The New Lad died a long time ago, but although I certainly had a hand in leading him to the edge of the cliff – he was smart enough to jump before he was pushed – I have to hold up my hand and admit I was partly responsible for his birth.

In 1991 I was the editor of the men’s magazine Arena, which was an offshoot of the 1980s style bible The Face. That year we published a piece called “Here comes the New Lad”, 1,800 words that heralded the emergence of

. . . a rather schizoid, post-feminist fellow with an inbuilt psychic regulator that enables him to imperceptibly alter his consciousness according to the company he keeps. Basically, the New Lad aspires to New Man status when he’s with women, but reverts to Old Lad type when he’s out with the boys. Clever, eh?

The essay anticipated the publication of Nick Hornby’s Fever Pitch, a book that not only elevated football to a cultural position it hadn’t held since the glory days of 1966, but also allowed men to wallow in their obsessional tendencies in a way that had rarely been done before, creating a publishing genre bolstered by Hornby’s next book, High Fidelity, which explored the male fetish for cataloguing music.

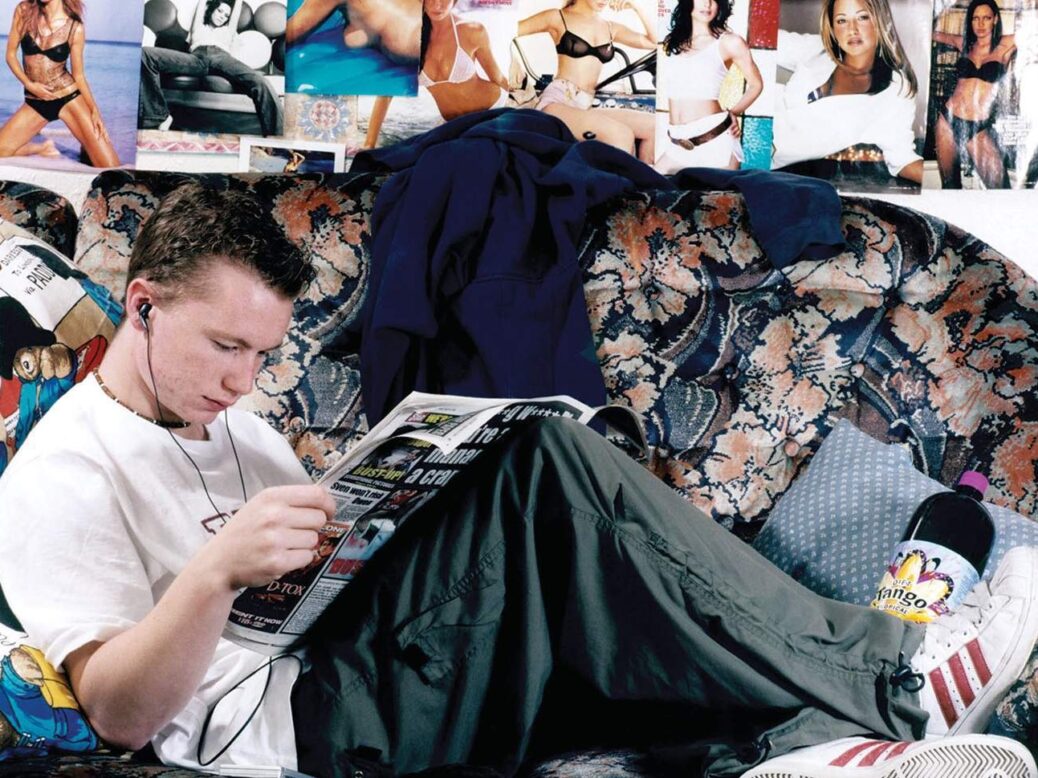

Suddenly, men were encouraged to revert to adolescence, to become myopic in their pursuits, and to claim cultural emancipation in the process. And there appeared to be hundreds of thousands of them. Our piece had identified men’s sympathetic responses to feminism, yet their inability to embrace it wholeheartedly. More importantly, it identified a stereotype that would soon start to define the 1990s – a man who started to have magazines aimed at him: Loaded, FHM, Maxim, Front, etc, ad nauseam, repeat to fade.

