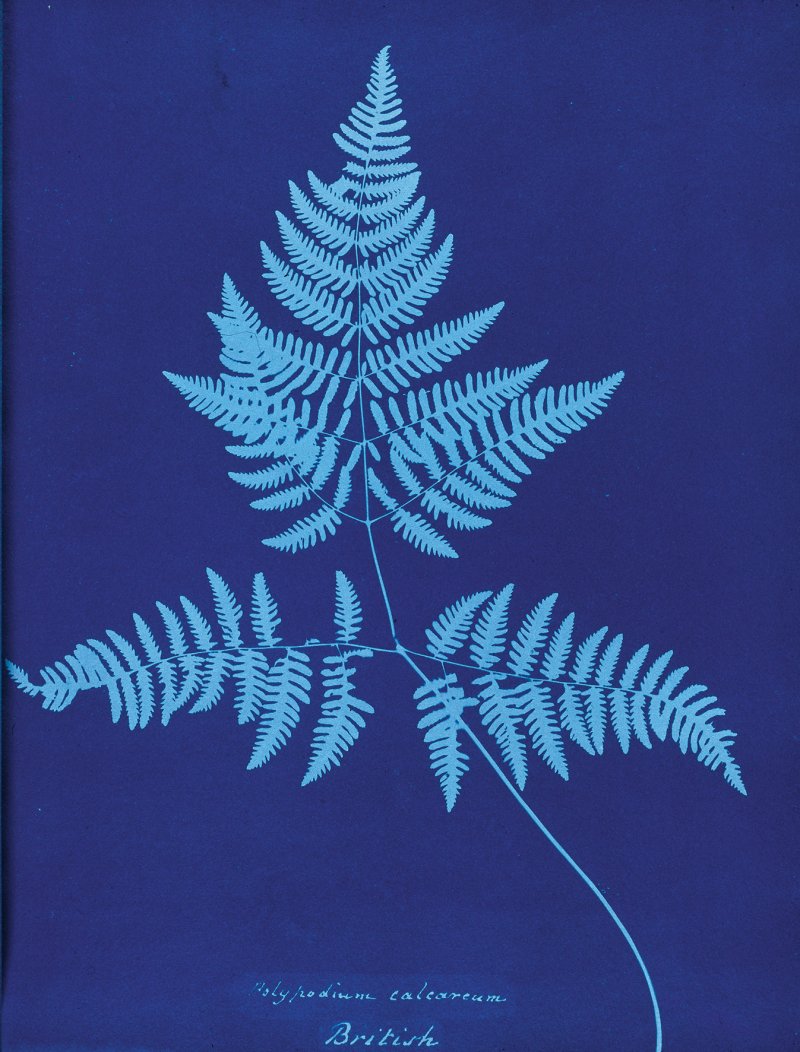

In the late 1880s, a bibliophile and photographic historian named William Lang came across some intriguing photographic prints of algae. They showed the specimens as white silhouettes against a Prussian blue background and he recognised them as early examples of the cyanotype process. Cyanotypes are cameraless photographs, made when an object – a botanical specimen, a feather, a bit of lace or some such – is placed under glass on chemically treated paper and left in the sun. When the object is removed and the sheet washed down, a ghost shadow remains where the light hasn’t reached the paper. The process, later adopted by architects to reproduce their drawings, is where the term “blueprint” comes from.

The prints Lang found were collected in a roughly bound book called British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. No author name was given, just, hidden away, the initials “AA”. Lang assumed they stood for “Anonymous Amateur” but in fact they stood for Anna Atkins.

What Lang held in his hands was an extraordinary conception; a work made between 1843 and 1854 with a projected three volumes containing 398 plates and 14 pages of text, all cyanotype reproductions. British Algae is the first book produced entirely using photography. The work was never a commercial venture – Atkins circulated the volumes to her “botanical friends”, periodically sending new images for them to stitch into the books – and it is not known how many copies she actually made, but there are around 15, of different stages of completion, known to survive.

