The fallout from the collapse into administration of Greensill Capital, the supply chain finance company that powered the growth of GFG Alliance, Sanjeev Gupta’s empire of steel and aluminium, has put thousands of jobs at risk and will have wide-ranging political fallout.

The SNP, which isn’t having the greatest month, looks bad because the Scottish government guaranteed Gupta that it would buy the electricity from a £330m hydroelectric power project in the Highlands for 25 years, a serious long-term risk for the taxpayer. The business department looks worse, because it allowed GFG Alliance and linked companies, via Greensill, to access pandemic support loans worth eight times the maximum allowed for any one company. A number of Tory MPs look bad for having gone on a cricket tour of Australia paid for by GFG.

[This Week in Business: get the New Statesman’s Monday read on the week ahead]

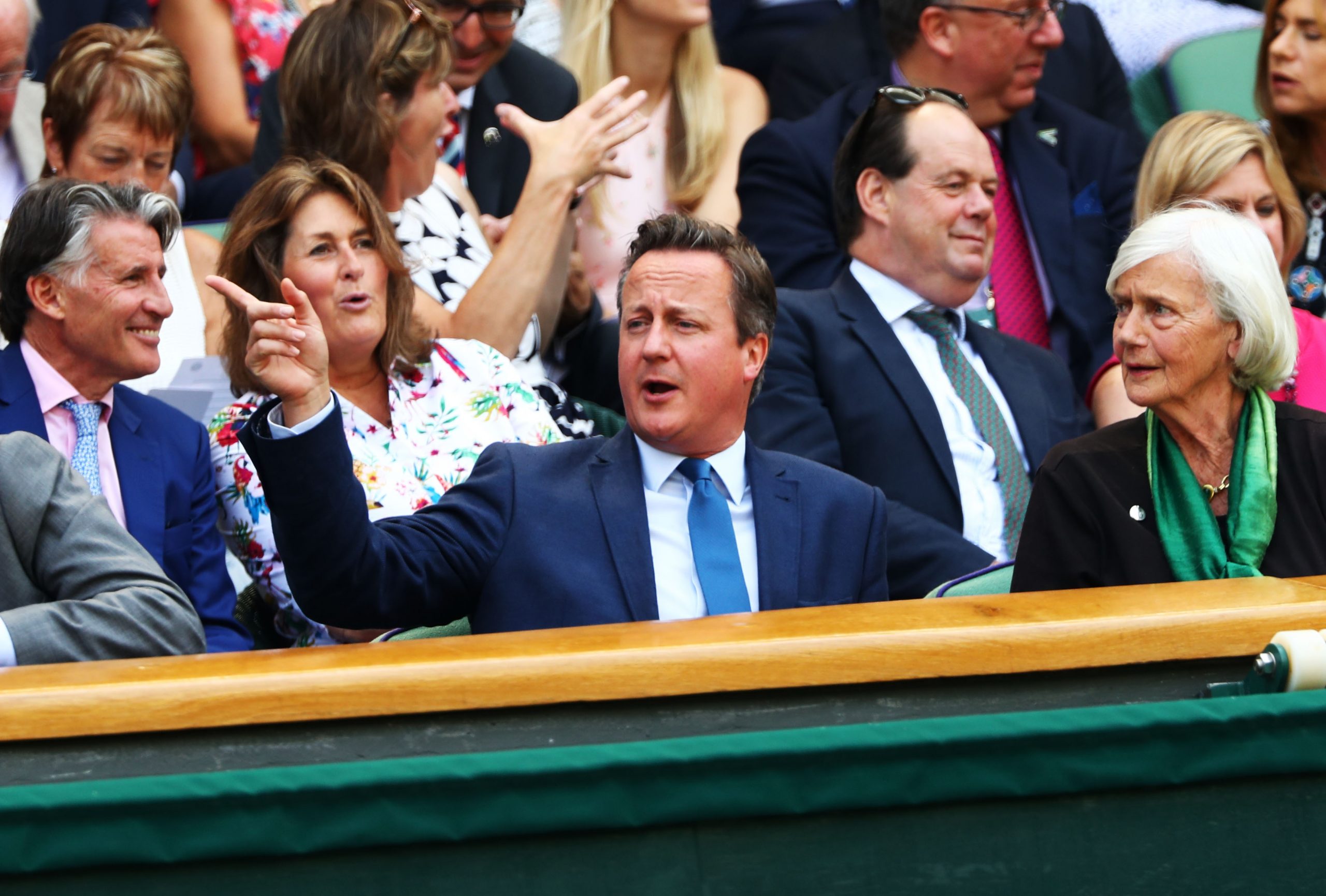

David Cameron, who in 2010 described lobbying as “the next big scandal waiting to happen” and “an issue that […] has tainted our politics for too long”, is reported to have lobbied the Treasury on behalf of Greensill for access to more government backing for its loans, sending multiple text messages to Rishi Sunak. Cameron is reported to have owned a significant quantity of shares in Greensill at the time. But the politician with the most to lose from the Greensill collapse is Sunak. In a less crowded news environment (and arguably in a different government), the revelation that a top Treasury official was prompted to continue hearing Greensill’s appeals “at the Chancellor’s request” would be hugely damaging.

[Hear more on the New Statesman podcast]

If Sunak emerges unscathed, it will be partly because his request for officials to hear Greensill out ultimately had no effect. Nor did Cameron’s lobbying; despite multiple meetings and – as sources have told the FT and the Sunday Times – personal email and phone communication from the former PM, Greensill was not allowed to join the Covid Corporate Financing Facility or extend bigger loans under the Coronavirus Large Business Interruption Loan Scheme.

If anything, the involvement of Cameron, Sunak, Nicola Sturgeon and others will mean that the fallout from Greensill’s collapse takes place in a particularly unforgiving spotlight. The shadow chancellor, Anneliese Dodds, has already called for an investigation into Cameron’s actions, and such calls will multiply if the government has to intervene to support GFG, which employs 5,000 people in the UK.

This should give the businesses that seek to benefit from high-level political connections pause for thought. In many cases such connections do little more than open a few doors, and such figures come with their own reputational risk.

