I don’t recall ever meeting a monied Jew when I was growing up in Manchester. We certainly didn’t know any. A few comfortable ones, maybe – but the rest of us worked hard to make ends meet, some improving as the country itself became more prosperous, others just getting by. The two big events in my family’s financial history were my father’s having to pawn my mother’s engagement ring and his accidentally leaving £50 in cash in a public phone booth. He’d sold our old car to a friend and was calling my mother to give her the news that we were solvent for another couple of months. He didn’t notice he’d lost the cash until he got home. He never retrieved it but was able to redeem the ring when he became a taxi driver. So the idea that Jews were money-sympathetic as though by necromancy – money-adept, or just money-aware – struck us as laughable.

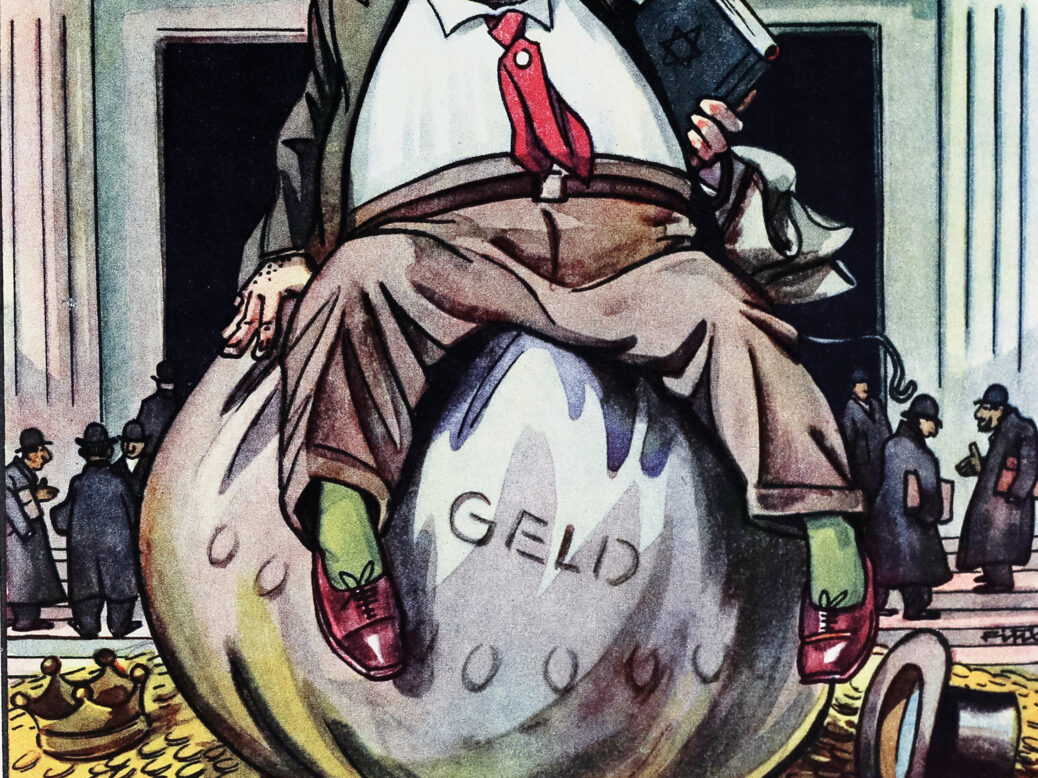

The first object to catch your eye when you begin to walk around the excellent exhibition at the Jewish Museum London, Jews, Money, Myth, is a dictionary from the 1930s open at the entry for Jew: “Jew, v, colloq. 1845. trans. To cheat or overreach.”