this permutation, crafted by publicists and architects, that Dad, alongside droves of other dads, decided this would be our getaway city. Vegas, it was implicitly agreed, was where we could be the people we could never be at home. Where we could slough off normal, rid ourselves of constraint, and be free. Wild. American.

****

In 2003, a new permutation began when an ad agency concocted one of the world’s most successful marketing campaigns: “What happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas.” Those seven words helped drive millions of people, even in the midst of the recession, to imagine the new versions of themselves they could be here, the problems they could elude and the vices they could indulge, free from judgement and consequence. Or so they thought. Their secrets, they were told, would be safe with Vegas.

E was one of these who found themselves defenseless in the face of such a declaration, spellbound by its lure. And for a brief period of time, I felt the same. How could I not? At the time, I didn’t realize that what happens in Vegas not only leaves Vegas, but stalks its perpetrators no matter the distance. So when E implored me to come, eyes bright with what I thought was the prospect of me joining him, I did.

As we drove down the I-15 in the middle of the night for the first and only time, Vegas revealing itself to us in the distance, I did not feel free or happy or loved, as I had when Dad, Mom, and I had driven down it in those early mornings. With E passed out next to me, crumpled grease-paper in his lap, a cigarette behind his ear, I felt alone. It looks fake, I like it, I said to myself, summoning the Vegas of my childhood and trying to superimpose it onto the glittering graveyard I saw ahead.

When we arrived, E finally awake and alert, the loneliness slunk sideways and made room for excitement. Maybe this will be different, I thought as we pulled up to the Imperial Palace valet, E straightening out his spine and using his large, coarse hands to smooth out the creases in his shirt. Maybe this time we’ll win.

“Welcome to the Imperial Palace,” said the man, a look of plastic cheer on his tanned, tired face, the din of bellman’s carts and shrieking women and slots nearby. The Promised Land.

In its first incarnation in 1959, Imperial Palace was the 180-room Flamingo Capri motel, located adjacent to the Flamingo Hotel where Dad used to take Mom and I for holidays. Then, in 1979, a few years after the completion of the 650 room Imperial Palace Tower, the Capri reopened as the Asian-themed Imperial Palace. It was a place with which I became intimately acquainted in the three days I spent there with E.

In its inherent perversity and get-rich-quick leaning, the casino is a beautifully American institution. Though there are widely varying aesthetic arrangements, they are all propped up by the same basic blueprint; not much, in fact, has changed since they started to sprout alongside towns in the 19th century, though as the towns prospered, primitive sporting shanties became ornate palaces. And the men came in droves, leaving the stability of the East for the purported fortune of the frontier.

And still, the men come in droves. Hope disfiguring, just like it used to. Just like it always will.

****

The first few hours at the Imperial Palace’s Texas Hold ‘Em quadrant seemed terribly lush. Though I had spent hours scuttling through casinos during childhood, hovering near Dad with bated breath as he pushed buttons and pulled gleaming levers, I had never been granted entry to this corner of the gambling universe. It was intoxicating: the tiki drinks, the colorful chips, the contemplative silences broken with triumphant roars. And E was the locus of its centripetal force, always good at making it seem like opportunity and luck would never run out. For this, people loved being around him. It made them feel good. But it made them feel even better when he went to pieces.

Whenever E would first waltz into a casino, he was treated like a dignitary. His towering, six foot four frame demanded it. But when he started to lose, the blighted child inside of him emerged and the hostile reverence in the other players’ eyes would quickly turn to smug pity.

Until then, though, he was on his best behavior: a model specimen. So when he told me he only wanted to play an hour or two before bed, I tried to think nothing of it. He looked so balanced and in his element, and I didn’t want to interfere with his precarious order. What could go wrong in an hour or two, I asked myself, as though misfortune was predicated upon length of time.

“Take this money and hide it in the room. No matter how much I want it, no matter how many times I ask for it, don’t give it to me. Ok?”

“Ok,” I said, nodding my head, his loyal lackey.

When I returned, I looked at E in the distance and tried to decipher his resonance. Familiar with his assortment of smiles, I was already dreading the one that I knew was coming. The broken one. Nevertheless I strode forth, buzzing with independence.

