When Hannah Arendt was herded into Gurs, a detention camp in south-west France in May 1940, she did one of the most sensible things you can do when you are trapped in a real-life nightmare: she read – Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, Clausewitz’s On War and, compulsively, the detective stories of Georges Simenon. Today people are reading Arendt to understand our own grimly bewildering predicament.

Shortly after Trump’s inauguration, Arendt’s 1951 masterpiece The Origins of Totalitarianism entered the US bestseller lists. Tweet-size nuggets of her warnings about post-truth political life have swirled through social media ever since. Arendt, the one time “illegal emigrant” (her words), historian of totalitarianism, analyst of the banality of administrative evil and advocate for new political beginnings, is currently the go-to political thinker for the second age of fascist brutality.

It is not just the opponents of far-right nationalism who are rediscovering her work. Germany’s far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) has attempted to garnish its claims to serious research with a half-quotation from Arendt. The AfD’s intellectual mission, in case you hadn’t guessed, is to create “clarity and transparency” in public discourse. They warn us sagely that power, according to Arendt, “becomes dangerous exactly where the public ends”. Power, Arendt also said, becomes dangerous when the capitalist elite align with the mob, when racism is allowed to take over the institutions of state, and when the aching loneliness of living in a fact-free atomised society sends people running towards whatever tawdry myth will keep them company.

It is true that Arendt loved the public space of politics for the robust clarity it gave to the business of living together. It is also true that she argued for a political republic based on common interest. These are both reasons why we should be reading her today. But her commitment to plurality is not an invitation to nationalism. Arendt wanted politics dragged into the light so that we might see each other for what we are. But that didn’t mean we had to accept what was evidently ruinous to politics itself, merely that we had to acknowledge that what we find most repellent actually exists – and then resist it.

And if there is one thing we have learned over the past two years it is that our political reality is not what we thought it was and still less what we would like it to be. Because the times she lived in were also dark, violent and unpredictable, and because she was smart, diligent and hardworking, Arendt was good at thinking quickly and accurately about the politically and morally unprecedented. She distrusted easy analogies, thought historical precedents were a poor way of grasping the unexpected, and practised instead what she called “thinking without a bannister”. It is less as a Cassandra from an earlier chapter of history that she has lessons for us today than as a political thinker of the uncomfortable and difficult.

****

Thinking is key to Arendt’s life story. Born in 1906 in Königsberg (Kant’s home town), the much-loved and precociously smart only child of left-wing parents had plenty to think about from early on. First, there was her father, his syphilis, and final mad decline into death when she was just seven years old, turning the world she thought she knew strange and uncertain. Then there was the anti-Semitism that snuck up on her with playground catcalls and the swift realisation that the spite of children was shared by many of the adults around her. Her mother taught her that when you are attacked as a Jew you must defend yourself as a Jew.

Thinking was Arendt’s first defence against a perplexing world. But thinking was always going to be more than something you did with your mind; it was to be her way of being in the world. This was the lesson she took from her teacher and one-time lover, Martin Heidegger. Arendt was just 18 when, in 1924, she first encountered Heidegger at Marburg University. It is unlikely that (as some suggest) it was his lederhosen or the way he slung his skis over his shoulders that led her to his bed, but she was passionately persuaded by his argument that it is through words that we think, exist – and love. “We met”, she later said, “through the German language.”

Words mattered intensely to Arendt both because we think with them and because they make living together possible. She wrote in three languages and read and thought in at least six. It was not, she later said of German, the language that went mad. But by her twenties, people had started to go mad, and even the sane and thoughtful she counted as her friends retreated from increasingly obscene political reality into silent opposition. As a Jew, Arendt did not have the luxury of “inner emigration”, and for the rest of her life she thought – and fought – her way back into a world that, at one point, challenged her right to exist at all.

****

Thinking saved Arendt’s life on more than one occasion. Her early studies in European political history had left her with few illusions about the ability of the Rights of Man to protect anyone from the violence that bubbles up when political institutions collapse. When the dark times came she acted accordingly.

