Something is always killing music. This Christmas it was the collapse into administration of HMV, the last major high street retailer of CDs and vinyl, following “extremely weak” holiday trading. Hearteningly, people reacted less with indifference towards a fallen corporate giant and more in sadness at the loss of a venue for musical exploration and life-changing epiphanies.

In the 1980s the culprit was home recording. Readers with long memories may recall the cassette-and-crossbones logo of the British Phonographic Industry (BPI)’s Home Taping Is Killing Music campaign – yet this supposed industry assassin failed to destroy the music business, with global recorded music revenues reaching an all-time peak of $26.6bn by 1999. The much-mocked home taping episode only cemented record labels’ reputation as hard-lobbying alarmists for whom the sky was always falling in. Until, at the turn of the decade, it did.

The advent of Napster in 2000 – and peer-to-peer file sharing, by which music could be shared for free by home computers networked on the new mass internet – was the first instance of apocalyptic disruption to an entire industry by new digital technologies. The death of the music industry became a business school staple, an investor’s cautionary tale, consultant catnip. In the 15 years after Napster, sales of recorded music would collapse in value by 40 per cent; venerable companies such as EMI and Virgin Megastore would vanish; and data gestalts such as Facebook, Apple, Google and its subsidiary YouTube would assimilate music as just another proxy in their battle for digital hegemony.

Even so, after many years of being buffeted by the digital hurricane, a humbled music business could finally be settling down to a new and possibly secure normal. Revenues are now rising at their fastest rate since 1995. “Music’s been through massive disruption over the past two decades,” says Annabella Coldrick, chief executive of the Music Managers Forum, “but it does seem like it’s coming through the other side now.”

The way the music industry makes its money today is maddeningly opaque compared to the albums-and-tours model of the past. But somehow, with a mix of gig revenue, licensed “syncs” of songs to adverts and movies, income from those still-controversial streaming services and even old-fashioned physical record sales, it is doing so.

The question is, which part of the music industry are we talking about? Is it record labels, tour promoters, music publishers or the new gatekeepers of streaming distribution? Is it the managers, or the artists who actually make the music? And who is likely to prosper now that music has become just another satrapy of global digital empires?

With its lock on youth culture and its assiduous exploitation of new entertainment formats – the CD boom saw one billion discs sold in 1992, rising to 2.4 billion in 2000 – the recorded music industry seemed unassailable from the 1960s to the 1990s. Yet it was blindsided by digital technology in the 21st century. First, illegal file-sharing and CD burning effectively reduced the price of its premium offering, the album, to zero in 2000-02. Attempts to prevent piracy with uncopyable CDs and “digital rights management” (“just an expensive way to piss off your fans”, according to Coldrick) were farcically unsuccessful.

Then, when Steve Jobs offered a solution with the iTunes Music Store’s legal downloads in 2003, the price proved heavy. Record labels had to accept the “unbundling” of the album (no more paying for nine songs you don’t want in order to get the one you do) and drastically reduced revenue (the industry’s global income fell from $26.6bn in 1999 to $14.97bn in 2014 according to International Federation of the Phonographic Industry figures). Moreover, the record labels had to kiss goodbye to monopolistic control of the physical product and acknowledge Apple as the business’s new digital dictator.

“The crisis came because major labels thought they could tell consumers what to do,” explains Daniel Miller, founder of Mute Records, the independent British label where Depeche Mode, Yazoo and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds made their names. “They didn’t realise they could no longer dictate how people listened. The majors paid heavily for their arrogance towards musicians, the independents and their audience. They lost out enormously and it’s hard to claw that back,” he says. “But now, finally, they are clawing it back.”

The new art of the hustle

It seems that the industry – chastened, consolidated, with fewer major players but many more smaller actors on the scene – may well be turning a corner. BPI figures for recorded music in 2017 showed healthy growth of 10.6 per cent, figures not seen since the Britpop years of Blur, Pulp and Oasis. While the UK industry’s overall revenue (£830m) remains only two-thirds of its 2001 peak, streaming income of £388.8m exceeded that from CDs for the first time. It is growth in a changed world, where music has to hustle alongside social media and video as another component in the attention economy. In this new landscape the power of labels is much reduced.