Like so many times before, I read. Intermittently, I would glance at E’s hand and try to suss what it signified. I scanned the other players’ faces too, making sure to keep my own as deadpan as possible in case I gave away his hand. The safest option was, for the most part, to keep my head down; if E felt as though I were responsible for thwarting his luck, he wouldn’t let me forget it.

Hours passed, hands were won, and wisecracks exchanged. A camaraderie developed among the players and it was so exhilarating to watch that I found myself hungry for it, craning over E’s shoulders to feel part of it. Then, it happened, and it took no time at all for me to register the shift. To sense that the world had tilted.

“Where’s the money?” he asked, feverish and stern.

I said nothing.

“Angela, I need you to tell me where you put the money.”

“You told me not to tell you.”

“I know what I told you. Now, I am telling you something else. Where is the money?” he asked through his smile, teeth clenched, a hand loosely gripping my neck. I felt eyes on us, my chest burning, my breaths shallow.

“Under the mattress.”

He lifted himself out of his chair and made his way toward the elevators.

“E,” I called out, trotting to reach him. “Please don’t do this. You said you wouldn’t do this.”

“You’re being such a little cunt, you know that?”

Heads turned, voices hushed. Paralyzed by the word, I stood there until he was out of sight and the people dispersed. Then I walked back to the table, berating myself for not leaving him to rot.

****

When he returned, it didn’t take long for him to lose the rest. It was the gambler’s fallacy in full effect: that is to say, if something happens more than normal during a given period of time, the player believes it will happen less in the future. By this logic, a string of losses for E foreshadowed an imminent win, and he would do whatever it took to realize it. The notion that someone could do something so obviously irrational at the time seemed, to me, impossible.

How strange it was to persist in being a part of something I knew I didn’t want to be a part of. How strange to have denied truth when it laid itself bare in front of me. And yet, I allowed myself to steer toward disaster, as if I wanted to see just how bad the bad thing was.

“I’m going to need you to spot me some money,” he said, his gestures communicating my culpability.

“I can’t do that.”

“You can. I need it. I’ve lost everything. I know I could win it all back, but not without you spotting me.”

I stared at the open textbook in my lap, words blurring, diagrams distorting into mandalas, the entirety of existence in my lap at that moment. I hoped if I stared long enough the problem would resolve itself, the demand would disappear, the noises would cease, the staring eyes would melt, and E would rewind back to before he met me, the tape of the past year and a half of our lives unspooling at our feet, writhing like maggots, swept away forever into the Mojave by all those scurrying shoes. And then the Yellow Brick Road would appear and I would be small again and slide off the chair, the Imperial Palace collapsing around me as I scrambled toward Emerald City, Mom and Dad behind me, urging me to go forth, loving me all the while.

But the Yellow Brick Road had been demolished years before. Emerald City, too. And Mom and Dad, though still there, were hundreds of miles away, so much older now, no longer my omnipresent protectors.

“Angela. Let’s go,” he said, that big coarse hand of his clasped around my shoulder, freedom suffocating me.

We hurried to the ATM, E’s arm linked in my own, each step stripping my mind from my body a little more as I wondered how this happened, my head down, recognizing neither my feet nor his. Not ours. Not possible to be responsible for becoming this person, I thought, disassociating entirely, calculating how much had been taken from me and how much I had given away, as though arithmetic could solve it. But it couldn’t. And I was furious because I did not know the difference anymore.

We took out the maximum allowed by Wells Fargo: 500 dollars. The machine coughed out the bills like cards being dealt. E grabbed the wad and marshaled us back to the table, but mid-stride I stopped him. “Why can’t you just walk away? Haven’t you lost enough?” I snapped. He laughed that ruined laugh and kept going and I went with him, propelled by dogged willpower to go the full dizzying distance.

When we returned to the table, I sat behind him and said nothing more, but considered this: perhaps those questions were not for my Man Who Fell From Grace. Perhaps they were for me.