Arrested by the Gestapo in 1933 for researching anti-Semitic propaganda, she quickly spotted that she’d been netted by a reluctant rookie, and simply talked herself out of jail. When in 1940 the call came to her refugee community in Paris for all childless “enemy-alien” women to assemble at the Vélodrome d’Hiver for deportation, she was one of the few with the courage to fear the worst. She fled Gurs internment camp amid the chaos of the German invasion – those who stayed were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Putting Simenon’s lessons about subterfuge to good use in Marseille, she tricked the authorities into thinking her husband had already been arrested.

Arendt’s mature political understanding was formed in those places that the AfD and their friends find troublesome: in migrant communities, along the refugee rat runs, among the rightless, the wretched, and the defiant. She was a self-proclaimed pariah, a term she borrowed from the radical Jewish thinker Bernard Lazare, who had learnt from France’s Dreyfus Affair that assimilation was no protection against racism. The refugee pariahs, she claimed, were the “vanguard” of their peoples, and Arendt was proud to be among them.

As today’s refugee activists will understand all too well, for Arendt’s generation it was a battle to get people to realise that what was happening was not merely bad luck for others, or a humanitarian problem to be managed, but world-changing. “Apparently, nobody wants to know that contemporary history has created a new kind of human beings – the kind that are put in concentration camps by their foes and in internment camps by their friends,” she wrote in a bitterly beautiful essay, “We Refugees”, in 1943. By then, Arendt had escaped Europe for New York, and was beginning to claim her place in what would soon become one of the most significant intellectual groupings of the 20th century, including Hans Jonas, Irving Howe, Robert Lowell, and Randall Jarrell, Mary McCarthy and WH Auden.

