The ancient Romans called it the cursus honorum: the system by which you moved up the social ranking to get the top positions within the imperial pecking order. In that most imperial and imperious of cities, New York, there is a new variation of the cursus honorum theme. It’s called the A-list. And given how that vertical playpen of ambition is obsessed with winning and all its material trappings, finding your place within the upper reaches of the New York scene remains an ongoing obsession of the hyper-ambitious. The city’s self-importance is vertiginous – so too the way it venerates those with power and clout.

Consider the case of Truman Capote, who squandered his considerable literary talents by playing court jester to a gaggle of Upper East Side society grande dames (his swans, as he called them), who then cast him out into social Siberia when he dared share their whispered confessions in print (did they really expect such an entrenched metropolitan gossip to maintain Jesuitical silence when presented with hot material?). And then there’s Graydon Carter, who mocked the absurd predilections of celebrity while editing the New York Observer, only to embrace it with vehemence and transform himself into a media Cardinal Richelieu – the master power broker – during his years as editor of Vanity Fair. And let us not forget Tina Brown, whose “I’ll Take Manhattan” campaign turned her into the magazine editor as star: her serious talents expended in the celebration of fabulousness.

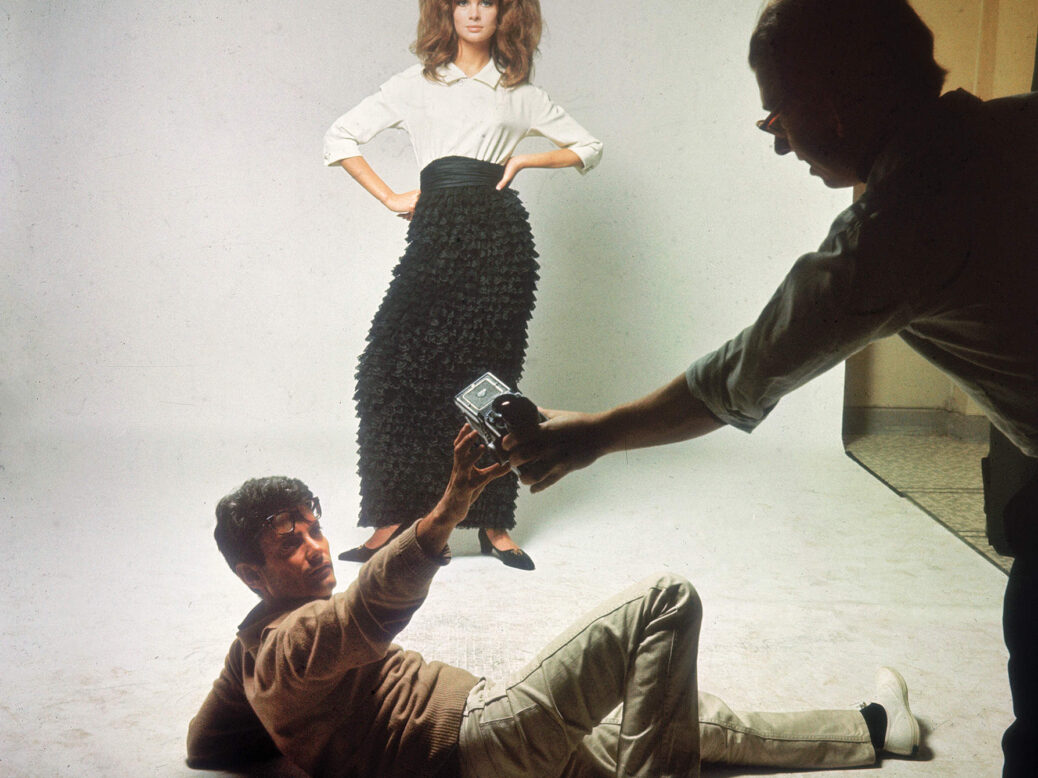

This brings us to Richard Avedon: one of America’s great postwar photographers and someone who (according to this fawning, celebrity-obsessed and rather silly biography) was always dancing on a tightrope between fashion, high art and the A-list. Of course, like any interesting artist, Avedon was a morass of manifold contradictions. A New York Jewish kid whose father’s garment business went belly up, he was raised conscious of the fragility of American success and also of his diminutive stature. Sexually ambivalent, he married twice and fathered a son, but was certainly bisexual (yet someone who rarely cruised any of his models). Falling into photography during a stint with the Merchant Marine, he found his calling behind a viewfinder in the 1940s and quickly became a byword for innovative fashion photography and for carrying himself with immaculate style. Within a few years he was Harper’s Bazaar’s bravura shutterbug, a regular at the Paris collections, and so celebrated as an arbiter of style that Fred Astaire portrayed a photographer based on Avedon in Stanley Donen’s musical confection Funny Face.

From an early stage in his career, he was a fully paid-up member of the New York beau monde. Where Norma Stevens and Steven Aronson’s biography works best is when it details the inner workings of Diana Vreeland’s Harper’s Bazaar and the way that its art director Alexey Brodovitch set new standards for photographic context and layout while battling manic depression and alcoholism. In the extraordinary Irving Penn, Avedon found a competitor whose aesthetic was more severe, who eschewed the limelight and the fast lane, and who was always regarded (perhaps unfairly) as the more high-minded artist – even if, as a portraitist and latterly a chronicler of the American persona, Avedon was a true visual shape-shifter.