****

Throughout our two years together, E must have moved house nearly a dozen times. We spent our weekends pretending to be people we weren’t, with money we didn’t have. In the beginning it felt glamorous to assume the posture of adulthood, but toward the end it felt dark and sad. All that secrecy and duplicity made me forget who I was, and it wasn’t easy to dispose of the girl I fashioned myself into during my time with E. She was all I had, and if I lost her, what would be left?

He did a virtuosic job of impersonating the man he thought he was – the man I was certain, with time, he would become. So I wove through the Valley for him until a leasing agent would fall for the charade, just like I had. Then we’d throw the air mattress and dirty clothes into the trunk and move house. My life became a series of sunless snares nestled between highways and gas stations, face smashed against stale-smelling inflatable beds. And though it was an itinerant life, it was exhilarating. It felt, at least, alive.

My life with Mom and Dad was the antithesis of this. For over a decade, we lived in a 1,000 square foot apartment in a 400-unit complex, a time-capsule of our life when we first moved in, our charcoal-grey Nintendo and Disney VHS tapes stubbornly standing their ground. The space did not lend itself to secrecy, let alone privacy. I had my own room, but Mom never understood that though I still physically inhabited the nest, I had emotionally left it by the time I met E. And Dad, though better at granting me the space I needed to grow, couldn’t help imposing rules and restrictions out of habit – and, during my time with E, out of mounting fear. When he found out about Vegas, he saw red with the kind of sorrowful rage that only a parent can feel.

I was sat in the jacuzzi reading when he approached me. He must have just come home from work because he was still in his suit. “Did you go to Las Vegas?”

I stared blankly, my body tightening, my mind rewinding the final 24 hours at the Imperial Palace a few weeks prior. The fighting and the fucking. The hysteria and the silence. The crushing wordlessness of the ride home, in darkness just like it had begun, Las Vegas receding behind us, its lights swallowed by the Mojave, the mirage extinguished, and all its attendant promises flattened into dust.

“Did you give all your money to this monster?” he asked holding the white Wells Fargo envelope in his hand like a subpoena. “Your mother remembers where he lives. We’re going there now.”

“No. You can’t do that,” I yelled, my pleas echoing in the courtyard, bouncing off every balcony, relief in realizing I no longer had to hold this secret swiftly supplanted by rage.

“I can and I will,” he said, slamming the gate behind him as I scampered after, towel trailing behind me, wet feet plonking against the cement.

“Please, please don’t do this,” I cajoled, tugging on his sleeve. He looked back at me.

“This monster,” he spat, tearing his sleeve away from my grasp, “took everything from you. And you let him. You fucking let him. And he’s not getting away with it.”

****

I spent hours performing the ritualized laments of adolescence with no audience. Beating my chest, clawing at the walls, bellowing, fidgeting to disperse the pain. Then suddenly, the tables had turned, and I was the one calling Mom and Dad over and over. But my calls were unanswered.

When they returned, I stood shamefaced as Dad sat in his reclining chair and rattled off the details of my defeat, each one like a blow to the head. One: the car approaching the apartment complex. Two: spotting E as though he were a suspect in a line-up. Three: rapping on the glass door of the building’s gym. Four: E’s swagger onto the sidewalk where Dad issued his decree. The verdict was reached: Guilty. On all counts, guilty.

It was as though my father had become the omniscient narrator of my life, ferrying me to places I had no interest in going, taking from me what I had no interest in losing. “I asked him how he could live with himself,” said Dad, tie still on, legs crossed, the contortion of his body suggesting what I figured was conceit. “I asked him how he could live with himself and he just laughed. He laughed, Angela. He’s a monster. Do you understand? I see his type in court every day.”

“That’s what this is about,” I snapped. “This is about you needing to be the man. This is about your Y chromosome bullshit.”

“Oh honey. You’ve got it so wrong.”

“I could have handled it. You fucking mortified me,” I barked, face hot with shame, entirely oblivious to the bravery and devotion just demonstrated by the man in front of me, the meekness of his aging frame counterbalanced by his formidable love.

“Angela. This is the end of the line. You hear me?”

“What the hell does that mean?”

“That means, I don’t get care if you’re technically an adult. You live under my roof and I’m telling you you can’t see him anymore.”

“Well then I won’t live under your roof.”

“Fine. Ruin your life.”

“It’s that fucking easy for you to roll over.”