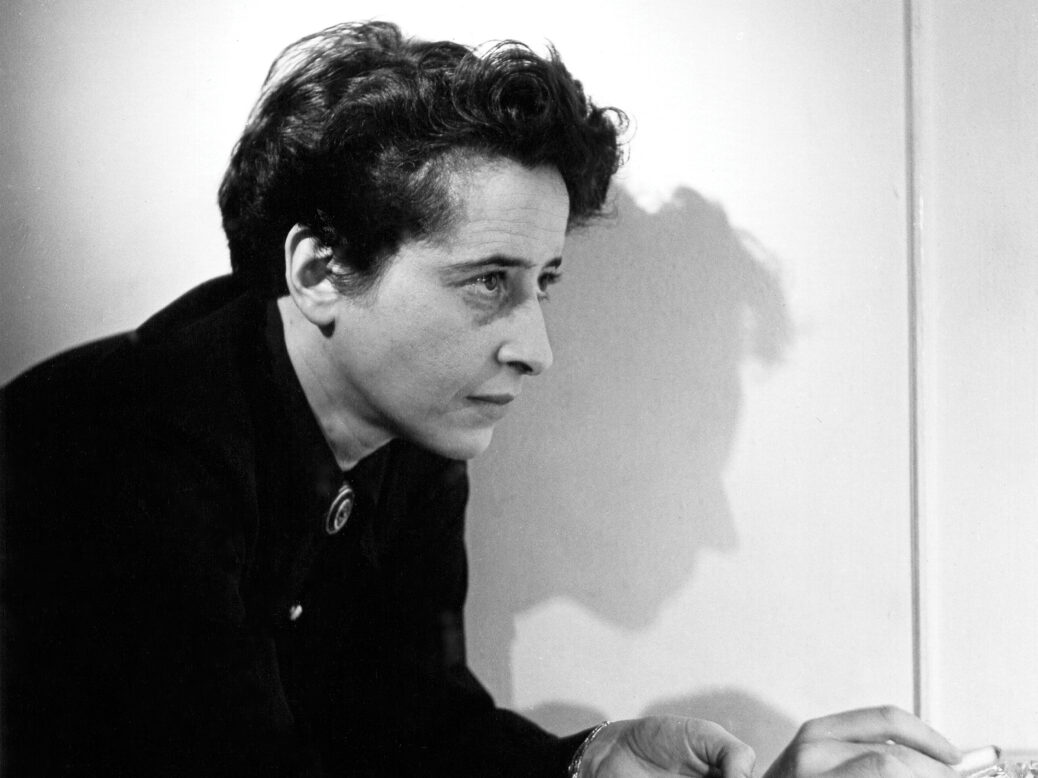

A famous photograph taken in 1944 by another Jewish refugee, Fred Stein, captures Arendt’s intensity – and beauty – in these years: she leans forward in profile, staring steadily into the future, a cigarette held between her long fingers, its ash about to fall. Arendt loved smoking as she loved her friends, habitually and deeply.

Impatient with intellectual fame and suspicious of public posturing, Arendt kept herself and her companions close in the second half of her life. She died in 1975, among friends after a good dinner. This companionability was as defiant and political as it was personal. Her “new kind of human beings” were not only victims of Nazi persecution. Jewish refugees, like those from the global south today, were deemed superfluous by everyone, the “scum of the earth”, as Arthur Koestler described himself and the millions of others who trod the same refugee routes as Arendt. Even before the full horror of the death camps became clear, Arendt had spotted that the world “found nothing sacred in the abstract nakedness of being human”. It still doesn’t.

This wasn’t just because people had become unempathetic and nasty due to mass propaganda, but was also a consequence of the organisation of the world into nation states. When a person is driven away from one country, she argued, he is expelled from all countries, “which means he is actually expelled from humanity”.

Human rights were non-portable. This was particularly bad news for those who found themselves in the way of the establishment of ethnically homogeneous nationalist states, as happened to the Jews and other minorities when Europe was divided into new nation states after the First World War. It happened again to the Palestinians in 1948. On Israel, Arendt was troubled but again clear-sighted. Like “virtually all other events of the 20th century,” she wrote, “the solution of the Jewish question merely produced a new category of refugees, the Arabs, thereby increasing the number of stateless and rightless by another 700,000 to 800,000 people.”

Only a political organisation without nationalism, or one that would at least put nationalism in its place, could guarantee the “right” of everybody to “have rights” – to speak and be recognised as part of a community. Her own statelessness taught Arendt that we make our own humanity, together, through friendship, talk, action and, above all, politics. “We humanise what is going on in the world and in ourselves only by speaking of it, and in the course of speaking of it we learn to be human,” she later said.

****

Hannah Arendt covered the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann for the New Yorker

She also knew that learning to be human in inhuman times was hard and occasionally impossible work. People are fond of pointing out Arendt’s mistakes in this matter, and, as is the case with many women thinkers, there is a conspicuous amount of complaining about what she got wrong about men. It is true that the two men in question were both Nazis: administrative mass-murderer-in-chief, Adolf Eichmann, whose trial in Jerusalem she reported for the New Yorker, unleashing a scandal with her cool-headed analysis of the banality of modern evil; and Heidegger, who joined the Nazi Party in 1933 and became, under its auspices, the Führer-rector of Freiburg University. Heidegger was a pretty pathetic and opportunistic Nazi, but there is no doubt he was an anti-Semite. Arendt was, understandably, revolted; less understandably, she later forgave him.

In truth, the Heidegger who Arendt eventually let back in her life, like many older men nostalgic for what they once were, was a bit of a numpty, a narcissist who called her his “wood” and mythologised their past. The slightly creepy fascination with their affair has underplayed the significance of her relationship with her second husband, the super-smart and ever-fanciable Heinrich Blücher. True, Blücher was also fanciable to other women, including her friends, but here too Arendt was a realist. Blücher picked up her dropped commas and always looked at her with a sparkle in his eye. If she forgave Heidegger in the end, it was because he needed her more than she did him.

