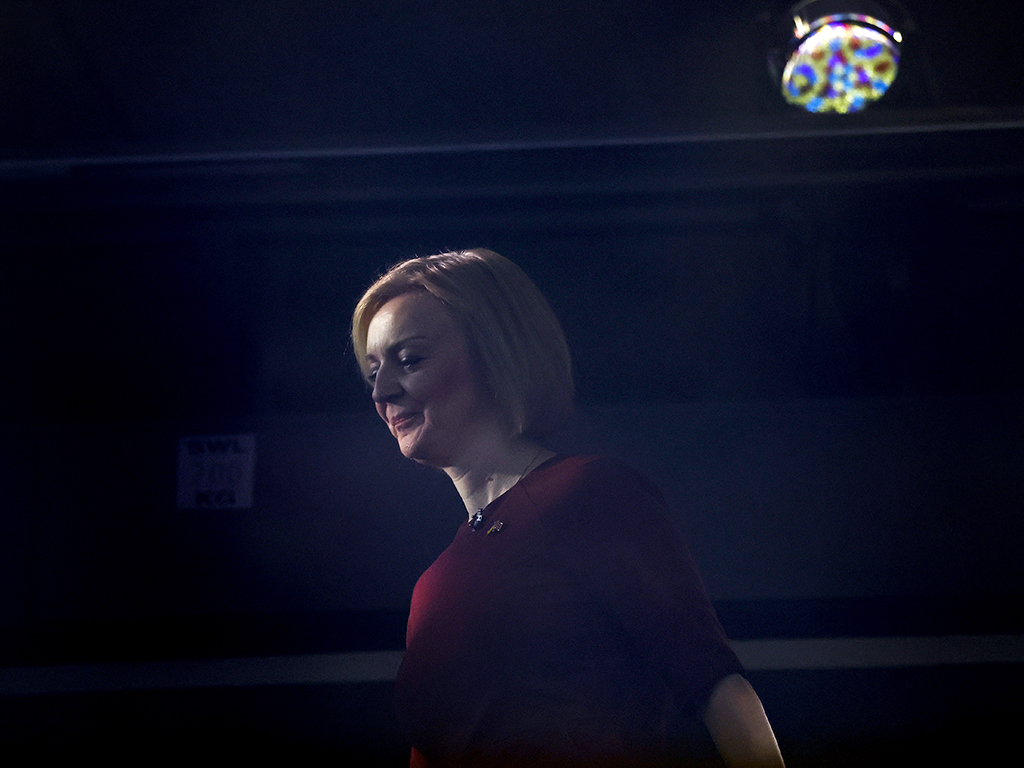

It is one of the great ironies of this new political period. The forces that brought us this government began as a revolt against an out-of-touch establishment, concerned only with pleasing a privileged slice of the electorate at the expense of everyone else, and arrogantly presuming to know what was best. They have resulted in Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng’s mini-Budget.

The post-Brexit Tory party has ditched many things that we associate with its pre-Brexit version – political caution, fiscal responsibility, respect for experts – but under Truss it seems to have resurrected one of its biggest flaws: an appearance of disdain towards swathes of the electorate. Truss, who owes her career to Brexit, has forgotten Brexit’s only important lesson. Don’t ignore ordinary voters.

This really matters. Appearing not to have contempt for your voters is what you might call, in politics, very basic stuff. It is not clear, however, that Truss quite knows this. Despite her U-turn over the abolition of the 45p tax rate, she resembles someone determined to barrel on with her plan, no matter what polls suggest the public may think, and no matter what their elected representatives in parliament may want. She is prepared, as she told Sky News’s Beth Rigby last month, to be an unpopular politician.

We attach a sort of virtue to unpopularity because we tend to associate it with individuals standing up for their principles in the face of pressure. Truss’s statement to Rigby was greeted with a certain amount of respect from colleagues and commentators. After all, a continuing criticism of prime ministers from Tony Blair to Boris Johnson was that they were overly preoccupied with their popularity – anxiously making use of focus groups and polls, and routinely changing course to avoid displeasing the electorate. It is easy to be scornful of the pursuit of popularity because it projects a lack of confidence.

But unpopularity is overrated. Consent from the public is where democracy starts. It is not virtuous to prioritise your own preferences over those of the people who voted for you – in fact it is a dereliction of your duty. Governments can lead, but they must also persuade the public to follow them. It is not democratic to try to impose your plans on an unwilling electorate, no matter how much cleverer you think you are.

As a leader who has not been directly chosen by the public, it is even more incumbent on Truss to engage with them and win their support for her policies. Instead she and her Chancellor are giving off a strong whiff of arrogance. Nobody likes them, and they don’t care.

Truss’s predisposition to this mistake is clear from her political past. Unlike her main leadership rival Rishi Sunak, her tenure in important government jobs was unmarked by the need to compromise. As chancellor, Sunak found himself raising taxes and unleashing a vast spending programme despite his small-state instincts; Truss, as international trade secretary and later as foreign secretary, rarely had to chart a course she didn’t believe in. The biggest lesson she has drawn from her career, in which she made a number of missteps only to bounce back every time, is to always trust her gut. At the outset of the Tory leadership election, Truss faced unpopularity among Tory MPs and a dismal reaction from audiences to her TV debates appearances. It did not matter.

But as a leader, unpopularity simply does not work as a strategy. A concern with being liked by the public was not Johnson’s problem, and not why he eventually fell from power. His problem was that he was only concerned with the approval of a certain, narrow slice of the electorate and was insufficiently interested in gaining consent from the rest. His failure to impose a lockdown soon enough during the Covid-19 pandemic was not born of excessive concern for what people thought, but a lack of information. People had been willing to lock down. He had misread them.

Truss’s stance on popularity will not be tolerated for long. In a democracy, public reaction does matter, in moral and practical terms. Truss’s mistake will be remedied – if only at the next election in 2024 (which is not all that far away now). It should be remedied before that.

[See also: How long can Liz Truss survive?]