Facebook is one example. When the company hired Nick Clegg as its head of global affairs it was at least partly buying Clegg’s many contacts in the EU, and especially his access to the bloc’s antitrust and digital policy chief, Margarethe Vestager. What Facebook may not have bargained for was the derision with which the appointment was greeted by a British public that still associates the former deputy PM with austerity and tuition fees.

Even the assistance of a serving minister can be of questionable value; Theresa May, as prime minister, wasn’t able to persuade the Saudi oil giant Aramco to list on the London Stock Exchange, despite visiting Saudi Arabia as part of the pitch. Matt Hancock was happy to promote Babylon Health as the newly appointed Health Secretary – speaking at its headquarters and even appearing in an advertorial for the company – but the company now has a lasting association with a minister whose competence and transparency have been questioned repeatedly over the past year.

Politicians themselves take a risk when they decide who to go into business with after they leave government. George “nine-jobs” Osborne may have been the butt of a few jokes for picking up roles but he seems to have made some astute decisions, enjoying both a prodigious salary at BlackRock (£650,000 for working one day a week) and a position of considerable power as editor of the Evening Standard. Cameron went to work for someone he already knew well – Lex Greensill was recruited by the Cabinet Office in 2014 as a “crown representative” to advise the Cameron ministry on government contracts – but whose business was fast-growing, complicated and risky.

The less risky option seems to be hiring government employees, rather than government ministers. Tony Close, Ofcom’s former director of content standards, was recently hired by Facebook. While there were some raised eyebrows, there was none of the public scorn that accompanied Clegg’s appointment – despite the fact that Close, as the author of much of the UK’s regulation on online harms, is the person best placed to help the company navigate that regulation.

But hoovering up too many civil servants also attracts attention. In 2011, the Royal Bank of Canada conducted a study (never published, but cited in Michael Lewis’s Flash Boys) which found that more than 200 employees of the Securities and Exchange Commission had been hired by high-frequency trading firms in less than five years. Regulating the predatory traders was off the table, Lewis argued, because so many of the regulator’s employees included them in their career path. There comes a point at which such activity begins to be seen not just as unseemly but as a significant problem that demands political action.

Political connections are not inherently wrong. MPs, peers and political advisers can help businesses without betraying their principles, and Cameron is – having left government six years ago – as free to work for businesses as anyone else. But calling in favours is a risky business and the public has no sympathy for anyone who gets their fingers caught in the revolving door.

[Get the New Statesman’s view on the week ahead each Monday at 6AM]