Heidegger, the cunning fox who turned out not to be so cunning after all, had set a trap for himself by his own self-absorbed thinking. Eichmann, on the other hand, was distinguished by his total lack of critical self-reflection. Captured by the Mossad in Argentina, the Nazi SS Obersturmbannführer who ran the deportation of Europe’s Jews to the death camps was put on trial in 1961. Arendt was determined to go and look at this “living nightmare” face-to-face. What she found sitting in the glass booth in the courtroom was a man with a cold incapable of blathering anything but clichés. Many have accused her of getting Eichmann entirely wrong. Evidence shows that he knew exactly what he was doing: he was unequivocally a bad man. But Arendt never claimed Eichmann was a guileless patsy; instead, she said, with characteristic irony, he was “merely” and catastrophically thoughtless. That “merely” refers to the insouciant thoughtlessness, not to the crime.

Thinking, Arendt argued, is the two-in-one conversation we have in our heads all the time, and nobody wants to be in dialogue with a murderer – except for men such as Eichmann. This is what Arendt meant by the banality of evil. It is the thoughtlessness that permits you not to consider the moral consequences of what you are doing when you implement a new transport system for the manufacture of people into corpses. Eichmann was a new type of criminal for the 20th century – not simply a genocidal murderer but an enemy of humanity because he could not, and would not, think from the perspective of anyone other than himself.

It was not satanic cunning, but vain thoughtlessness that condemned so many to misery, suffering, and death. That was what Arendt found truly unprecedented about her time. An atomised, mass media-driven society combined with an ever more baroque bureaucratisation of our lives had made this possible. It continues to do so.

****

The AfD is not wrong to say that power becomes dangerous at the point where there seems to be no public accountability any more. But it is precisely at such moments, Arendt teaches, that we most need to think politically, to resist populism: “When everybody is swept away unthinkingly by what everybody else does and believes in, those who think are drawn out of hiding because… [thinking] becomes a kind of action.”

Arendt wrote these words in 1971. The Pentagon Papers scandal had broken earlier that year. One year later came Watergate, and the essay that many are turning to now, “Lying in Politics”. There has always been lying in politics, she wrote; what was new and dangerous to the American republic was not lying, but a situation in which lies had become indistinguishable from the truth. Without grounding, facts run as free as the chuntering of the latest narcissist, and what seemed impossible – children in camps, indefinite detention, thoughtlessly crass nationalism – becomes possible again.

How to resist? How to put thinking into action? Another of Arendt’s essays was on civil disobedience. She began it with yet another currently resonant question: “Is the law dead?” Arendt entertained no fantasies about the law’s higher calling, or its moral authority to do good. The law mattered because it was the existential fiction that glued the story of American constitutional politics together. That was why civil disobedience to defend the law had to be a collective political act: it is the political community and not individual conscience that is at stake. Arendt supported the anti-Vietnam and student movements of the early 1970s because she believed that their actions were making something new – she always had time for those she called the “new people” – out of an essentially good political tradition.

But she also understood that the law, like the republic itself, was founded on violence, racism and conquest. The more troubling question at the heart of the essay is also one for today: why would you defend a law that was founded on your exclusion? More broadly, what happens when the so-called superfluous people of the world – the pariahs, refugees, migrants, black and brown people, the rightless – turn their thinking into political action?

Arendt could not answer that question in late-20th-century America, because she could not think her way into the transformative politics of black activism. In the end, it wasn’t the Nazi men she got wrong, but a young black woman named Elizabeth Eckford. Eckford was the girl depicted enacting her right to a desegregated education amid screaming white people in the now iconic 1957 photograph from Little

Rock, Arkansas.

Arendt argued that Eckford should not be carrying such a political burden at her age and that education was a social and largely private matter. The writer Ralph Ellison replied that all black children in the south carried a political burden from the day they were born whether they or their parents liked it or not. Arendt shut up. It was one of the few occasions that she failed to judge from the perspective of another.

We cannot guess what she would think of our politics now, and she wouldn’t have respected us for trying. Think for yourself, she would have said. But Arendt left us with an important message: expect and prepare for the worst, but think and act for something better. The impossible is always possible.

Lyndsey Stonebridge is professor of humanities and human rights at the University of Birmingham and author of “Placeless People: Writing, Rights, and Refugees” (Oxford University Press)