In 2006 I was a journalism student when I hit the work-experience jackpot: a month-long internship at Time Out, the magazine that for half a century embodied going out in London (and more lately New York, Paris, and a host of other cities).

To walk under its enormous neon sign, which projected confidently above the Tottenham Court Road, was to be catapulted back into the Swinging Sixties London in which the magazine had been founded: the office was all teak shelves, swirly yellow and brown carpets, and hungover journalists quietly recounting what they did last night (no one ever seemed to stay in).

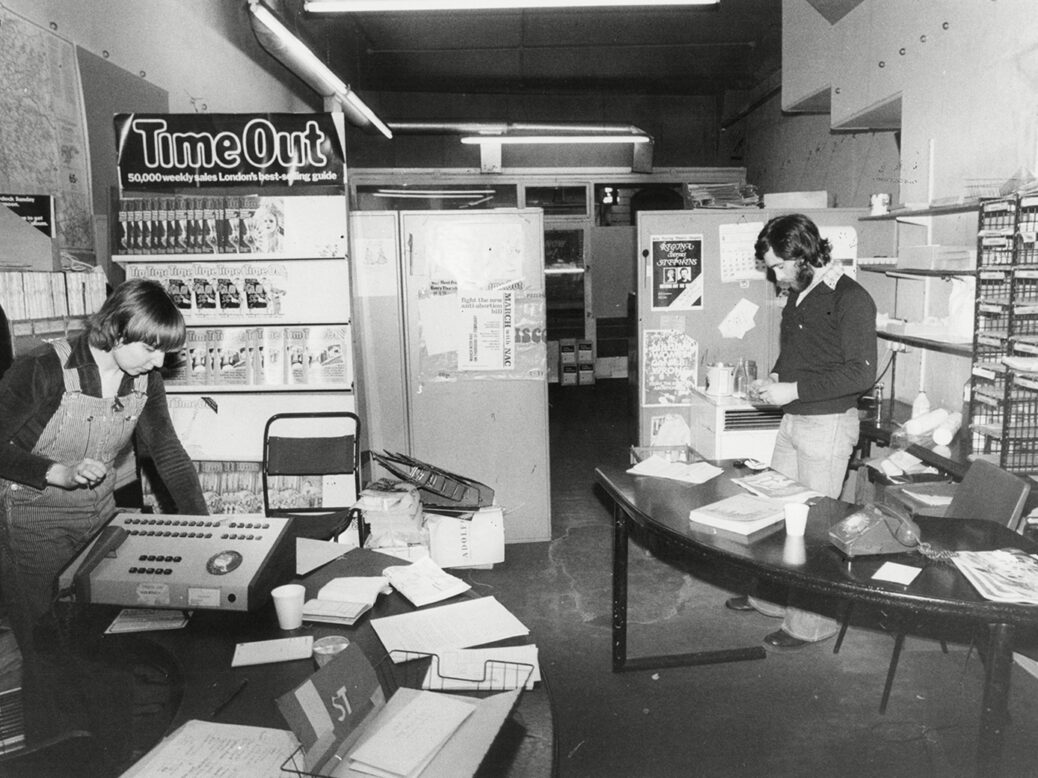

The staff had long ago outgrown the space. The office was bursting at the seams, with desks shoved into odd corners, corridors and under stairs. They were all littered with books, flyers, invitations to events and packages which it was my job to open, scrutinise and, if important, distribute to the relevant editors (one or two Mac lipsticks were, if I’m honest, distributed directly into my handbag). Everywhere there were stacks and stacks of old copies of the magazine. It was the first office I’d worked in where I noticed the smell: the musty perfume of newsprint clung to my clothes and hair long after I left work in the evening.

The magazine’s clubs editor, Dave Swindells, also a notable nightlife photographer, took me under his wing. I was sent to review gigs and club nights, and to interview (usually over a pint) people I had hitherto only seen onstage. I felt like I was at the centre of the universe.

That office has now been redeveloped — the magazine and its neon sign moved in 2013, and is now in a glass and steel space in Drury Lane. And now Time Out London is to be redeveloped too: today (23 June) the company published the final issue of its print magazine. In April, it said it had taken the “strategic decision to move to a digital-first model”, meaning it will focus on its website, live events and branded markets. It’s a sad end to a magazine that defined London’s cultural life for more than five decades.

Time Out London was founded by Tony Elliott in August 1968, starting out as a one-page flyer about what was happening in London. By late September that year it was a booklet. Elliott, who died in 2020, was known for his uncanny ability to predict the next cultural success. During my stint at the magazine one of the editors had a cautionary tale about a previous intern, who had introduced themselves to a man in the lift. “Hello, I’m the new intern — who are you?” they asked. The man had studied them coolly. “I’m Tony f***in’ Elliott,” he replied. The rest of the four-storey journey was taken in silence.

The magazine has transformed since my time there. Its April 2006 bumper issue, in which I had my first byline (“The Food & Drink 50 — our essential chart of the capital’s best restaurants and bars”), ran to 194 pages. At the time its circulation was 92,233, according to ABC. By early 2012 that circulation had dwindled to 52,198, but in October that year it became a freesheet, pushing its readership up to more than 305,000, where it hovered until the first lockdown, when it went digital-only and rebranded itself “Time In”. When the magazine returned to the capital’s streets in August 2020 the damage had been done. London had changed and, as successive lockdowns were imposed, the restaurants and venues it covered had been devastated, while the commuters on which its new model depended were still staying at home.

A report published by the London Assembly’s Economy Committee in December showed the extent of the harm done to London’s night-time economy, which before the pandemic contributed as much as £26bn to the UK economy. Covid, it estimated, caused 393,000 jobs to be lost in the sector, and even after nightclubs reopened, sales were slow. James Lindsay, chief executive of the Royal Vauxhall Tavern, told the committee ticket sales were down 20 per cent, while Mark Davyd, chief executive of the London Venue Music Trust, said pre-booked tickets were down 35 per cent.

The pandemic is not entirely to blame. Decades of rent rises, changes to licensing rules and displacement by infrastructure projects (Crossrail alone closed G-A-Y, London Metro, the Astoria and Mean Fiddler) meant the number of nightclubs in the capital had already shrunk by 50 per cent between 2012 and 2017, according to the mayor’s office.

By the time I started my internship at Time Out I had lived in London for two years. It was through its pages that I had learnt about how London fit together, figuring out ways to get from a gig at Turnmills to a club night at the End or Mean Fiddler. But those venues don’t exist any more, and London’s cultural sector is struggling to keep its head above water. The demise of Time Out’s print edition should be taken as the capital’s final cry for help.

This article originally stated that ABC began collecting data on Time Out earlier than the year 2000 – and has been amended to show it didn’t.

[See also: The Death of Consensus by Phil Tinline review: the nightmares of British politics]