“It’s a much more even playing field,” says Brian Message, partner in Radiohead’s management company Courtyard and co-manager of Nick Cave and Katie Melua. “Nowadays my role is not trying to get an artist signed to a label, it’s about developing their whole business in a more entrepreneurial way. We’re across things we never used to be, like marketing, promotion, selling music direct to consumers, VIP packages… the whole shooting match.”

When Message began working with Nick Cave in the early 2010s, Australia’s crepuscular chanteur was no longer signed to Mute Records. The new capacities of digital media enabled them to focus on the Bad Seeds’ live show and release Cave’s visceral 2016 album Skeleton Tree – an artistic high point informed by the death of his son – on their own terms through Kobalt, one of the new “label services” companies which offer the facilities of a record label while the artist provides the finance. Cave is now arguably at his creative and commercial peak.

“For artists and managers who’ve been around the block like Nick, we’ve got much more choice,” says Message. “You can sign to a label, do a label services deal, release it yourself, strike a partnership with promoters… It’s a huge change in the landscape.”

This new environment does not just sustain grizzled old stagers. It launches new careers. Artists such as grime star Stormzy can now develop a fan base cottage industry-style, via social media and without the aid of a label, then diversify into merchandise and events while retaining ownership. By the time a record company comes into the picture the artist has the whip hand; Stormzy’s debut was released as a joint venture with Atlantic, not as a conventional signing. His headline slot at Glastonbury this summer is a result of his own work.

Live and precarious

Unsurprisingly, in a world where digital distribution has turned CDs into a legacy format and vinyl into a connoisseur’s objet d’art, the biggest change has been the primacy of live performance. “You used to tour in order to sell records,” says Andy Copping, president of UK touring at Live Nation and promoter of the Download hard rock festival. “That’s turned completely around over the past few years. Live is at the forefront for bands and their survival. Many bands think of themselves as touring outfits that make records rather than the other way round.”

Faced with the cut-throat realities of streaming – where a single play of a song is believed to pay between $0.006 and $0.0084 to be divided between label, artist, producer, publisher and songwriters – the mathematics of live performance look ever-more attractive to established artists. They will take a significantly larger percentage of any ticket price (between 80 per cent and 85 per cent) than the 10 per cent they might receive from selling a copy of that new album that nobody really wants. And while albums retail at £8 to £12, a concert ticket can now be anything from £30 to £100 upwards.

When Martin Fitzgerald of retailers See Tickets started his career at Ticketmaster in 1993, it would shift 3,000 tickets on a good day. Now, when he comes in at 9am See Tickets has already sold that number across music, outdoor cinema, sport, comedy and theatre. “The internet quantified demand as never before,” he explains. “On the old box-office-and-phone model you had no real idea of where the demand really was. Now you can see that you’ve got maybe 20,000 people waiting online for a ticket. It’s like seeing the entirety of the queue for one show outside your window.”

The ability to measure audiences, and to fine-tune ticket prices and release times, plus an arms race of ever-more elaborate stage presentations, have all cranked up demand for live shows still further. Factor in the collapse of revenue from records, and some bands are maybe playing bigger, more expensive shows than they should. Then there is the added pressure of social media commentary. “When Nirvana were planning their final tour, the one that didn’t happen, they booked four Brixtons,” explains Fitzgerald. “But they didn’t have a million people on Twitter all moaning that they couldn’t get tickets.”

Which brings us back to the attention economy. While entertainment options multiply as never before, the only things they’re not making any more of are time and your customers’ attention. Live agent Nick Matthews of the Coda agency recalls walking around this year’s Reading Festival (“always a great experience for a 39-year-old agent, seeing 18 year olds at their first festival”) and noticing a change in behaviour from young fans. “They literally want to see ten or 15 minutes of a band, hear the hits, get their Instagram picture and then head off to see someone else,” he says. “They don’t even have the attention span for a 45 minute set. There is so much more music around, but people care less about it. For a live artist it means you have to become the best in your genre. But overall it’s a five-hundred-horse race and Apple or Spotify don’t care who wins it, they’ll just back the ten that do.”

