When the 51-year-old business development manager Rachel Elwell received a message from a stranger on New Year’s Day 2021, she did not envisage that she would lose her life savings to a man she had never met.

She had joined Facebook Dating during lockdown, after her sister and friends convinced her to give online dating a go. She was living on her own in Coventry and working from home, and while she wasn’t set on finding love, she wanted to meet someone new.

“I didn’t have any expectations and was quite happy being independent,” she told me. “But equally, I thought it would be nice to chat to people.”

On 1 January, she received a message from a man she had “matched” with called Stephen. “He looked like quite a happy, friendly person in his photos,” she said. “And he lived within 25 miles of me, a reasonable distance if we were to meet up for coffee.” They soon hit it off. They both liked dogs and dancing, and she was moved by his story – he had been widowed seven years ago and had raised his teenage daughter alone.

After three weeks of talking, Stephen asked Elwell for money; he said he had secured an engineering job in Ukraine and needed a few hundred pounds to tide him over after receiving an unexpected tax bill related to this work. She was suspicious, but he said he had no family to fall back on and reassured her that he would pay her back. “He groomed me with his backstory,” Elwell told me. “I had empathy for him and his daughter. He was so clever and manipulative.”

Stephen’s lies became more elaborate. At one point, he claimed that he was being held hostage by Russian loan sharks and that they would kill him if he did not pay. Elwell took out multiple loans to help him, feeling personally responsible for his life.

Over the next few months, she gave him £113,000.

Alarm bells started ringing when Elwell arranged to meet Stephen at Heathrow Airport and he never arrived. He claimed that he had been held for ransom by Ukrainian airport officials. On 1 April, three months after they had first spoken, the façade finally came down when Stephen arranged for his housekeeper to meet Elwell at his home in Coventry; when Elwell got there, the inhabitant had no idea who Stephen was.

“That’s when I realised it was all a lie,” said Elwell. “It felt like the world was closing in. I wasn’t heartbroken – it was relief, followed by despair that I was financially ruined.”

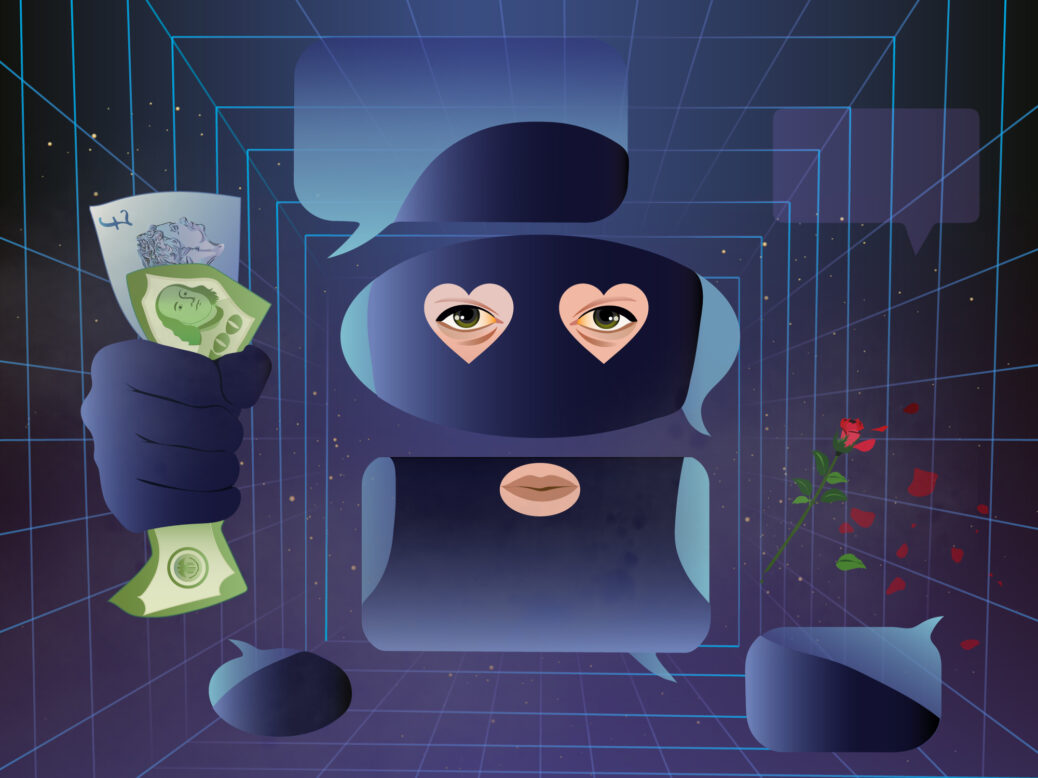

The rise in online dating, and lockdown loneliness, have led to a surge in romance scams. More than a third of people who have dated online have been asked for money, according to one survey, and data from the trade body UK Finance shows that in the first half of 2021, £15.1m was paid out to romance scammers, a 62 per cent increase on the amount paid out during the first half of 2020.

Elwell said that the incident left her feeling suicidal. She is currently taking antidepressants and receiving counselling.

“Romance scams can be particularly cruel,” said Pat Hurley, the lead ombudsman at the Financial Ombudsman Service. “The impact for victims can be huge and lead to a complete loss of trust and faith in other people.”

