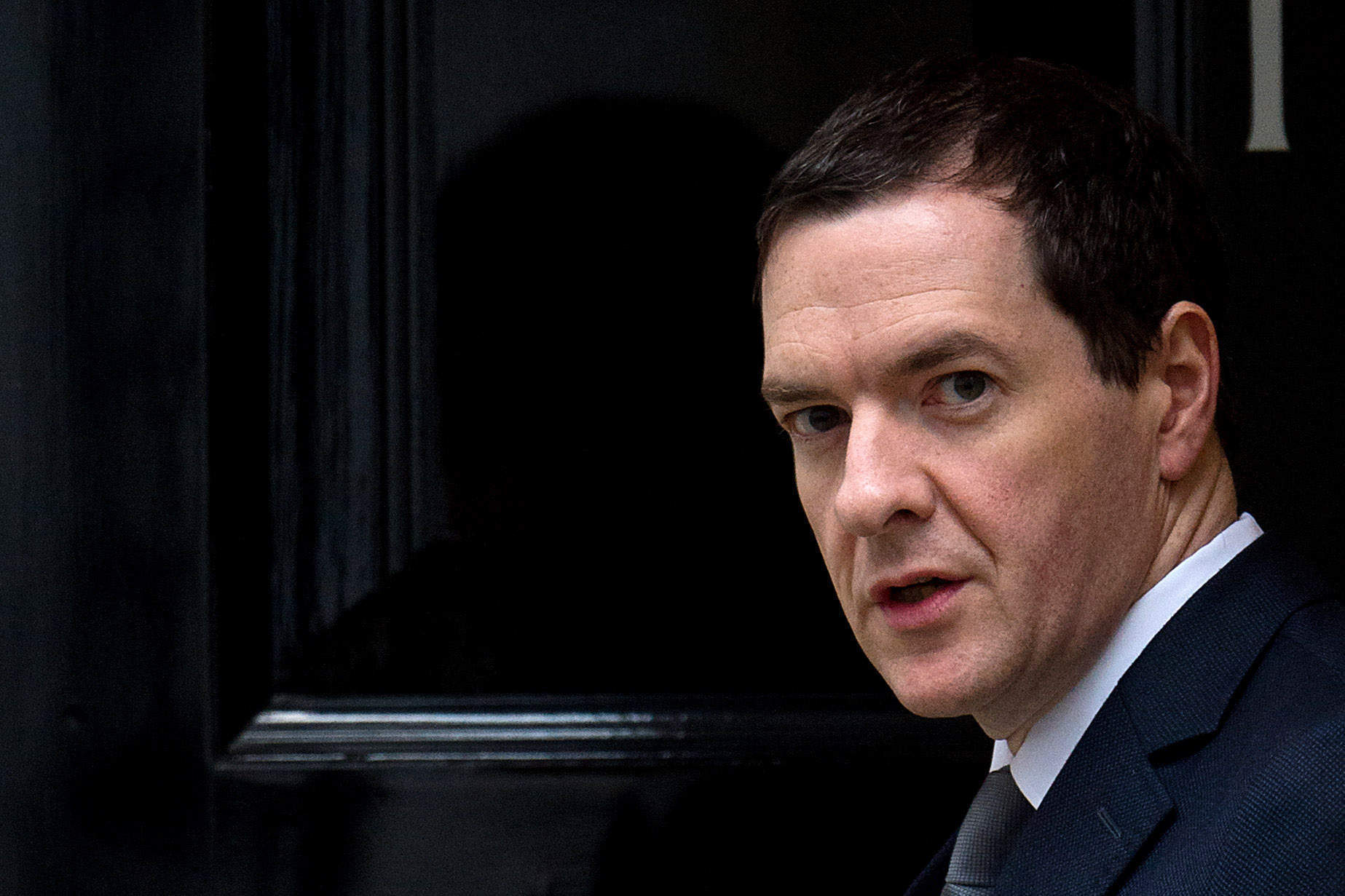

At last year’s Conservative conference in Manchester, Tory MPs spoke confidently about the identity of their next leader. “It will be George,” many predicted. Boris Johnson, the Chancellor’s chief rival, was said to have been marooned by the Tories’ unexpected majority in the general election a few months earlier. Osborne, David Cameron’s anointed successor, had a clear path to victory.