It is no surprise then that Lang recognised the process but not the prints’ maker, and despite her contributions to botany and photography Atkins remains a fugitive figure. Like her peers the palaeontologist Mary Anning and the mathematician and astronomer Mary Somerville, Atkins (1799-1871) was a pioneer at a time when the natural sciences had little use for women. Atkins’s interests were very much of her era and her cyanotypes can be seen as part of the pteridomania – fern fever – that permeated Victorian Britain and found expression in everything from dresses to tea sets and fire grates. Atkins’s photographs, however, transcend mere biological cataloguing and reveal in their careful and harmonious compositions her original desire to be an artist.

[See also: The blossom-filled landscapes of Charles Conder]

Although botany was regarded as the most ladylike of the natural sciences – indeed, the Botanical Society in London was the first of the major scientific societies to admit women (Atkins was elected in 1839) – it was status and family connections that really allowed her to follow her instincts. Her father, John George Children, was an eminent chemist, zoologist and mineralogist who was a fellow of the Royal Society and became keeper of the Department of Natural History and Modern Curiosities at the British Museum. Atkins formed a close collaborative bond with her father after her mother had died from the effects of childbirth.

In the early 1820s she made 256 detailed drawings to illustrate his translation of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s Genera of Shells, published in 1823, and she also accompanied him on a trip to the battlefield of Waterloo in 1818, where she drew the celebrated “Waterloo elm”, a tree that marked Wellington’s command post during the fighting. When Children learned that the elm was to be felled he bought it off the local farmer, had it transported to England and commissioned Thomas Chippendale’s son to make a chair from the wood, which he then presented to the Prince Regent. In her memoir of her father Anna recorded that he had another chair made for her, but he gave it to the Duke of Wellington instead.

It was Children who introduced Anna to his scientific friends, among them the polymath Sir John Herschel and the pioneering photographer Henry Fox Talbot. It was from Hershel, the man who invented cyanotype, that she learned the technique, while her marriage in 1825 to a wealthy West India merchant, John Pelly Atkins, meant she had the leisure and funds (the couple had no children) to make botany and photography more than hobbies. Atkins is known to have owned a camera but no photographs survive, and so the claim that she was the first female photographer cannot be verified.

[See also: The ruin-strewn landscapes of Hubert Robert]

Many of the seaweed specimens used for her cyanotypes came from her own extensive collection. She made the prints with the help of her household staff and with an old childhood friend, Anna Dixon, who was “like a sister” to her and was also a distant cousin of Jane Austen. In her introduction to British Algae, Atkins explained that she had initially intended to draw the images but, “The difficulty of making accurate drawings of objects so minute as many of the Algae and Conferva, has induced me to avail my self of Sir John Herschel’s beautiful process of Cyanotype, to obtain impressions of the plants themselves, which I have much pleasure in offering to my botanical friends.”

Atkins produced two other books with Dixon and over the course of her career made more than 6,000 cyanotype prints, each one on 8 x 10-inch sheets of hand-treated paper, although the later assertion that she was also the author of five novels, including The Perils of Fashion and Murder Will Out, is false. However, if her indefatigability is not in doubt, nor is her eye. She arranged her specimens with all the care the Pre-Raphaelite painters were then using in their own minutely observed painted depictions of foliage, filling her sheets with delicate tracery and adding samples or bending plants to give the most satisfying arrangements. In some, every nodule is clear, in others her plants are evanescent and floating, barely seeming to touch the paper. Ruskin’s injunction extolling “truth to nature” while “rejecting nothing, selecting nothing and scorning nothing” did not just inspire mid-19th-century painters but Atkins as well.

Atkins died at the age of 72, brought down by “paralysis, rheumatism, and exhaustion”. She had made no effort to ensure her renown and was quickly overlooked. Her cyanotypes, however, are a record of a woman who never tired of examining nature, and for all their botanical accuracy her tiny worlds in which plants take on the forms of river deltas and etched patterns are simply images of extraordinary beauty too.

[See also: The endless vistas of Joachim Patinir]

This article appears in the 21 Apr 2021 issue of the New Statesman, The unlikely radical