Such scams also create a complex problem for banks. When financial institutions raise concerns over a customer’s unusual payments, some victims have already been so manipulated that they ignore these warnings. Banks are torn between duties to carry out a customer’s wishes, and to act in the customer’s interests and block payments they believe to be unlawful.

Ed Fisher, head of fraud policy at Nationwide, said that addressing romance scams with victims can be very difficult. “You could be unpicking a relationship that that person believes they’ve been having for a year or two,” he explained. “After a ten-minute conversation, they’re not going to necessarily accept and absorb everything.”

But victims and their representatives say that banks should be doing more. Elwell is not eligible to be reimbursed for the money she has lost. Of the £15.1m lost to romance scams in the first half of last year, just over a third – £5.3m – was returned to customers.

Most major banks are signed up to the Contingent Reimbursement Model (CRM), a voluntary code that reimburses victims of romance scams and other authorised push payment fraud (APP, where the victim makes the payment themselves). Victims are more likely to be reimbursed if the bank did not give them sufficient warning, if there was a “reasonable basis” to believe the transaction was genuine, and if they could be deemed “vulnerable” due to their personal circumstances, their “capacity” to protect themselves, or the timing or nature of the scam. Banks will automatically assess APP scams against the code to decide whether a case meets the criteria for reimbursement. If it does not, victims can take their case to the ombudsman.

Outcomes differ depending on the case, said Fisher. For example, a widower dating for the first time would likely be seen very differently to a young person who has been online dating for years.

Elwell argued that this approach amounts to victim-blaming. “If you are a victim of mugging, you don’t expect the police to ask you, ‘did you put up a fight?’,” she told me. “You are made to feel by these banks, and under the CRM code, that you are the criminal.”

Both of Elwell’s banks, Santander and HSBC, are signed up to the CRM but have refused to reimburse her on the basis that she proceeded with payments despite their fraud warnings. She said they did not intervene quickly enough, question her rigorously enough, or communicate sufficiently with each other: after Santander stopped an international payment of £30,000, it allowed her to transfer that same sum to her HSBC account, which authorised the payment instead.

Her payments were also not eligible as they were made to a Ukrainian bank account and the CRM does not cover international payments, despite many fraudsters operating from overseas.

In a statement, Santander said it had “the utmost sympathy” for Elwell but that it had “repeatedly warned her of the dangers of transferring money to someone she hadn’t met”, and had raised concerns with both her and the police. HSBC said it was “sorry to hear that Ms Elwell has been the victim of an APP scam” but that it had “fulfilled its responsibilities under the CRM code”.

Elwell believes that firms should be communicating with each other more to protect vulnerable customers, and that staff should undergo better training to help them identify victims. Some banks do have mandatory annual fraud training for staff. The Banking Protocol, introduced across the industry in 2017, also requires banks to train their branch staff to spot the warning signs of scams and call the police. The scheme has since been extended to cover telephone and online banking, and was estimated to have prevented fraud worth £32m in the first half of 2021.

But Elwell believes there needs to be a greater emphasis on teaching bank staff to employ sensitivity and empathy towards vulnerable people. The Financial Ombudsman Service appears to agree with her. In 2020, it concluded that CRM-signatory banks are “inappropriately declining reimbursement”. It said many are not recognising the emotional manipulation involved in scams, are expecting too high a degree of caution or knowledge from victims, and are overestimating the efficacy of generic pop-up warnings.

Many believe that the focus needs to be on early prevention. “The real goal is to stop the crime in the first place,” said Nationwide’s Fisher. “Focusing on reimbursement alone doesn’t stop the terrible experience for the victim, and it certainly won’t stop the criminal receiving the proceeds.”

At present, most banks use automated scanning systems, employ staff to scan for suspicious transactions and call customers to check payments. Payment limits and pop-up warnings – including when the bank details do not match the payee’s name – are also all intended to stop fraud before it happens, while several banks have started using warnings that are personalised with the customer’s name.

But evidently, more needs to be done – and many believe that tech companies need to play their part. Fisher said that better data-sharing between social media firms and banks would help both industries catch suspicious conversations early. Jason Costain, the head of fraud prevention at NatWest, believes there should be more rigorous vetting of anonymous accounts, which are frequently used by scammers. “It is far too easy to set up a fake profile online,” he said.

He also thinks the police need to be better equipped to deal with fraud: local police forces lack resources, while centralised services such as the Dedicated Card and Payment Crime Unit (DCPCU) focus primarily on large money-laundering cases.

At present, only a small number of fraudsters are prosecuted: 5,835 arrests were made in England and Wales in 2021, despite there being nearly 876,000 reported scams.

More public campaigns would also help to raise awareness and destigmatise victims, added Samantha Cooper, founder of the private investigation firm Rogue Daters. The Office for National Statistics estimates that 85 per cent of fraud cases are not reported. “People don’t know the real numbers because most victims don’t report it and not enough people tell their stories,” she said. “There is a lot of victim-shaming. But the only crime people are guilty of is being kind and trusting.”

Elwell said that the stigma surrounding victims has caused a best friend of 20 years to abandon her. “I’m not ashamed or embarrassed because I behaved as an honourable person and did what I believed was the right thing,” she added. “People have got to stop this [shaming] because that is why people suffer in silence, and why many people commit suicide. Fraud will continue to touch more people than any other crime because of the cyber world that we live in.”

[See also: The NFT bubble looks ready to burst]