The portraitist Sir Joshua Reynolds, founding president of the Royal Academy (RA) and painter to George III, was a copper-bottomed grandee. He taught the students of the RA that copying from the antique and the best examples of Italian Renaissance art was the best method to improve both themselves and the British school of art more generally. In this piece from 1923, on the 200th anniversary of Reynolds’s birth, John Alton looked at how far the artist’s reputation had fallen. The attacks on the great man had been many and concerted over the years, from Ruskin to Roger Fry, and, said Alton, Reynolds deserved better. For all Reynolds’s weaknesses, “There is a flavour, a suitability in his work that gives it an association value that will last as long as the houses it was made to adorn,” and Alton was convinced that his reputation would one day rise again.

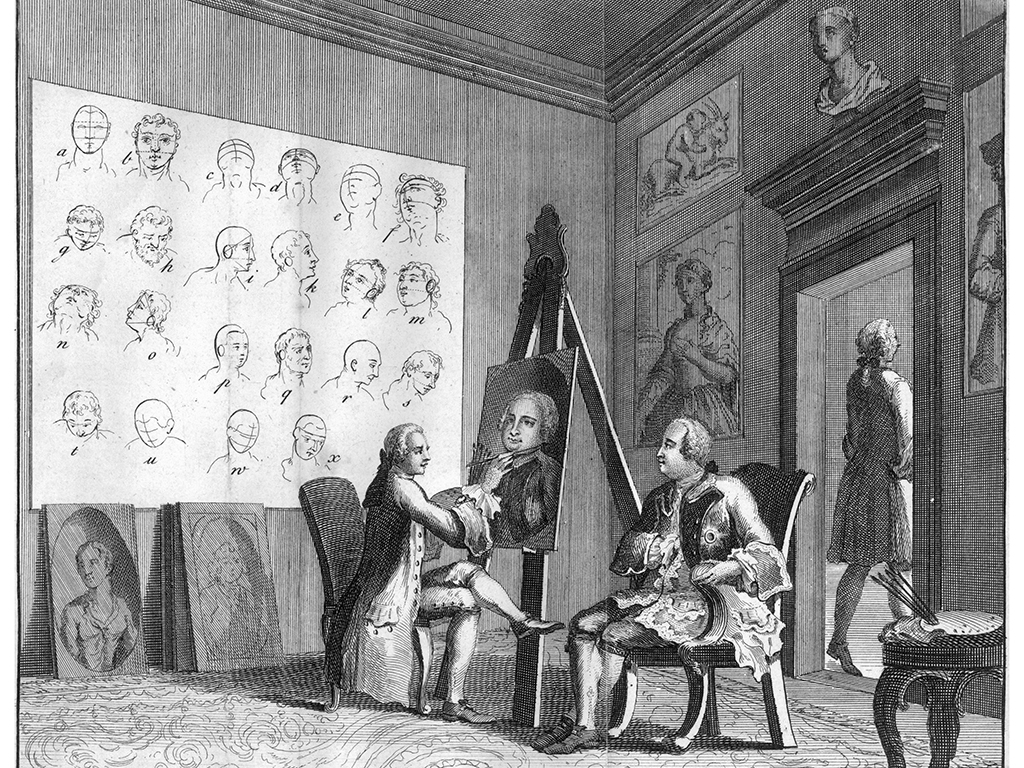

The Royal Academy has recently celebrated the centenary of Sir Joshua Reynolds. Two hundred years ago the first president of that institution was born. It came into being under the royal sanction of King George the Third in 1768, an event, says Sir Joshua, “in the highest degree interesting, not only to artists, but to the whole of the nation”. As a stimulus to the celebration the authorities have exhibited some relics and a few pictures; among them portraits of George the Third and Queen Caroline, a portrait of the artist and of his assistant Giuseppe Marchi.

There is something pathetic about these decaying mementos; the blackened and cracking portraits, the sedate mirror-form palettes set with chemically unsound colours, the engagement diaries, kept like a dentist’s appointment book, the little blue silk coat and the chair – the sitters’ chair, of which the inscription runs: “This chair was occupied in turns by the most illustrious Statesmen and Warriors, by the most eminent Lawyers, Poets, Philosophers, Actors and Wits of the eighteenth century. The loveliest and most intellectual women of that time have sat in it. The majestic Siddons leaned her arms upon it as the tragic Muse, Kitty Fisher lounged in it as Cleopatra.” Thus are we helped to recapture the spirit of that lush and liberal age.

