There is a rare clarity of vision in the photography of Horace Warner. It brings us startlingly close to the Londoners whose images he captured and permits us to look them in the eye.

Warner came to Spitalfields as superintendent of the Sunday school at the Bedford Institute, one of nine Quaker missions operating in the East End of London at the end of the 19th century. Geographically, the “Nippers” in his photographs were creatures of the byways, alleys and yards that laced Spitalfields. Imaginatively, theirs was a discrete society independent of adults, in which they were resourceful and sufficient, doing washing, chopping wood, nursing babies and making money by selling newspapers, hawking flowers or bunching parsley for market. A few swaggered for the camera, but most were preoccupied in their own world and look askance at us, without assuming the playful, clownish faces that adults expect of children today. These Nippers were not trained to fawn by posing for innumerable snaps, and consequently many have a presence and authority beyond our expectation of their years.

Although his subjects were some of the poorest people in London, Warner’s compassionate portraits stand in sharp contrast to the stereotypical images created by other social campaigners of that era, those who commonly portrayed children solely as victims of their economic circumstances and sometimes degraded them further by the very act of photography. Characteristically, Warner granted his subjects the dignity of self-possession and so they present themselves to his lens on their own terms.

In 1913 the Bedford Institute paid two pounds, 15 shillings and sixpence for roughly 20 photographs he had taken of the local children. It used them in its fundraising activities, reproducing them on handbills and collection boxes.

These pictures were selected from a significantly larger body of work that Warner created at the time and gathered into two albums. For more than a century, this collection of images was hardly seen by anyone outside his family, but today they are published as the book Spitalfields Nippers, where they are reunited with the pictures purchased by the Bedford Institute – permitting a full assessment of his achievement for the first time.

Working in the family wallpaper business of Jeffrey & Co, Warner had the income and aesthetic training to explore photography in his spare time and produce images of the highest quality. As a trustee and superintendent of the Bedford Institute, he was brought into close contact over many years with the families that lived nearby in Quaker Street, winning their trust and affection. As a Quaker, he believed in social equality and that the divine lived in everyone. He was disturbed by the suffering he encountered in the East End. In the Spitalfields Nippers, all these things came together as the result of a unique set of circumstances, allowing Warner the opportunity to create exceptional, humane images that gave dignity to his subjects and producing photography that was without parallel in his era.

As early as 1905, there had been an occasion when the pictures were shown to an influential group of people who recognised the power of Warner’s work. Attached inside the cover of his first Spitalfields album is a piece of notepaper from the warden’s lodge at Toynbee Hall, dated 21 June 1905. This institution had been established in 1884 by Samuel and Henrietta Barnett as the first university settlement in the East End, in the hope that educational and social projects undertaken by students from Oxford and Cambridge would encourage a social conscience among future generations of political leaders. (Both Clement Attlee and William Beveridge taught at Toynbee Hall.)

“These photographs were taken by an Associate of Toynbee Hall who has lent them to Mrs Barnett for the use of Lord Crewe,” reads the text of the letter, inscribed in a careful italic hand, with an annotation at the top in red ink: “Returned with thanks, Crewe, 27th July”.

Henrietta Barnett was committed to reforming the brutal regimes of Poor Law schools and in 1896 she set up the State Children’s Association “to obtain individual treatment for children under the Guardianship of the State”. Lord Crewe was one of several powerful aristocrats who chaired the association; it appears Warner’s Spitalfields albums were used as evidence in their political campaign to secure social reforms to support vulnerable children.

