Editor’s note: On 16 February 2024 Russian news agencies reported that Alexei Navalny had died in prison in the Arctic Circle, while serving a 19-year sentence on charges that many in the West consider politically motivated. As an opposition politician and activist, Navalny was one of Vladimir Putin’s most outspoken critics.

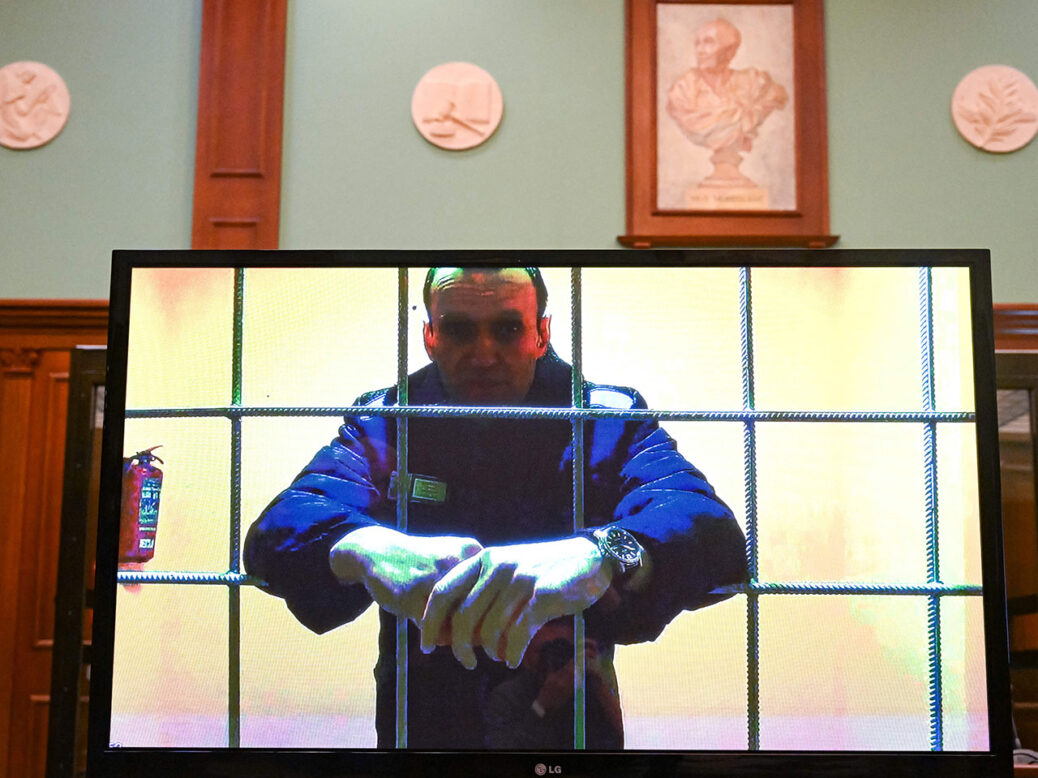

This month, a court based in a maximum-security prison in Melekhovo, 150 miles from Moscow, sentenced the Russian dissident Alexei Navalny to 19 years in prison on trumped-up “extremism” charges. One of his political directors in Siberia faces similar bogus charges, and is likely to receive an equally harsh sentence from judicial authorities determined to stamp out all opposition to Vladimir Putin and his war against Ukraine.

The news received by-the-numbers coverage in the Western media, and didn’t resonate at all in the wider public square. This was in stark contrast to the earlier Cold War and post-9/11 eras, when jailed dissidents such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Natan Sharansky, Aung San Suu Kyi, Liu Xiaobo and Ahmad Batebi, among many others, were treated as causes célèbre by millions across the world.

Chalk up the global dissident as the latest victim of the polarisation, disenchantment and internal decay wracking Western democracies.

Getting worked up about the fate of oppressed peoples “over there”, in benighted and repressive Asiatic places, dates to the age of European empire. Mass moral agitation in London or Paris over, say, the fate of Greeks and Balkan Christians under Ottoman rule was as sincere as the Sublime Porte’s brutality against such populations was real. Still, such sentiments also helpfully played into imperial geopolitics. Nor could the empire of liberty across the Atlantic resist the combination of hypocrisy and high moral dudgeon: the Jeffersonians, including the Sage of Monticello himself, Thomas, could summon greater outrage over the suffering of Europe’s embattled democrats than that of their own flogged and manacled slaves.

Yet the figure of the imperilled dissident – typically, an artist, activist or intellectual – is distinctly a phenomenon of the 20th century and, especially, of the Cold War. That’s when two rival branches of Enlightenment thought, liberalism and communism, faced off against each other in a global conflict with nuclear stakes. As important as closing the missile gap was winning the moral race, as each side sought to portray the other as backward and repressive.

In this race, the democratic West undoubtedly had the upper hand, and for good reason: while the Soviets could point to legal apartheid in the American South and other such crimes, it was they who starved millions, who staged farcical show trials, and who operated the gulag. Above all, it was the Soviet bloc that censored and sometimes imprisoned literary lights like Solzhenitsyn and Václav Havel – that targeted the Dissident.

Concern over the dissident trapped behind the Iron Curtain soon gave rise to a social apparatus aimed at spotlighting their plight. Organisations such as Pen America, Amnesty and Helsinki Watch (later to become Human Rights Watch) transformed dissidents into household names, at least among a middle-class set. The cause of Soviet refuseniks like Sharansky inspired one of the most moving expressions of mass American-Jewish activism in the postwar period.