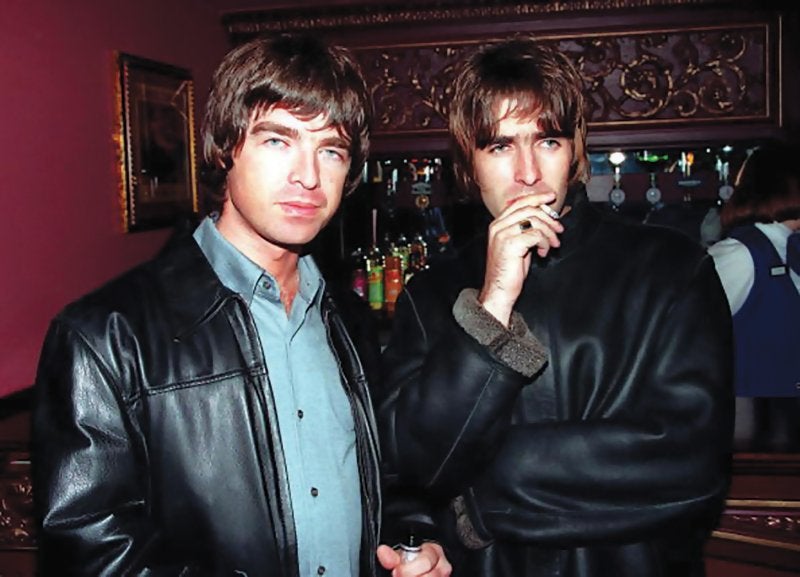

Rich pickings: Noel and Liam Gallagher of Oasis out in London’s West End, 1995

The things that streams are made of

Sooner or later it all comes back to Spotify and Apple Music. There was a time when streaming was a perennial target for music business ire. Radiohead’s Thom Yorke infamously (and oxymoronically) described the new model as “the last desperate fart of a dying corpse” after pulling his solo music from Spotify in 2013. In 2015 Geoff Barrow of trip hop band Portishead attacked Apple, Spotify, YouTube and his label UMC for “selling our music so cheaply” when he received a grand total of £1,700 after tax for 34 million streams. In March last year the rock veteran David Crosby complained to Rolling Stone that the streaming companies had “rigged it so they don’t pay the artist. I’ve lost half of my income because of these clever fellas. I used to make money off my records, but now I don’t make any.”

Yet the volume and vituperation has died down somewhat in recent years, perhaps amid a general acknowledgment that while streaming services don’t pay what physical records used to pay, at least they pay something. And as well as generating money, they’re a real-time source of market intelligence.

“The internet has made it a lot easier to build an audience quickly on your own terms,” says Ellie Giles, who manages Wirral singer-songwriter Bill Ryder-Jones, ex of cosmic Scousers the Coral. “The availability of data means we understand consumers a lot better. You can see what listeners like and where their interests are heading, and book gigs accordingly. You can actually build a business for an artist quickly.” If you can get your artists up to half a million streams a month, she explains, that adds up to £30,000 a year in revenue – a strong foundation from which to build. “From an artist’s point of view, in some ways you’re in the strongest position you’ve ever been in.”

The downside is that aspiring artists must accept the same new conditions as workers in every other industry impacted by digital disruption. You must do more, you must do it for less, and you must do it for yourself.

Doing it for themselves

Elizabeth Bernholz is a Brighton-based musician who makes strange and compelling electronic art-folk under the name Gazelle Twin (imagine Björk convening a spontaneous feminist rave on the set of The Wicker Man). She’s now on her fourth and most accomplished album, Pastoral, and in the past you’d imagine her signed to an avant garde record company such as Daniel Miller’s Mute. Instead, she releases her records on her own label and acts as her own designer, website manager, content creator, marketer and business planner.