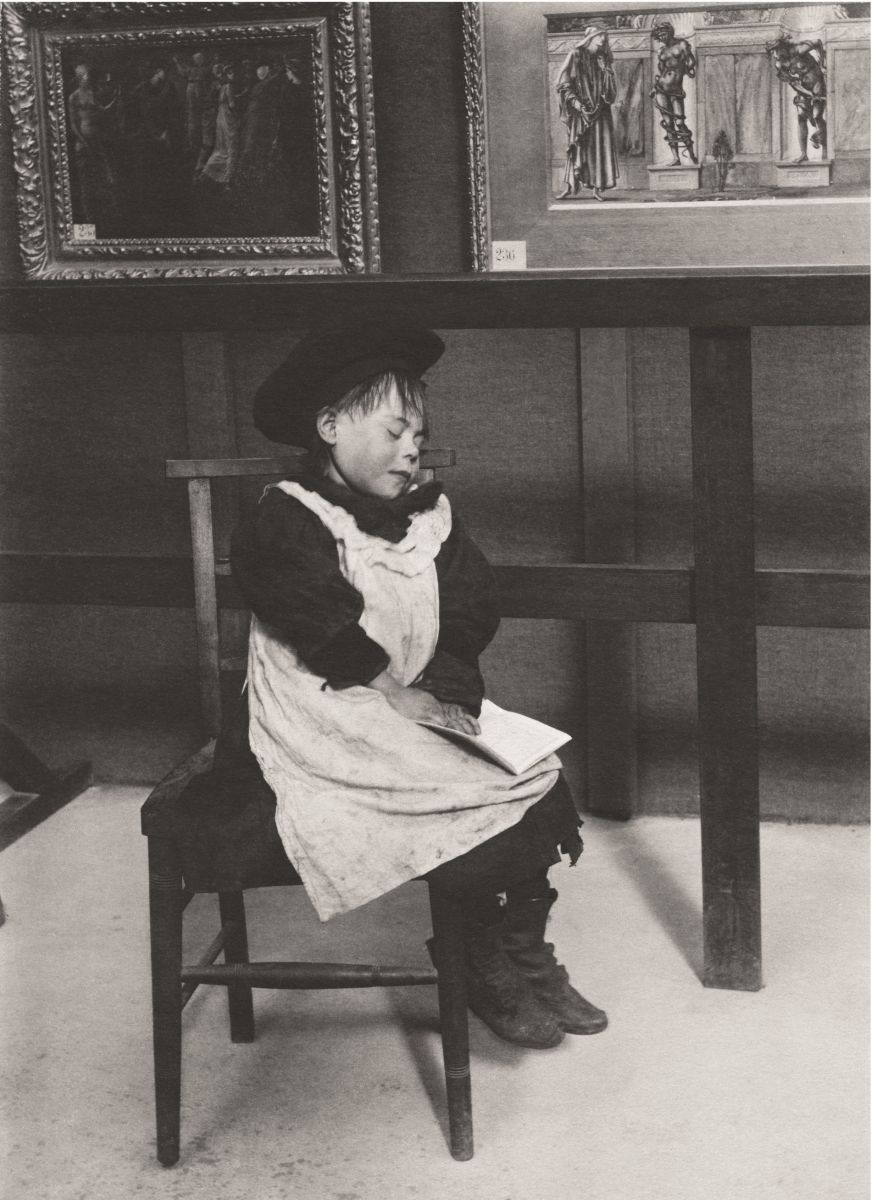

True to his belief in the social value of culture, Samuel Barnett also founded the Whitechapel Gallery, not far from Toynbee Hall. It opened its doors in 1901 with a mixed show of contemporary work, including a selection of pictures by Edward Burne-Jones which Warner took the Nippers to see, leading them on an excursion beyond their familiar territory and capturing their first encounters with fine art. (One Nipper, pictured below right, found the visit the perfect occasion for a nap.)

In Spitalfields at this time, one in five children did not survive to adulthood, but Spitalfields Life researches show that, among the poorest families that Warner photographed, the mortality rate was closer to one-third. Among those who survived childhood, many lived into their eighties and nineties – Rosalie Wakefield of 47 Hamilton Buildings in Great Eastern Street died in 1979 in Waltham Forest, aged 84; Jessica Wakefield of Camden died in Wandsworth in 1985, aged 94. Other stories are shorter: Tommy Nail, born in Kingsland in 1891, and his brothers William and James were all conscripted and fought in the First World War. Both of Tommy’s brothers survived, but he was killed on the battlefield on 9 October 1917.

Much of the world of the Nippers – the alleyways and lanes of the old East End – no longer exists. Samuel Barnett’s hopes of a more equitable society were fulfilled when Clement Attlee, who had been the secretary of Toynbee Hall, became the architect of the welfare state after Labour’s landslide election victory of 1945. Today, with the welfare state in retreat, these pictures of the Spitalfields Nippers are a salutary reminder of the world before social provision came into being. Shamefully, the Borough of Tower Hamlets, which covers the locations where the Nippers were photographed, now has the highest rate of child poverty in London.

Horace Warner’s photographs remind us of how life used to be for many in the East End and elsewhere, and of the human value of the reforms enacted in the 20th century. The struggle to create a modern, compassionate society that can protect its most vulnerable members goes on.