Beyond cynical Cold War calculations, the popularity of the dissident reflected the relative cultural stability and material affluence of the West in the immediate decades after the Second World War. In those happier days, the dissident came to embody “our” confident self-conception in places where other peoples yearned to be happy – and free. This confidence, above all, had to be maintained. Which is why the dissidents found themselves marginalised when they veered off-script.

That happened most notably with Solzhenitsyn. When the exiled man of letters agreed to deliver the commencement address to the 1978 graduating class at Harvard, he knew what was expected of him: to sing an ode to “the great Atlantic Fortress of Liberty”, as he later confided. When he instead offered a stinging rebuke to the West, decrying its alienation and capitalist greed, the US press dismissed him as a zealot and a crank; his reputation never recovered.

With the Cold War over, the West’s dissident romance shifted back to the repressive orient. The 9/11 attacks focused attention on dissidents in the Middle East: young people with Western clothes, smartphones and aspirations labouring under the yoke of kleptocratic, often anti-Western dictatorships. Here was an incipient democratic elite prepared to rid themselves of ancient despotism and inaugurate the End of History in the House of Islam. As CIA black sites and “enhanced interrogation” proliferated, the Bush administration rallied to the Middle Eastern dissident’s cause. So did a host of liberal interventionists such as Christopher Hitchens and Paul Berman (and, in full candour, yours truly).

Yet here we are now, two decades later: the dissident’s star has fallen. What happened?

[See also: Only snobbery can stop Elon Musk]

Well, for one thing, the wars waged on behalf of democratic dissidents in the Middle East and North Africa were epic disasters, leaving state collapse, civil war and mass displacement in their wake. In countries like Egypt, meanwhile, the Arab Spring unhelpfully revealed secular dissidents to be outnumbered by pious Muslims with their own, and no doubt very different, democratic visions; the seculars were more than happy to restore secular strongman rule to abort Islamist democracy.

Then, too, the double standards of the human rights movement become glaringly unavoidable in an age of instant fact-checks and social-media pushback against all official pieties. Already, in the final years of the twilight struggle against the Soviets, more honest American Cold Warriors such as Jeane Kirkpatrick proclaimed that, yes, we should highlight the anti-dissident actions of the totalitarian east, while showing greater forbearance for anti-communist right-wing dictatorships.

In that context, the distinction between totalitarians and “mere” authoritarians made a good amount of sense (many of the pro-Western dictatorships would eventually evolve into liberal democracies). But in the post-9/11 era, things were more muddled: how morally different, really, were Syria and Bahrain? In both, a relatively small sectarian minority – Alawites in Syria, Sunnis in Bahrain – lorded over a disenfranchised majority – Sunnis in Syria, Shias in Bahrain. Yet the West made much ado about the one, while ignoring or playing down the suppression of dissent in the other. Pro-democracy “tweeps”, as they were once known, didn’t fail to spot the difference: Syria was (and is) allied with the Western arch-nemesis Iran, while Bahrain is a Saudi satrapy and host to some 9,000 US military personnel.

The Uyghurs’ Western reception gradually shifted, from a potential Islamist threat to hallowed victims of Chinese communist repression – a transformation that, conveniently, took place just as the rivalry between Beijing and Washington intensified. Also easily forgotten: Putin’s brutal Chechen policy once won him approval and accolades in Washington for its hard-nosed “anti-terror” approach. The alliance with Saudi Arabia made a mockery of 9/11 dissident politics.

Plus, the dissidents themselves rarely live up to their idealised image upon closer inspection. Once freed and in political office, Aung San Suu Kyi acted as an apologist for the Burmese state’s ethno-sectarian chauvinism. In his post-Soviet afterlife, Sharansky could appear in progressive eyes as just another parochial right-wing Israeli politician. There was discomfiting evidence that the murdered Saudi dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi, while unquestionably brave, had also been a Qatari agent of influence. Many an Arab secularist dissident turned out to hold views about Jews that were scarcely different from those of Islamists. Navalny professed decidedly unsavoury nationalist views and could at times outflank Putin – from the right.

But perhaps the most important factor in the decline of the global dissident has been the internal fracturing of Western democracies amid the rise of populist movements beginning in the mid-2010s. Movements like Brexit and Trumpism bitterly underscored that all was no longer happy and stable in the democratic heartlands; that while elites had been busy pursuing the politics of human rights and liberal expansion abroad, millions had been left behind materially at home. What did the name Khashoggi mean to the Rust Belt car worker pushed into wage, health and retirement precarity by the “blessings” of free trade?

In response, elite proponents of dissident politics damned themselves by suppressing populist dissent. When a decisive share of working-class voters propelled Donald Trump to the White House, this wasn’t treated as an opportunity to attend to the crumbling domestic hearth and to rethink the post-Cold War paradigms. No, for many who championed names like Navalny and Khashoggi, the insurgency called for Big Tech censorship, debanking and other efforts to roll back the populist tide. Suddenly, there emerged a class of people who viewed their own Trumpian and Brexiteering counter-elites as… dissidents. If this was sometimes ridiculous, the outrage was no less sincere and heartfelt than that mustered by liberals on behalf of Navalny.

But don’t mourn the global dissident. On balance, it’s a healthy development for the West to stop dividing nations “over there” into camps of demons and angels. Conducting foreign policy on the behalf of imprisoned angels tended not to end well.

[See also: How do you purge an elite?]