The atmosphere of the Royal Academy summer exhibitions has perhaps assisted in tarnishing Sir Joshua’s memory. From the painter of today he receives too much blame, for he bears the stigma of responsibility for the hopelessness of the academic outlook. This is unjust. His aims were far higher, and to comprehend them properly we must study not his works alone, but also his criticism. To those who have had the advantage of hearing the judgement of the critics of the 19th and 20th centuries upon his pictures, a first reading of The Discourses comes as a surprise. Ruskin, one of the earliest counsels for the prosecution, remarks on the difference between Reynolds’ practice and his precept. Cunningham also mentions this in his Life of Sir Joshua Reynolds, and cruelly suggests that his precepts brought about the financial ruin of James Barry, while his own neglect of them put him “in a coach with gilded wheels and the seasons painted on its panels”. We can forgive the injustice of the phrase for the sake of its rich suggestion of the age.

[see also: John Ruskin: a prophet for our troubled times]

Later, Mr Roger Fry says that we “are forced to the conclusion that Reynolds was ahead of his generation in critical acumen”. It is only fair to Mr Fry to say that he adds a remark to the effect that Reynolds suppressed these advanced inclinations in practice. As a critic Reynolds is undoubtedly a great man. As a painter he has been sufficiently crabbed to satisfy the malignity of the most eager iconoclast, though usually with some justification. When we think how unlikely it is that we should ever meet a man who should say, “I have just seen a stunning drawing by Sir Joshua Reynolds,” we may form some estimate of the improbability of his rousing great enthusiasm in our age, which demands drawing and holds it in such high esteem. But whatever we may think, his contemporaries had certainly no doubts about him, and to appreciate his work to the full we must first put ourselves back in his age and try to see what it was he attempted to achieve.

When we consider the position of art in England in the early 18th century we find considerable food for reflection in the fact that Reynolds and his contemporaries attempted to give it social prestige. It is from him that our artist knights descend. Yet we must not think of him as a place-seeker; his intention was to bestow dignity upon the profession and there is no doubt that he did so. He left so deep a mark upon his age that we still speak of the Reynolds period. There is a flavour, a suitability in his work that gives it an association value that will last as long as the houses it was made to adorn. As an artist this is his greatest achievement.

Yet it was largely owing to his own efforts that those further discoveries in art were made in England which eventually resulted in his own discrediting. He himself was responsible for the turning of men’s attention to the beauties of Italian painting, from which Ruskin drew the knowledge which enabled him to reduce Sir Joshua’s reputation. Had Ruskin not been such a moralist he would probably have been able to make himself more clear, but we do catch a suspicion of his meaning when he says, speaking of the portraits, “Sir Joshua’s pretty lady is there for herself alone, feeling nothing in particular, arriving at nothing in particular; not a saint, not a heroine. The Hon. delightful and beautiful Mrs So-and-So. That is all.” On the surface this comment seems rather complimentary, but Ruskin undoubtedly wishes to say that the picture conveys no more than a photograph does.

[see also: Raphael, the painter of perfection]

He is nearer the point when he says that Reynolds “never suspected that there was a spirit in Michelangelo that he had not”; and while looking at the Burlington House painting of a woman with a scroll seated on rolling clouds, we are led to suspect that Reynolds sought only for the worst in Michelangelo and found it good. Mr Fry suggests that Reynolds was fully conscious of his failure, and a remark in the Discourses, that “sometimes a painter by seeking for attitudes too much becomes cold and insipid” bears this out.

After Ruskin, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, an astute critic, and one familiar with the best Italian art, sums up in a mot his contemptuous opinion: “Sir Sloshua” he calls him. Malicious but expressive. Since then the attack has been regular and deadly.

In the early part of this century Mr Fry, in a preface to the Discourses, writes what we might almost call a defence of Sir Joshua, which is certainly one of the best and fairest critiques on his works. “Reynolds,” he says, “found by his own failures in poetical composition that he had not the particular gift of invention, without which such work falls into turgid rhetoric… he probably never concealed from himself his real failure.” This is criticism, clear and credible, unlike the moralising of Ruskin but no less deadly.

[see also: The rural fantasies of Helen Allingham]

At the present time the reputation of Reynolds has fallen so low that we may expect a reaction. It cannot be that the present estimate is the final word. There is a quality of greatness in his work which cannot be denied. Gainsborough is a lovely painter and an undoubted genius and yet there is manifest in Reynolds’s best portraits intended greatness which Gainsborough never achieved. Momentarily this is a heresy, but heresies have often seemed reasonable to the next generation. Reynolds represents something which no other artist does; in spite of our dislikes we are obliged to admit his dignity, and the importance of his position in the English school of portrait painters cannot be overlooked. His decline in favour is really due to a false inflation; when the effects of that are past, we shall regard him justly.

Read more from the NS archive here, and sign up to the weekly “From the archive” newsletter here. A selection of pieces spanning the New Statesman’s history has recently been published as “Statesmanship” (Weidenfeld & Nicolson).