“I am tired. I am so tired,” he murmured, his hand pressed against his forehead as though shielding himself.

“Baby, don’t be mad at him. He loves you. He did this because he love you,” Mom said to me.

“He doesn’t fucking love me. What kind of a man strikes his daughter with a shoe? What kind of a man are you?”

He bolted upright, fists clenched.

“Out.”

I stood there wishing I hadn’t said that, but my pride wouldn’t allow me to apologize.

“OUT,” he roared, his whole body shaking, Mom weeping behind me.

I tried to make it work for a week, maybe two, until it became untenable. Clothes and books were heaped in the backseat of my car and takeaway boxes dominated the passenger’s seat, leaving only a sliver of space for me. Because E didn’t offer to take me in, the car was designated as transportable storage unit.

“You could spend a night or two here, but you can’t stay indefinitely,” said E when I showed up, overnight bag in hand.

He laughed, Angela. He’s a monster. Do you understand?

I spent the night despite myself, porn playing on the flatscreen, E’s hands slithering up and down my body, his stale, resin-smelling breath on my neck, in my mouth, until he had his fix and passed out. I watched him, his face slack with sleep, and examined him closely, as though the reason I sacrificed so much would finally unveil itself to me. But it didn’t.

I was searching in all the wrong places.

****

Nothing changed in my absence. There sat the same chipped reclining chair. The same Nintendo console and Disney VHS tapes. The same blemished, beige carpeting. The same Mom and the same Dad. But I felt it wasn’t home I was returning to. It was retribution. Sentencing.

Dad told me how I would make amends for my transgressions as Mom sat beside him with imploring, charcoaled eyes. He would pay off my debt and I would pay off my textbooks. He would cut me off completely if he ever found out I was seeing “that man”. And he asked me if I heard him, but I didn’t. I couldn’t hear anything over the din of my longing.

“We’re entering into a verbal agreement,” he said, eyes narrowing. “If you choose to breach it, I will exercise my full right as the wronged party. Do you accept the terms?”

I stared at him, my father, my captor, and lied. “Yes.”

When Dad escorted me to our local Wells Fargo branch he strode ahead, decorously, as though in court, his shabbily dressed, destitute client trailing behind him. “I’d like to pay off my daughter’s credit card” he said, glancing sidelong at me. His intonation, deferential and professional, was not dissimilar from the one he employed when asking the judge permission to approach the bench.

I handed over the necessary identification and stared out the window, the manager’s fingers striking the plastic keyboard. Suddenly I felt like laughing, hysterical from the absurdity of it all. “How would you like to pay for that?” “Check,” Dad said as I stared at the moving cars, a reminder that life was out there and I would soon be part of it, free – though whether or not it was freedom I was after remained unclear. What I really wanted was more elusive than that. What I wanted was vindication.

The verbal agreement meant little to me, and though E and I saw each other less frequently after the Wells Fargo incident, we did not cease communication. I still believed he would come around; that he would reveal himself to me, benevolent and luminous, if I were patient enough. Good enough. And the only person who could lead me to believe otherwise was myself.

If I couldn’t prove that E would love me, if I couldn’t win – and I knew I couldn’t – I needed to lose everything. And I needed to be the cause of it.

****

It happened when the sun was out, when the kids were coming home from school. I remember wearing hiking gear; E and I planned to spend the day at Malibu Creek State Park, our 8,000 acre secret in the Santa Monica Mountains, all rolling tallgrass plains, oak savannas and chaparral-covered slopes.

After years flitting from one hovel to the next, E had graduated to a gated community in Woodland Hills near a multiplex, an Asian-themed restaurant chain, and a slew of sports bars. It was one of many portraits of an American Dream of which I was starting to comprehend the contours. Maybe I want this life, I thought, exiting the freeway, assuring myself that this time would be different, knowing full well it wouldn’t.

I remember him looking happy, basketball shorts on, water bottle in hand, jauntily descending the steps. I remember him opening the car door and hugging me, that long, brawny wingspan engulfing me, his face obscuring everything, just like at the onset. Just like when I thought I loved him.