“It gets more complex every year,” she says. “The music is maybe 10-20 per cent of what I do.” While Gazelle Twin has legal and management representation and a live agent, “I spend most of my time on admin. I have a team but even so it can be overwhelming. It’s very low paid but the control can be rewarding too.” Though Bernholz has been touring profitably since 2013, it takes a 70-date tour to make a decent income for herself and her family. “If you can compromise and adjust your lifestyle you can make it work. But it’s hard.”

One factor that made Pastoral possible at all was a grant from the Performing Rights Society’s Momentum Music Fund, an industry resource interested not in creating the next Beyoncé but simply in enabling artists to have a viable career. “It’s been a lifeline, the only way to release music independently,” she says. Despite the tough environment she remains optimistic – and there have been flashes of good fortune for Gazelle Twin. On the strength of her Unflesh album she was asked to cover Brian Wilson’s “Love and Mercy” for the TV show The Walking Dead. “It wasn’t a massive payer but it was good for profile,” Bernholz says. “These little things do happen and you’re always thinking ‘There might be another one…’”

Other artists find that the old-fashioned methods work surprisingly well in the modern digital dispensation. In his many years at the interface of dance music and rock, manager David Manders saw the options for developing acts narrow down during the Noughties. “I could get in to see the A&Rs because they’d all wanted to be on the guest lists at our clubs,” he says, “but it got very dispiriting spending your life in offices trying to get money out of them in the later part of the 2000s. They didn’t really have any money at this point.” Then in the early 2010s, the wife of Manders’ business partner booked a small band to play in her clothes shop on Curtain Road in Shoreditch.

“J Willgoose Esq turned up with his old 1950s TV on a keyboard stand and all this electronic equipment, all done up in his bow tie,” says Manders. “He played in the window there and he was very unique – catchy tunes, brilliant ideas. There was something magical about him.” They began managing his band Public Service Broadcasting. “We were never sure it would make it on commercial radio but we thought it would go over really well live, especially at boutique festivals.”

In fact, Public Service Broadcasting proved to be a model cottage industry, with Willgoose producing his brilliantly idiosyncratic records – pulsing indie and Krautrock plus evocative vocal samples from old public information films – at home, at minimal cost. BBC 6 Music came on board (“It connected with that audience because they’re the perfect band for them, they’re intelligent music-lovers, not teenagers with short attention spans”) and Manders was able to finance a debut album through lots of partners rather than one label. “It was lots of little income streams adding up to something we could work with.”

Public Service Broadcasting’s astronautical concept album The Race For Space, their second, went on to sell 120,000 worldwide. It enabled them to work on a more ambitious third, Every Valley, which movingly dramatised the rise and fall of Welsh mining communities. The band is now a fixture at festivals and on 6 Music; in November Public Service Broadcasting played the Albert Hall. “We think about long-term growth for a band like this,” says Manders. “It’s about constant reinvestment, thinking about the future and always connecting with the audience.

“If you’re the superfan, you want the T-shirt and the CD and the gig ticket – that’s all revenue. There used to be just a few artists who did really well but it’s working out now that a lot of smaller bands can do more than just survive. The new world of the music industry is actually really encouraging.”

From break-outs to Brexit

The major labels too are adapting and finding other ways to prosper. In 2015 music giant Universal released the Amy Winehouse documentary Amy, directed by Asif Kapadia of Senna fame, in partnership with Film4. The movie brought Winehouse’s music for Universal/Island together with archive, interview and news footage to create a powerful portrait of the great lost British talent of the 21st century. Amy became the highest-grossing British documentary film in history, taking £3m in its first month. Similar documentary projects with Ed Sheeran and Coldplay followed soon after.

“We’ve broadened from the clichéd record business into a broad-based media and entertainment company,” says Marc Robinson, president of Universal’s partnerships, production and syncs division Globe. “Now we think less in terms of just selling music and more in terms of storytelling.”

