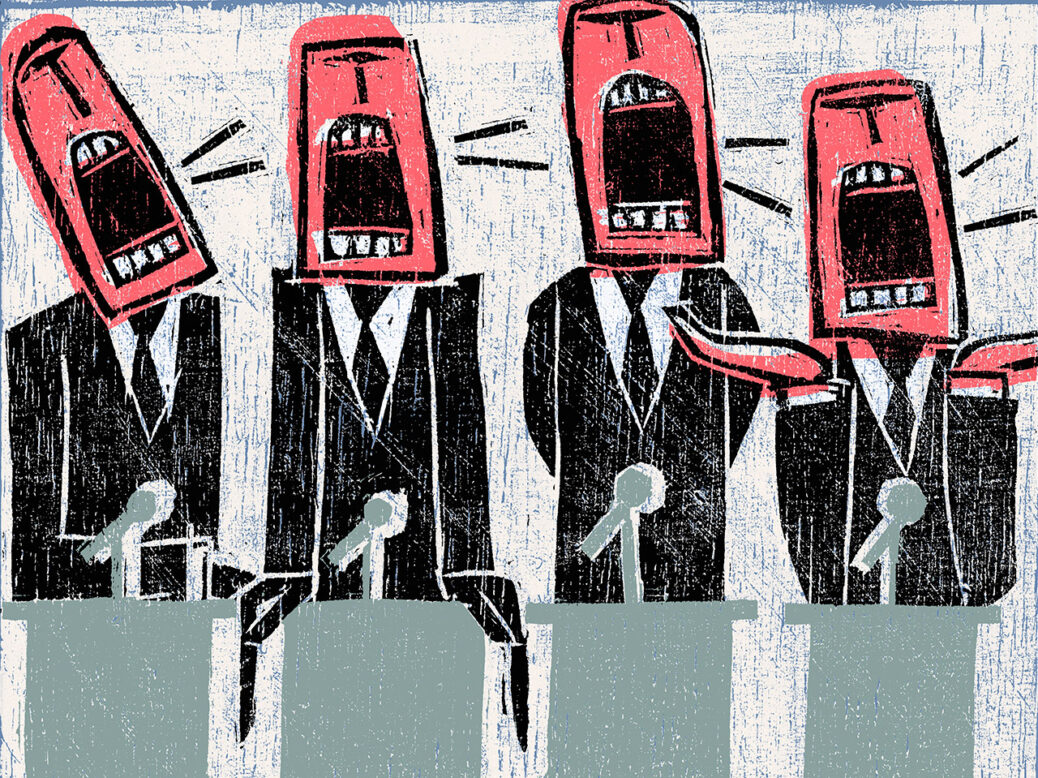

What I really wanted to do here was to make fun of some dads. Sometimes you do just have to be honest with your readers, so here I am. When I sat down to think about this week’s column, all I aimed to do was to gently lampoon some white middle-aged men, all of whom seem to have podcasts.

It all started when Ed Balls and George Osborne announced that they were launching a show together, to discuss the British economy and its many woes. It made me want to sigh until my lungs collapsed in on themselves. Do we really need them to join the fray?

We already have Rory Stewart and Alastair Campbell’s The Rest Is Politics, where Westminster frenemies offer the illusion of debate by occasionally, politely disagreeing with one another. Can’t any of them get real jobs? Speaking of which, why can’t someone – anyone – get Matt Hancock to stop posting on TikTok?

This is where my plan to be vicious but ultimately hollow over the course of roughly 800 words hit a roadblock. There is one quite obvious thing that all five men have in common: they all reached very senior positions in politics – cabinet ministers, shadow chancellor, Downing Street director of comms – but left said positions before even turning 50. What if the problem wasn’t their desire to keep rambling on about what they think? What if it was structural?

Annoyingly, it’s a theory that the data seems to back up. Between 1945 and 1955, the average age of cabinet ministers was 55 years old. In 2015, it was 50. Five years may not seem like a lot in the grand scheme of things but context is everything. In 1950, life expectancy was 68 years old; by 2015, it had risen by a whopping 13 years, all the way up to 81.

Though members of parliament probably weren’t, for the most part, the people dying particularly young, it seems fair to suggest that we now live better and longer lives than we did some decades ago. In practice this means that politicians (and their advisers) can today have fully fledged, successful political careers that still end about 25 years before they’re due to retire.

[See also: Alastair Campbell interview: “Boris Johnson and his kind should never be allowed near public life again”]

Because it is a fairly recent phenomenon, there is no road map for what they ought to do next. Not every cabinet minister will end up in the House of Lords, as they used to, and not every former frontbencher will want to haunt the back benches until they shuffle off this mortal coil. As the outraged reaction when Nick Clegg joined Facebook in 2018 showed, there are also a number of jobs which are deemed to be unseemly for one-time MPs to take.

Getting a regular gig may not be straightforward either. Being an MP means having a working life that is unlike any other job, with no boss to speak of, some whimsical working hours, and a degree of freedom to set your own schedule and just do what you like – which few offices can offer. Having spoken to my fair share of former parliamentarians over the years, I can say with a level of certainty that the return to civilian life is rarely smooth.

Of course, there is also a personality problem. Becoming not only a politician but a senior figure in government or opposition means learning to be comfortable with a degree of public attention – or, for some of them, even revelling in it. As a columnist, sitting in my big, beautiful glass house, it isn’t really a trait I can mock.

To say I have sympathy for the terrible, heart-wrenching plight of former cabinet ministers in search of a way to fill 20 or 30 years of working life would be pushing it. Still, it seems worth wondering if we should have a proper conversation about what we want them to do in that time. We, as a people, do not like it when they leave parliament and take some slightly dodgy corporate gig in order to swim in a pool of cash. We object to them becoming lobbyists and frown at some of them becoming peers. I, personally, find it tedious when they start hosting podcasts.

So what do we actually want them to be doing then? There is no point in climbing on our collective high horse and demanding that they spend decades quietly doing charity work, or something suitably hair-shirty. We can only work with the politicians we have, not the ones we think we deserve. Obviously a lot of them will want money, prestige and attention – they never would have made it to parliament in the first place otherwise.

If we are to have a political culture in which people are chewed up and spat out by the time they reach middle age, we have to accept that many of them will have very public second acts. In the long run, I just hope that, one day, when it comes to the media industry, “your dad and his mate drone on for a while” stops being such a bafflingly successful formula.

[See also: Are British prime ministers too powerful? With Armando Iannucci | Westminster Reimagined]