To look at the dozens of men’s magazines that launched in the 1990s, seven or eight years after GQ, you could have been forgiven for thinking that the Alpha Male had had some sort of frontal lobotomy. Apparently you couldn’t be a man unless everything you consumed, everything you appreciated, everything you read, watched and listened to came complete with its own inverted commas – big yellow foam inverted commas that proved you didn’t take things too seriously.

Thankfully, that culture has largely disappeared and the dozens of lowbrow men’s magazines have disappeared. As the zeitgeist shifted, and men started to look elsewhere for their entertainment, so these magazines had only one button to press, which they pressed with some repetition and rather a lot of glee: sex. But the circulation woes of these magazines coincided with the mass migration to the digital world, one that was more than happy to offer any kind of sex you wanted.

Personally, I am happy that many of these magazines have gone to the wall, because even though they initially brought a lot of young men into the market, fundamentally they were reductive products that ended up insulting their readers.

When I was commissioned to write this piece, I was asked if, in editing a men’s title, there was a “balancing act” between sophistication and geezerness, the masculine and the metrosexual, the confessional and the confident.

The constituent parts of our magazine are remarkably similar to what they were when we launched in 1988. GQ was born on the back of a massive consumer boom, and reflected all the traditional, Route One virtues of manhood. It was a period when men had started to consume in ways they never had before, embracing designer lifestyles that had hitherto been denied them. Whether the GQ reader was an architect or a banker, whether he had spent his formative years reading The Face and Arena or the Guardian or the Financial Times, in 1988 he found a place to rest his head – or, rather, a place to rest his Mont Blanc fountain pen, the keys to his Porsche 911 or the Soul II Soul CD (that place probably being a Matthew Hilton “Flipper” glass coffee table, complete with cast-aluminium shark fins masquerading as legs).

The GQ generation had ambition and self-fulfilment hard-wired into it from the get-go: and we liked it that way. We embraced the exercise boom as the body beautiful became a male ideal, and we all started to become educated consumers, consuming more like women, in fact – the most sophisticated consumers of all. Some tried to label us New Men, but I don’t think many of us were comfortable being called feminist-influenced sexual revolutionaries (not in public, anyway). GQ was the manifestation of what we secretly knew to be true: we can have it all.

At least once a week I meet a journalist who has just been “let go” by a national newspaper, someone who has almost certainly had at least 25 years’ experience, but who will probably never have a newspaper staff job again.

As newspapers appear uninterested in spending money on anyone other than above-the-line columnists, so your average, well-educated, heavily experienced Fleet Street professional has become surplus to requirements. This means that there are a lot more journalists to choose from, although the content of the magazine is still largely decided by a very small team of men and women who are well versed in the issues of the masculine and the metrosexual, confessional and confident.

The trick, I think, is to trust your instincts always, to go with what you feel rather than what you think other people might want you to do. This is not an original thought, but it’s an important one. As Henry Ford once said, “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”

Like many other publications, GQ now exists in various different digital guises. Today we are even more aware that we’re not simply competing with other magazines, but with everything that passes in front of someone’s face, whether they’re in a newsagent, on a train, a plane, in a car, on a beach, or in bed. Is our customer reading a book, his iPad, his iPhone, his laptop? Is he watching a film, talking to his wife, embracing his boyfriend or girlfriend, reading a magazine, playing a game, or writing yet another scathing report on TripAdvisor?

We are fighting for space in a world where we have no right to expect anyone’s attention. Consequently we are working harder than we have ever worked before. I don’t think there has ever been a more exciting time to be in our industry, because we live in a world now of horses and motor cars. There are still a lot of people who think they can survive simply by riding faster horses. And they’re the same people who once believed in the New Lad.

Dylan Jones is the editor-in-chief of GQ

His latest book, “Elvis Has Left The Building: The Day the King Died” is published by Duckworth (£16.99)