What caused us to go from civil to acrimonious that day is unclear. Words were exchanged, full of old resentments, and I pulled the car over. My body wanted him out. Before we even reached the gate my mind was screaming, begging me to start over, to leave him to rot, laughing on the pyre of money and women and friends to which he set so many matches, all fodder for his flame. He was finally luminous to me – not in his benevolence but in his self-immolation.

I hated him then. Almost as much as I hated myself.

“Out,” I said, my voice sounding just like Dad’s.

E sat there, refusing to move.

“OUT,” I yelled. And E laughed.

“Are you kidding?”

“I’m not kidding. Get the fuck out of my car.”

He stared at me, as though not immediately paying heed to my demand gave him some kind of power, Then, he leapt out and swooped around to my side.

“Roll down the window,” he said. And I did. Despite myself, I did, part of me still shouting he is benevolent, he will love you, he will choose you. My hope, still so wild and stubborn.

With great precision, he spat on my face.

I wonder now if what happened next had anything to do with E. I wonder, when I was sobbing and screaming and blindly spitting and beating his chest and scratching his arms and clipping his face until I saw blood, if I was trying to push him far enough to punish me. To strike me until we were both bloodied, lifeless, redemption-less things. Maybe then I would learn. Maybe then the whole mess would come to an irrevocable end, and I wouldn’t have to worry about keeping secrets. I wouldn’t have to worry about anything anymore. It would be totally, immutably over. My agency, stripped. Life, quashed.

He took all of it though. He let me hack away at him, with all the fury of two years, as people rushed out to see what all the commotion was about. One woman peeled me from E and guided me to the corner of the parking lot where I stood, hollowed and mortified.

“I’m fine,” I told her.

“What did he do to you? What happened?”

“Nothing. We’re fine. I’m so sorry for the disturbance.”

My last memory of E is him weeping in the passenger’s seat, curled up and shaking violently. He was not crying for me, though: he was scared the police would come and take him away.

“If they see the scratches on me, you’ll be fucked too,” he said.

“Give me my keys and get the fuck out of my car.”

“Angela, did you hear me? Look at yourself. You have no marks on you. If you call the cops, they’re gonna take you in and they’re gonna question you. Is that honestly what you want?”

“That’s bullshit. I’ll tell them I was defending myself.”

“You don’t have a leg to stand on. Trust me,” he said, his eyes almost kind for a moment. Then: “There’s a warrant out for my arrest, ok? Please don’t do this,” he wailed, grasping my arm, his head shaking on my thighs. “Please, please, please.”

And for the first time, I not only saw it: I felt it. I knew it. The money was gone. Forever gone. The man, a husk. The faith, doused. And the desire to be loved was finally superseded by the desire to survive.

E would never reveal himself to me, benevolent and luminous. I never saw him again.

When I asked my best friend what it was like to be around me during that time, she told me she knew I knew I wasn’t living my best life. It was both reassuring and upsetting to know that that was the impression I gave. That I knew I was sabotaging myself and kept right at it regardless of the toll it took.

She told me that I bailed on Thanksgiving one year. That they were all waiting for me and I never answered my phone. Never showed up. And this was the worst bit: She remembered me feeling remorseful, because I knew I hurt someone other than myself. But I remembered none of this, and I tried to understand how. I had always understood why people resort to secrecy in order to protect those around them, even to save face. But I had never considered the secrets we keep from ourselves.

And here’s mine: It wasn’t California that did it to me. Or the mythos of the American West. Or the sun, or Dad, or all that bountiful land.

It was me.

****

Art direction by Whitney Conti, and illustrations by Edda Karólína. Conti is an artist and creator based in London. Her website is here.

Karólína is an Icelandic artist, currently doing an apprenticeship in sign writing in Scotland. Recently graduated from graphic design, Edda’s work borders between fine arts and graphic design, often blending together techniques like illustration, printing, digital design and painting.

Angela Brussel is a writer based in Brooklyn, New York whose non-fiction and fiction have appeared in The Awl, Nylon Magazine, Electric Literature, The Wrong Quarterly, and Brooklyn Magazine. Her current interests range from nihilism and the neuroscience of addiction to the psychology behind conspiracy theories and persecution. Her website is here.