As the NHS turns 75, it’s hard to avoid thinking of Britain as “a national health service with a country attached”, just like the British economy is “a property market powered by the City of London with poor regions attached”. The UK is becoming increasingly fragmented even as we clap for carers and celebrate national institutions such as the monarchy or the armed forces.

It is not just the Union that is under huge strain, nor our politics across the four nations that has become more polarised. The country’s social fabric is unravelling, as evinced by a marked decay in the relationships and institutions that make up everyday social life. There’s divorce, family breakdown and more children born outside of stable relationships. The UK is fast going the way of the US, where more people live alone today than at any point in the country’s history, with 30 per cent of households consisting of one person only. Like America, Britain faces a pandemic of loneliness.

A study by the British Red Cross a few years ago found that 9 million people in the UK felt lonely. And that was before Covid-19 struck. Increasing isolation is hitting the most vulnerable hardest, especially older people but also the younger generations. This could have devastating consequences for their physical and mental health.

We also know that fewer people are members of local groups, or are volunteers, or engage in community activities. All this reduces levels of social trust and the communal cooperation on which democracy depends – our ability to build consensus and nurture the political norm of loser’s consent, such as peaceful transfers of power. Little wonder then that popular belief in democracy is falling, especially among the young.

In 2022 the centre-right think tank Onward found that 61 per cent of 18-34-year-olds agreed that “having a strong leader who does not have to bother with parliament and elections would be a good way of governing this country”, while 46 per cent of 18-34-year-olds agreed that “having the army rule would be a good way of governing this country”. Social atomisation boosts support for authoritarian strongmen.

[See also: Why public services will fail without tax reform]

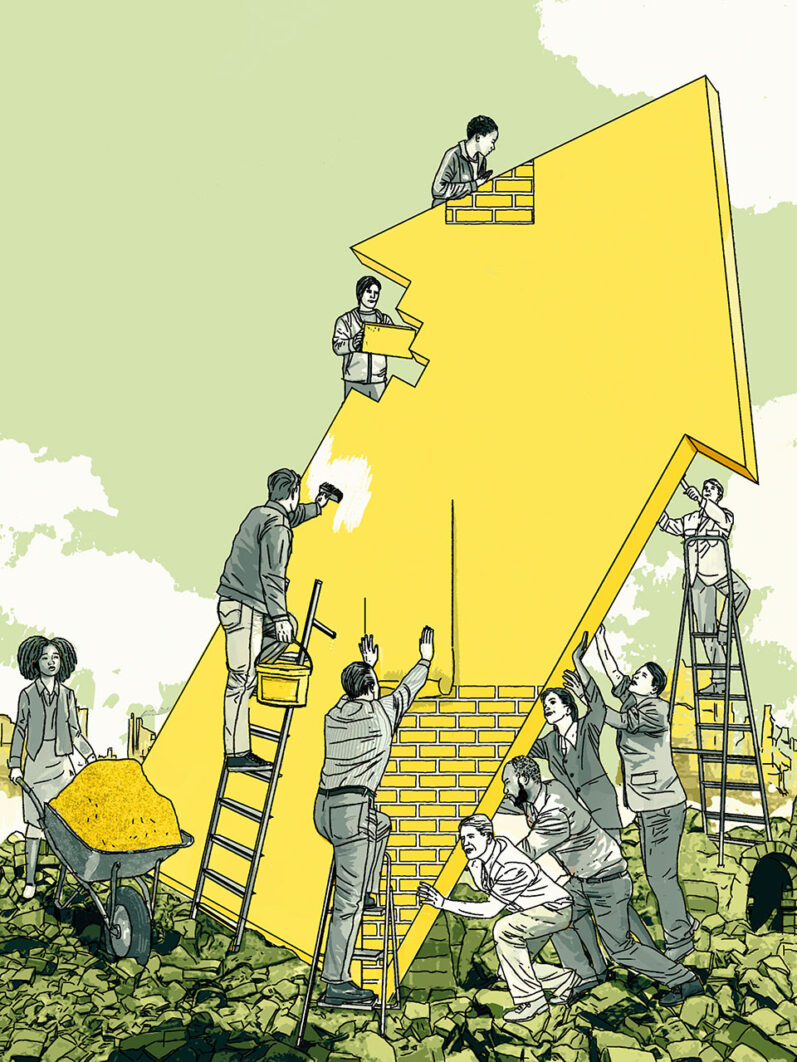

What is to be done? Political reforms alone cannot reweave the social tapestry that is being torn asunder. As a country we need to rebuild social bonds in a context where mass membership of political parties, trade unions and institutional religion has collapsed. As a result, people from different social classes, ethnic backgrounds and cultural traditions coexist but are often segregated in terms of housing, schools and community life. Sports clubs and the army are the exceptions that prove the rule.

If you add the lethal mix of narrow social networks, overprotective parenting, meaningless (“bullshit”) jobs and online connections trumping real relationships, then we are arguably a nation of strangers – not neighbours or fellow citizens. Rampant individualism and a culture of consumerism have left us atomised and alienated from one another.

One way to renew social ties would be to introduce a year of national civic service for all adults. This could consist of two distinct strands: first, a national nature service, modelled on Franklin D Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), dedicated to cleaning up our polluted rivers, building flood defences, tree-planting, restoring biodiversity and domestic heating conversion. Roosevelt’s CCC was credited with improving the well-being and employability of young people – exactly what our labour market and our society need.

The second strand would be a national community service dedicated to helping understaffed hospitals and schools, teaching English to new arrivals, cleaning up graffiti and rebuilding communal space like village halls, playgrounds or parks which are often the target of anti-social behaviour. Social order is not the sole preserve of the police or the local council, but should be built by ordinary citizens in the places they call home.

A national civic service will of course only work if it is universal and compulsory, so that people from all class and cultural backgrounds can come together and associate around a common purpose – serving their communities and their country. Such a scheme would be designed in flexible ways to accommodate different needs.

For example, the unemployed would be offered work-like experience programmes, equipping them with skills and confidence to support their transition into employment – as with Australia’s Work for the Dole programme. In the latter, people without a job can get involved in their local community and gain a licence or work towards a professional qualification in exchange for a more generous allowance than the current, miserly job-seekers’ allowance – what they call a “mutual obligation requirement”. Similar arrangements would apply to the retired, those who take a career break and those who want to retrain. They would be able to do their year of compulsory service at different moments in their lives and take on tasks adapted to their circumstances.

Of course all this needs funding and institutions to deliver it, which in turn requires political will. It’s time our politicians rose to the task. If Britain was capable of building the NHS and the welfare state after two devastating world wars, now is the moment to create a National Civic Service.

In our state of chronic emergency, sticking to the status quo means we face the frightening prospect of sliding into an ever-more atomised society and authoritarian politics. It doesn’t have to be that way.

[See also: Can the NHS workforce plan rescue the health service?]