***

“Joey Lyons and Nellie Slark”. Joey was born in 1896 and worked as a boot finisher aged 14. He served in the Second World War, dying at 71 in Suffolk

***

.jpg)

Many Nippers worked to support their families, touting for odd jobs at the nearby child labour market

***

In “Tired of Art”, a young girl rests at an exhibition of paintings by Edward Burne- Jones at the newly opened Whitechapel Gallery, 1901

***

Life in the backstreets: a curious crowd peers down an alleyway at the photographer

***

.jpg)

The “Sisters Ellis” wear matching dresses, probably made by their mother, a worker in the garment trade

***

.jpg)

This image of a boy with a basket is part of a series depicting children working and helping their parents with chores

***

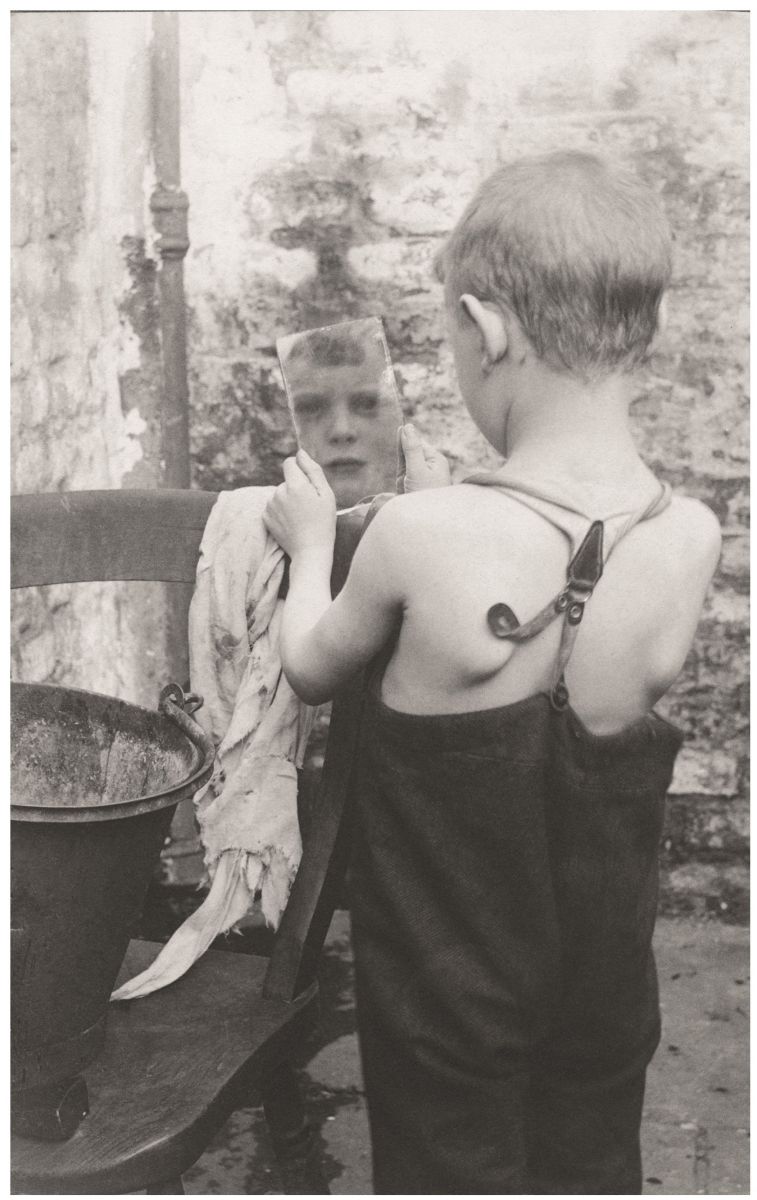

In this image, captioned “Quite Clean ’Nuff”, a boy washes his face in a Spitalfields yard

***

This photo of boys sitting on a wall is captioned simply “Brothers”

***

A girl wears a fine dress from an earlier era, probably obtained at the nearby Houndsditch rag market

***

The Gentle Author writes daily about the life and culture of the East End of London at: spitalfieldslife.com. He will give a lecture on Horace Warner’s work with the Nippers at the National Portrait Gallery, London WC2, on 2 April (7pm)

“Spitalfields Nippers” is out now (Spitalfields Life Books, £20)