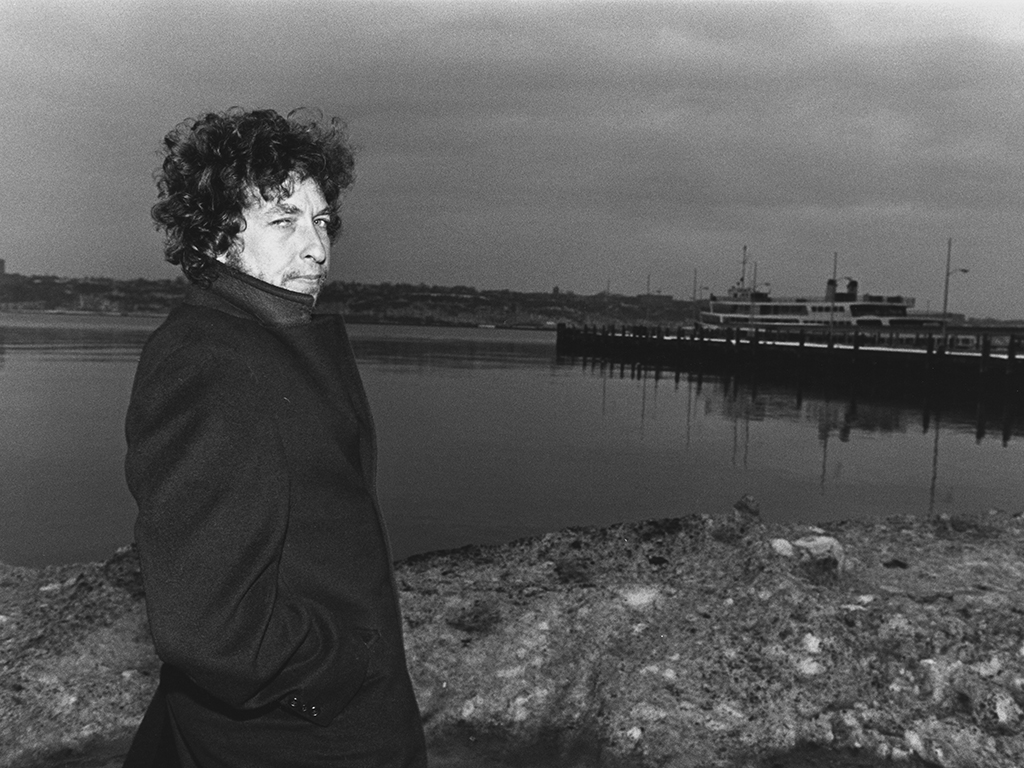

New Statesman contributors reflect on the many facets of Bob Dylan’s character and career.

His world is mysterious – he says everything and nothing at once

Yo Zushi

Songwriters like Leonard Cohen articulately present their subjective world-view, but Dylan gives us whole worlds to explore.

At 80, Dylan’s braggadocio is hilarious and heroic

Suzanne Moore

I can’t do this really. I don’t know enough about Dylan. But then who does?

Dylan’s shift from acoustic to electric in 1965 is sometimes described as his Damascene moment. In fact, it was really a development of his art.

There is dark, sly laughter behind his most puzzling lyrics

Colm Tóibín

You would need to be an awful nitwit to let yourself be irritated by Dylan’s attempts to sound deep.

Even in love songs, Dylan’s polemical streak shines through

Stephen Bush

The court may not have convicted William Zantzinger, who “killed poor Hattie Carroll, with a cane that he twirled around his diamond ring finger”, but in his ballad Dylan certainly does.

Perfect voices don’t survive the years. Dylan’s imperfections adapt

Bryan Appleyard

The point about Dylan’s voice is that it is his voice and that his lyrics are written for that voice.

His freedom spoke to me as a young almost-musician

Emma-Lee Moss

No, I wasn’t picking up my life after a doomed marriage and heading down Highway 61. But I was out of school, and had valid ID, a MySpace profile and a pay-to-play slot at the Camden Barfly.

Dylan’s paintings are of a piece with the folk roots of his music

Michael Prodger

Dylan’s main subject in his artwork is quotidian America, light on people and redolent with atmosphere – ennui, melancholy and alienation.

This article appears in the 19 May 2021 issue of the New Statesman, In defence of meritocracy