Globe works on a spread of partnerships to find value in Universal music in unexpected places. Ad syncs are now viewed as a way to market an artist as well as nice earners: “You’re more interested in the media money that gets the artist seen than the fee for the track.” Globe is using podcast talk shows to broadcast the personalities of acts such as Jessie Ware and Gregory Porter and rethinking the movie soundtrack model by investing directly in films, including Idris Elba’s reggae- and dub-marinaded gangster movie Yardie. “We knew that music culture was integral to that film so we worked with them from script stage,” says Robinson.

“If anything, that crisis in the Noughties made the business realise what it can do with the toolkit it’s got,” he argues. “I’ve worked at Universal for 15 years and we’re at probably the most exciting time I’ve seen in the business.” The classic record company, he says, has had to become more patient, nimble and open-minded. “It’s less sex, drugs and rock’n’roll and more Pilates, herbal tea and a bit of yoga these days,” he admits. “But it feels the most creative it’s ever been during my career.”

And then there is the “B” word.

On the day before the EU referendum in 2016, Daniel Miller gathered the Mute staff together. “I’m not going to tell you how to vote,” he told them. “But whoever votes Leave has to fill in the carnet.” Nervous laughter rippled through the room. The carnet is the music industry’s least favourite thing, a relic of the pre-customs union years when every single wire, plug, guitar and plectrum had to be accounted for when crossing national borders. Now, with Brexit negotiations hopelessly awry, the carnet is back on the agenda as are countless other import- and export-related miseries.

“It’s hard to factor Brexit into your business when you don’t know what it is yet,” Miller admits. Mute’s physical manufacturing is carried out in Europe by the Belgian company PIAS, so ironically movement of goods around Europe should not be a problem. Getting them into the UK is another matter. “We may need to move physical manufacture in the UK but there is a huge backlog in vinyl pressing here, for instance. Demand exceeds supply. No one knows what’s going to happen.”

Ellie Giles is planning 2019 tours for Bill Ryder-Jones and other acts and she’s wondering whether to book anything in Europe after March at all. “For smaller artists, if you’re getting withholding tax, insurance and carnets, is it worth it for a €500 show? This is a global business. I want my artists playing in Europe, America and Australia. But how do I make that possible?”

Annabella Coldrick of the Music Managers’ Forum says the people who are most terrified are the road haulage operators. Who will want to bring pantechnicons full of stage equipment and instruments across the Channel when the M20 is a static car park? Touring firms are already losing out, she says, as global artists who used to begin their European tours in the UK would hire crew and equipment here and rehearse here, but are now beginning to choose German kit and crew instead.

“You’d end up doing a couple of dates in London at the end but really you’re concentrating on the rest of the EU,” she says. “This is affecting festivals right now. People don’t know what to plan for. Every time I speak to the Brexiteer Tories they say, ‘Oh it’ll be fine, there’ll be a visa waiver, carnets aren’t that complicated…’ So many of them are just massively optimistic in the face of all evidence to the contrary.”

Perhaps there’s a final irony here. Having weathered a global storm, this industry found stability in the one thing that digital technology can’t replicate: a communal live experience among other human beings from different backgrounds. Now, in the UK this revival may be overturned, not by technology but by an atavistic rejection of all that is outward-looking. Brexit: the antithesis of rock ‘n’ roll.

This is how it is for the Patient Zero of digital disruption. The music business became the test lab for creative industries that may fear the future but know it can’t be held back. Game-changers seem to come daily. In September, Spotify made it possible for artists to upload their music direct for streaming without the need for a label at all. Apple has bought the team behind Asaii, which claims to be able to predict future hits using artificial intelligence. Meanwhile, it seems likely that the album – which has long been the industry’s creative touchstone and cash cow – could finally be in terminal decline, with American sales down a catastrophic 50 percent last year from 2015. The only constant is change.

And at the bottom of this inverted multi-million dollar pyramid are the artists. In this business, digital technology might have made it easier than ever to play, but it’s never been harder to win.

Andrew Harrison is the producer of the Remainiacs podcast