Fold into this Avedon’s talent for friendship; his workaholism; his insatiable creative energy; his inability to connect emotionally at a deep level with a romantic partner; his immense private doubts and public brio; his tragic schizophrenic sister; his sexual adventures with his cousin; his brief Paris affair with the director Mike Nichols, and – whew! – you have the basis for a fantastic biographical survey of a charged and singular postwar American life.

Why then is Something Personal such a maddening and stupidly self-indulgent book? Precisely because Stevens – Avedon’s studio director from 1976 until his death in 2004 – sees herself not simply as the keeper of the flame when it comes to his legacy, but also as a sort of bargain basement Boswell, and one who has bought in completely to the “fabulous” swirl of Avedon’s life. Here is one of about a dozen deeply tedious examples of Stevens – whose voice dominates this tale – recounting a soirée that Avedon threw in Jamaica for wife number two:

Evie’s birthday fell on January 16 and Dick, having discerned – the Paleys and Bernsteins aside – Dorothy and Oscar Hammerstein, Jennifer Jones and David Selznick, Kitty Carlisle and Moss Hart, Phyllis and Bennett Cerf, and Fred Astaire’s sister, Adele, realised he had on hand the ready-made ingredients for an A-plus-list surprise party.

Stevens is endlessly obsessed with names, with status, with what Avedon cooked for dinner, and the complexities of the Brooke Shields shoot for Calvin Klein Jeans. Which, it can be argued, was as much of the Avedon persona as his photojournalism work in

Vietnam or on the civil rights marches of the 1960s. But in attempting a kaleidoscopic narrative style – interviews with his close associates intermingled with her own cloying recherches du temps perdu with Avedon – there is the sense of meandering mess to this biography, with none of the thematic or structural rigour needed to contextualise an important life and oeuvre.

The Richard Avedon Foundation has attempted to block the publication of Something Personal, stating that it is “filled with countless inaccuracies”. Punching back, a spokesman for the book’s publisher, Penguin Random House, stated that it “is not a traditional biography” and that “the story which [Stevens] tells recounts the tales that [Avedon] told her in the almost 30 years she worked alongside him”.

Who to believe here – and does it really matter? Stevens might be the ultimate Avedon groupie, but she doesn’t shy away from his darker recesses. What you do come away with is a huge appreciation for his body of work and for his absolute lust for life. Avedon brilliantly captured all the incongruities of his moment in history. It’s a pity his own narrative couldn’t have been better served by a smarter chronicler.

Speaking of darker recesses, one of the more unsettling tales in the Avedon biography comes when, according to one of his former assistants, the great photographer unleashes a tirade of anger on the subject of his great high-school friend, James Baldwin, for the sin of having yet to deliver the text for their collaborative book, Nothing Personal: “Fucking nigger hasn’t done a lick of work! He’s holed up in Finland with his boyfriend and he’s holding up our book.”

Avedon jumped on a plane to Helsinki with his portable Olivetti in hand. He returned a few days later with Baldwin’s manuscript. Norma Stevens states that “the Dick who reportedly uttered that racial slur was not the man I knew”. The year was 1964, a moment when the then US president, Lyndon B Johnson, was pushing through what became a key piece of civil rights legislation while simultaneously using the N-word on a regular conversational basis. This is not to make excuses for Avedon’s dreadful outburst. But it serves as a reminder that back then even a New York artist with all the requisite progressive credentials, collaborating with one of the key African-American writers of his time, could still use the language of the Ku Klux Klan when angered.

The remarkable collaborative effort of Avedon and Baldwin, Nothing Personal, was castigated as quasi-radical chicdom by many a forward-thinking member of the cultural elite when first published. At the same time, conservatives condemned Avedon’s bleak portraits of the American way of life as the sour posings of a New York fashion guy.

Taschen has brought out a stunning new edition of this classic volume. Whether it is his astonishing photos of four American weddings – creating in each shot a novella of class, race, familial allegiances and tensions – or a portrait of the former president Dwight D Eisenhower, looking very much like an elderly man, beaten up by a life in command of armed forces and eight years in the White House during the virulent Cold War Fifties, you see Avedon’s absolute compositional genius; his ability to make you regard the quotidian, or the landscape of the human face, in a wholly new way.

Baldwin’s accompanying text is a furious and brilliant indictment of the way we in the United States endlessly mythologise ourselves. Read today, his essay can now be seen as a prescient commentary on how, by embracing our national lies, we’ve allowed the totalitarian impulse to filter upwards in the body politic: “It has always been much easier (because it has always seemed much safer) to give a name to the evil without than to locate the terror within.” l

Douglas Kennedy’s new novel is “La Symphonie du Hasard” (Éditions Belfond), to be published in English as “The Great Wide Open” in 2019

Avedon: Something Personal

Norma Stevens and Steven ML Aronson

William Heinemann, 720pp, £30

Nothing Personal

Richard Avedon and James Baldwin

Taschen, 120pp, £60

This article appears in the 21 Mar 2018 issue of the New Statesman, Easter special