There is a policy that would, at little or no cost to the Exchequer, increase the sum of human happiness in the nation – because it would have made this week, and those that follow, so much less anxiety-laden for thousands of students and their parents. In the wake of exam-result Thursday, we now ought to abolish the GCSE. The UK is in a small minority among developed nations in having public examinations at 16. Few nations divide their student populations as we do at that age. It’s time we stopped. And that should be just the start of what we do with education.

The original School Certificate, which is the distant ancestor of the GCSE, catered for a world in which most pupils left full-time education by the age of 16. Since its abolition in 1951, British education has veered between separating students and binding them together. The O-level, which replaced the School Certificate, was split in two in 1965 when Harold Wilson’s government introduced the Certificate of Secondary Education (CSE) for the less academically able portion of the cohort. In 1986 Margaret Thatcher’s government put the pieces back together again with the creation of the combined General Certificate of Secondary Education, with pupils sitting the first GCSE exams nationwide in 1988. But it’s never really worked for everyone.

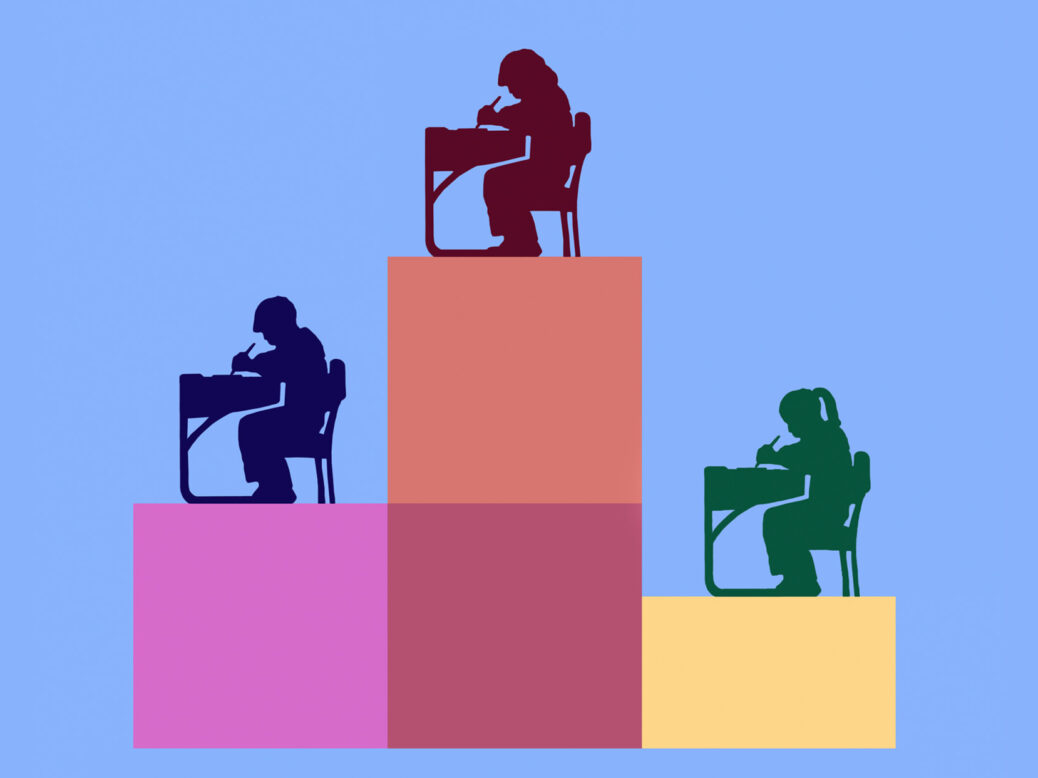

The GCSE is fine, though unnecessary, as a signalling device to separate those who are going on to do academic A-levels from those who are not. But every year something in the order of 100,000 pupils do not get five “good” GCSEs – defined as grade 5 or above, and considered to be the basic necessary standard – or the equivalent technical qualifications. Most of them will be from working-class backgrounds. They will have gone through their education and effectively been marked as a “failure” at the end of it. Before students can embark on a path to which they are suited, we force them to fail.

[See also: Tony Blair is right: more people should go on to higher education]

This is part of the reasoning that informs some radical suggestions for reform published on 23 August by the Tony Blair Institute (TBI). Education, argued the TBI report, is staying fixed while the world of work is changing rapidly. The school curriculum, it goes on to say, is not organised to foster the critical and persuasive skills that students now need as they emerge from education into work. Time was when the school gates closed behind a young man (as it usually was then) and the factory gates opened to let him in. Today, we are failing too many students with an education that doesn’t match the times. So, abolish the out-of-date GCSE and replace it with continuous – but internal – assessment.

