One of the great surprises of last June’s general election was the total vote of the two main parties. For the first time since 1970, both won more than 40 per cent of the vote. The polls did not predict this; but the surprise went deeper. It was commonplace to observe that both parties had deserted the centre ground – the ideological territory where most voters think they live and where elections are traditionally won and lost. If neither party reflected the outlook of most voters, how come both won so much support?

A large part of the answer comes from a special YouGov survey conducted exclusively for the New Statesman. It shows that ideology, as defined by political theorists and commentators, is very different from ideology as viewed by millions of voters. The former is tidy, the latter messy. Theorists detect a coherent intellectual structure to the concepts of Right and Left; voters hold a variety of pick-and-mix attitudes to the issues of the day.

However, what does emerge is that on most issues (though not all), Jeremy Corbyn’s view of society is more in tune with the British people than the centreground theory of electoral success would predict.

To create an ideological map of today’s Britain, YouGov questioned voters on 17 fundamental values. In each case, it offered a pair of statements, and asked respondents which of the two statements came closer to their own views. In each case, one statement was broadly “left” and/or progressive, the other “right” and/or traditional. The survey explored views ranging from economic beliefs (capitalism, public services, tax-and-spend, equality etc) to social values, such as welfare, gender pay gaps, immigration, Muslims and gay rights.

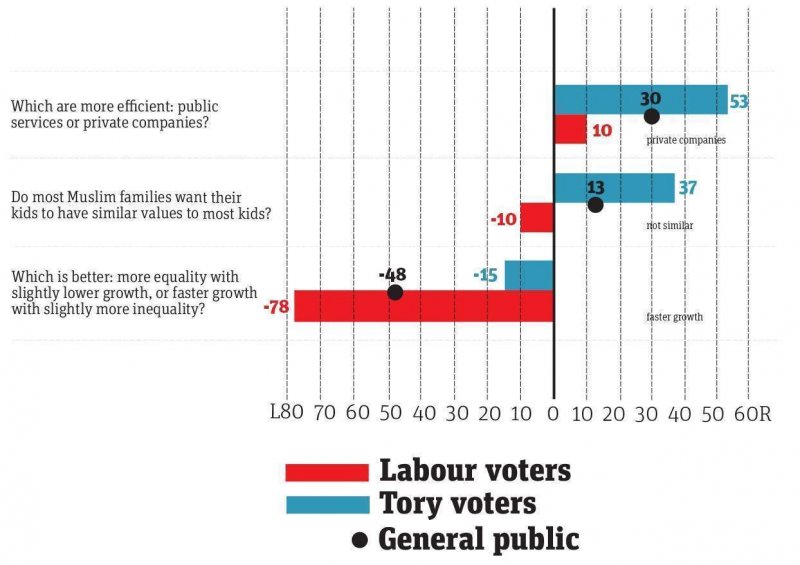

A glimpse into the variety of public attitudes comes in their views of the capitalist system. Even Tory voters think large companies make excessive profits – while even Labour voters tend to regard private companies as more efficient than the public sector.

However, it’s also worth noting that Labour voters, on balance, veer to the right on just two of the 17 issues we tested: free trade and the efficiency of the public sector. Conservative voters, on the other hand, veer to the Left on as many as six issues: regulation, diplomacy vs military strength, corporate profits, tax-and-spend, equality, and gay rights.

Overall, the public is on balance, on the right on just three issues, fairly evenly divided on four, and on the left on as many as ten. And it is not only that Labour voters are more Corbynite than Blairite. On some key ideological tests, of which nationalising the utilities is just one, so are the British public, including many Conservatives.

That said, the full ideological map presents a more complex picture. One clear finding is that some of the debates of yesteryear have gone away. One of the great causes of the left used to be opposition to free trade and globalisation. This lay behind its opposition to UK membership of Europe’s common market. On the other side of the divide, Margaret Thatcher’s free market right wanted to free British companies from the burden of excessive regulation.

Yet today, only 20 per cent of Labour voters oppose free trade, while just one in three Tories believe that “government regulation of business does more harm than good”.

Even the enduring arguments about state-vs-private ownership of industry are no longer as simple as they seemed to be. On the one hand, the public tends to prefer state-run to privately-run utilities. By 67 per cent to 19 per cent we reckon that “business corporations make too much profit”. Based on this figure alone, it might be possible to conclude that Britain’s electorate is clamouring for full-blooded socialism.

But wait. By 54 per cent to 24 per cent, we also think that big companies in the private sector tend to be run more efficiently. And the electorate divides evenly on the merits of private sector competition. Roughly a third say that more competition increases living standards for most people. Yet another 38 per cent, though, reckon that private sector competition “reduces the living standards of millions of people” and mainly helps the rich.

It is not, however, that traditional left-right conflict which divides Labour voters most from Conservatives. The biggest single difference concerns welfare. By a margin of 47 points (66 per cent to19 per cent) Labour voters want the government to “do more to help needy British people, even if it means going deeper into debt”. Yet by a margin of 46 points (68 per cent to 22 per cent), Conservative voters plump for the opposite view. They believe that “the government today can’t afford to do much more to help the needy”. Taken together, those 47 and 46 point margins generate a massive 93 point gulf between Labour and Tory voters. We find almost as great a gulf, 91 points, when the voters are asked whether poor people “have it easy”, or “lead hard lives”.

A third big gulf between Labour and Tory voters concerns the trade-off between equality and growth. This time, though, it’s not that the two sets of voters stand on either side of the fence. In fact, Conservatives think equality matters more than growth, by 54 per cent to 39 per cent. The party difference arises because of the overwhelming response of Labour voters, who divide by a crushing 84 per cent to 6 per cent in favour of greater equality over faster growth.

The two other seriously big divides concern race and immigration. Most Labour voters think black Britons are held back by discrimination, and also that immigrants are more of a strength than a burden to Britain today. But in both cases, one in four Labour voters take the opposite view. Most Conservatives reject the discrimination and strength arguments – though, again, a minority disagrees. There is also a party divide, though not quite as large, on the pay gap between men and women. By more than two-to-one, Labour voters blame discrimination, while Tories are as likely to think that the main reason for the pay gap is that women make different choices about their lives and careers.

There are two issues on which at least six out of ten Labour and Tory voters agree. One concerns homosexuality. The great battles of the second half of the 20th century are now over. A large majority of Tories, as well as an overwhelming majority of Labour voters, reject the view that it should be discouraged.

The other near-consensus is, perhaps, more surprising. If forced to choose between higher government spending and lower taxes, Labour voters opt for more spending by 78 per cent to 8 per cent “even if this means higher taxes for people like me”. But so, too, do 63 per cent of Conservatives. Only 26 per cent opt for the lower tax option.

Before anyone in Corbyn’s office opens a bottle of organic fizz to celebrate these results, a word of caution. Values and ideology shape a voter’s outlook, but they are not the only things that matter. Competence and leadership are as important, sometimes more so. Voters may like what a party stands for, but they must also believe it will run the country effectively and actually deliver what it promises.

This is why left-wing cheer over these findings should be tempered. Other recent YouGov surveys show that Theresa May is still preferred as Prime Minister, albeit by far less than a year ago. Labour is behind the Tories on the economy, and only level-pegging on taxation. Corbyn’s Labour Party has yet to achieve a clear lead on voting intention. The results of this latest survey, showing the popularity of left-wing Labour values, also serve to emphasis the gap between values and votes. If the challenge for May is to align her party with the people’s values, the challenge for Corbyn is to win over the millions of people who like what he stands for but are still not convinced of the case for voting for him.

Peter Kellner is the former president of YouGov; the full results can be viewed at www.yougov.com