Almost six months later, the roles have been reversed. It is Osborne who is marginalised, while Johnson is heir apparent. The Mayor of London’s support for EU withdrawal has propelled him to a 13-point lead among Tory members in the most recent ConservativeHome poll (with a 33 per cent share). Ahead of his eighth Budget on 16 March, Osborne is in fourth place with 11 per cent, behind the Brexiters Michael Gove and Liam Fox. As recently as last October, he was leading by 15 points.

After the nadir of his 2012 “omnishambles” Budget, Osborne’s stock rose in line with the economy. The Tories’ election victory, for which he shared credit with Cameron, extended the surge. Yet a succession of events has now triggered a sell-off. Osborne’s U-turn on tax credit cuts was welcomed by Conservative MPs but was unavoidably wounding. His description of the Google tax deal as a “major success” left him politically isolated, including by No 10. His co-leadership of the EU renegotiation further reduced his standing. The decision of nearly half of Tory MPs to back Brexit both reflects and reinforces Osborne’s diminished status. His pre-emptive retreat over cutting pension tax relief was the political equivalent of an emergency share buy-back.

Osborne, colleagues say, has never been “personally popular” among Tory MPs. The Chancellor’s advance rested on patronage (to the benefit of the FOGs – “friends of George”) and on his status as leader-in-waiting. His low poll ratings risk exposing the shallowness of this support.

Tory donors are similarly uncharmed. “George is very boring, very tedious, a very cold personality,” the Ukrainian-born energy magnate Alexander Temerko told me recently. “We need a very warm, very bright leader . . . I talk to many donors and they’re ready to support Boris. He’s much more electable than George.”

Tory MPs regard Osborne’s reduced stock as an overdue market correction. His success was never as inevitable as it appeared in 2015 in the heady days of his China tour and his visit to Faslane in Scotland. Nor, they add, is failure now as certain as some suggest.

Osborne’s leadership hopes first depend on the UK voting to remain in the EU. No Tory MP I spoke to believed that he could win a post-Brexit contest. The upcoming Budget will therefore avoid any move that could sharply antagonise voters in advance of the 23 June vote. A reduction in the top rate of income tax from 45p to 40p, which he privately favours, has been ruled out. Downing Street’s strategic focus on the referendum has led to the junking or postponement of divisive measures such as tax credit cuts, a reduction in pension-tax relief and the approval of a third Heathrow runway (some view the new junior doctors’ contract as an unwise exception).

The Chancellor’s economic imperative of a Budget surplus (promised by 2019-20) is clashing with the political imperative of appeasing voters and Tory MPs. As a senior figure noted: “This is traditionally the time in the parliament when you do difficult things – the second Budget. You’ve had a chance to think through the circumstances and you’ve still got four years to recover.”

Osborne can draw comfort from the pro-EU side’s increased poll lead. The Leave campaign is no closer to answering the question that most believe it must in order to win: what happens after Brexit? Osborne’s allies are hopeful that Johnson will wilt like a salted snail during the campaign. “We are witnessing the slow making of George and the slow implosion of Boris,” one told me.

The risks – the unresolved migrant crisis, a low turnout of EU supporters – remain. At the Parliamentary Labour Party meeting on 7 March, the veteran MP Barry Sheerman’s cry echoed through the door of committee room 14: “Without the Labour machinery to get the vote out, we will lose! Jeremy [Corbyn], I beg you, get out there and show more passion to win the referendum.” His anxiety is shared by Downing Street, which fears that Labour’s low profile endangers the Remain side’s chances.

If defeat is averted, Osborne must hope that the economy, which his political fortunes have long tracked, continues to grow. Although the recovery may appear to be in its infancy, historic data suggests that the next recession is closer than the last.

Should Johnson’s popularity endure, Osborne’s best chance of securing the leadership is to prevent his rival from reaching the ballot (MPs preselect two candidates to go forward to the members). But one backbencher warned: “Everyone would see it as a George plot and he may well lose to the person who gets through. He’s damned if he does and damned if he doesn’t.”

If the odds are significantly against Osborne when Cameron steps down, Tory MPs suggest that he has enough “self-knowledge” and “detachment” to refrain from running. “He’s not like Gordon Brown, who was obsessed with it,” one told me. “George is more of a backgammon player. He regards it almost as an intellectual problem, as opposed to a prize which his life would be meaningless without.”

Not since Anthony Eden in 1955 has a Tory frontrunner become leader – and that status is now held by Boris Johnson, not the Chancellor. For Osborne, who has been near the top of his party for 11 years (no small feat), the game goes on. In less than a year, he has tasted triumph and disaster. He should treat these two impostors as just the same.

This article appears in the 09 Mar 2016 issue of the New Statesman, American Psycho