In a thoughtful piece for the Institute for Government, Sam Freedman, a former education adviser to Michael Gove (and an NS contributor), makes the valid point that upheaval has costs as well as benefits, and that the GCSE does a good job in concentrating students’ minds on valuable information. Radicals should always halt and take the conservative objection seriously – but surely in the UK we can, as other nations do, provide a valuable education without the need for a public examination at 16. The pertinent question might be this: if we did not have the GCSE, would we invent it? It is hard to imagine what problem it would be designed to solve.

What it does achieve is to split the pupil population along academic lines. On 18 August, an older cohort of nervous students received their A-level results. The TBI wants to be shot of the A-level too, on the same grounds: that it looks backwards to a world before artificial intelligence and automation. The more potent critique of the A-level is that not enough people do it. Well over half of British 18-year-olds were not worried about their A-levels on results day, because they hadn’t taken them*. This points to the greatest deficiency of all in the UK education system, which the annual obsession with GCSE and A-level results barely begins to touch. As a country we provide a world-class education for the highest-achieving students, but nothing of a comparable standard for their able but less academic peers.

[See also: You don’t win over young people by blocking their access to education]

The reason for this is written deep into the history of British education. Rab Butler’s 1971 memoir The Art of the Possible is one of the best reflections on being a senior politician in the genre, but that didn’t stop his later biographer Anthony Howard giving the book a stinking review for being blind to the failure of the 1944 Education Act that Butler introduced. The “Butler Act” established three tiers of institution – grammar schools, technical schools and secondary moderns.

With the benefit of hindsight we can see that there were two fatal errors in Butler’s system. The split between grammars and secondary moderns condemned a generation of school children to an education that was widely seen as second class.

Butler’s second mistake was even greater. The technical schools failed to materialise. While grammar schools and comprehensive education dominated the debate thereafter, the technical institutions were quietly forgotten. There have been endless half-hearted attempts to boost vocational educations over the years, but it is hard to think of a minister who ever took that job especially seriously. It is still early days for the new post-16 T-level, which began in 2020. Students take a two-year course – with both theoretical and practical aspects, and a work placement – in subjects such as design, surveying and planning.

T-levels need to be given a chance to bed in. They have been devised with the full collaboration of employers, so it is not foolish to wish they succeed. Let’s hope they do, because radical reform, as Sam Freedman reminds us, is politically hard. Indeed, nobody knows this better than Tony Blair himself. In 2004, a former chief inspector of schools, Mike Tomlinson, conducted a major review of the curriculum, which recommended a four-part diploma for 14- to 19-year-olds, to replace the existing system. It was an attempt to include everyone in a single structure while permitting the specialisation necessary to respond to the variety of talents. When this idea reached the prime minister he instantly responded that abolishing A-levels just before a general election was poor politics.

Any serious change will have to await the new government. The Tory leadership contest continues to throw off policies on which no thought has been expended. Both candidates blithely endorsed grammar schools – the indestructible cockroach of Tory prejudices. Liz Truss then went a stage further with an odd proposal that Oxford and Cambridge should be forced to interview all candidates with three A* grades at A-level, which would require the ancient universities to conduct about 13,000 interviews per annum.

It used to be the case that Conservative politicians created a reputation in the Department for Education. Butler, of course, created the 1944 act during the wartime coalition. As education secretary, Margaret Thatcher closed more grammar schools than any Labour counterpart. Keith Joseph picked up a policy left by Shirley Williams and created the GCSE. Kenneth Baker established the national curriculum. Michael Gove greatly expanded the academy schools programme.

But since Gove was forced out of the job by Lynton Crosby in 2014, there have been a further seven secretaries of state for education. Trying to name them all is a parlour game of ineffable dullness. The turnover shows the lack of seriousness with which the government has lately treated the brief. From 1986, when Kenneth Baker began his tenure, to the end of Gillian Shephard’s in 1997 there were just five ministers. In 13 years of Labour government there were six. The Tories have got through eight in 12 years and one of them, Michelle Donelan, only lasted for 36 hours. At that rate, a week really is a long time in politics. We have, in fact, been waiting three quarters of a century for an education system that matches the times.

*This article was updated on 5 September 2022 to reflect accurately the number of A-level students compared to GCSE students in the UK (275,960 and 622,350 respectively, according to Ofqual figures for 2022).

[See also: Keir Starmer’s energy strategy hints at Wilson-like cunning]

This article appears in the 24 Aug 2022 issue of the New Statesman, The Inflation Wars