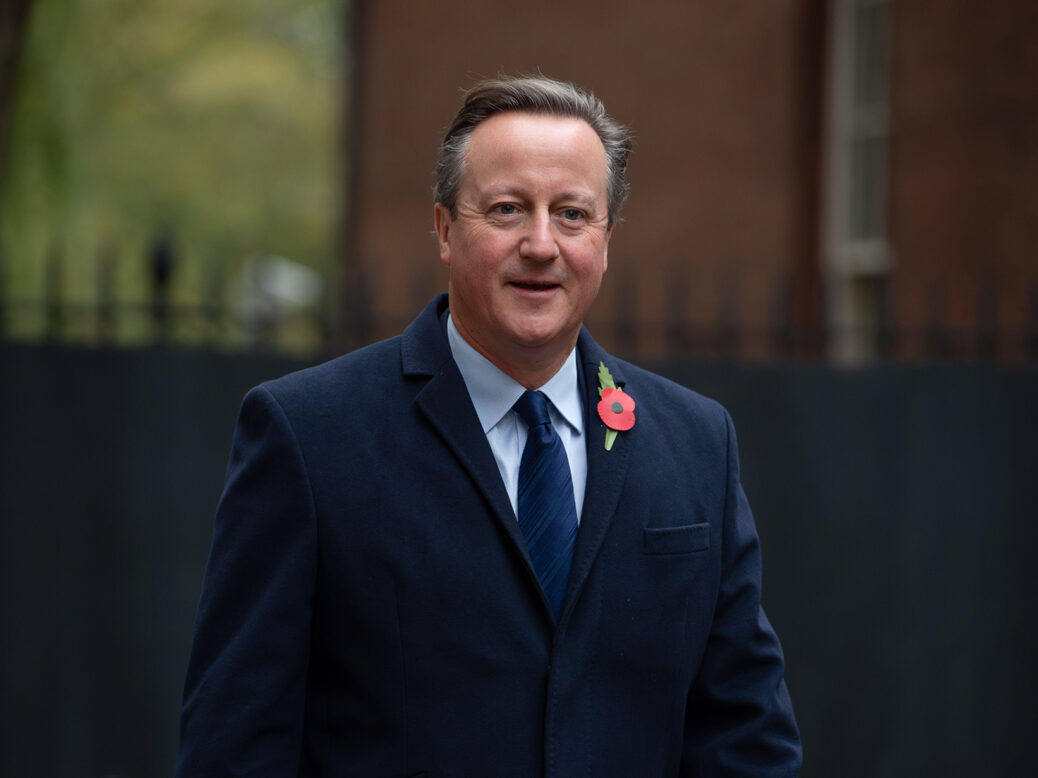

The first thing to say about the newly ennobled Foreign Secretary David Cameron is he is not in any way popular. In 2018, when the recovering prime minister first told “friends” he’d be interested in the role, YouGov found that a majority of the public opposed the idea, and less than a quarter were in favour. Given that Cameron’s role in the Brexit referendum had been perfectly pitched to alienate both sides in the febrile political atmosphere of that year, I’m surprised support was that high.

That was five years ago, of course, but the same pollster’s tracking of assorted politicians’ reputations shows that things have not improved since. Cameron has lower net popularity than every living ex-prime minister except Liz Truss. (The lettuce, one suspects, would also poll better than Liz Truss.) Even post-partygate, Boris Johnson not only has more partisans, but also, damningly, fewer haters. The idea Lord Cameron is popular is demonstrably untrue.

The second thing to say about David Cameron, however, is that there are extremely good reasons for this. The United Kingdom is a weaker, grubbier and more divided country than the one he inherited in 2010, and this is to a significant extent his own fault. In a very real sense, we are all suffering from Long Cameron.

That those of a certain liberal, centrist milieu might look back fondly on the Cameron years as a golden age of cooperation and stability is hardly surprising. The coalition showed he could work across party lines, and made a big thing about being polite, even complimentary, about his opponents. As with the harking back to the 2012 Olympic opening ceremony you find in certain corners of the internet, nostalgia for Cameron is nostalgia for an era of apparent chumminess, cooperation and stability – a lost golden age, before everything was ruined by Brexit and Johnson and Truss.

It was also, however, the age in which the foundations were laid for everything that has gone wrong since. The original sin, of course, was austerity: a catastrophic, ideological misreading of the workings of the public finances, and the role the state plays in growth, which was already well under way when those nurses were dancing around Stratford in 2012. That British politics is still accompanied by a drumbeat of stories about councils falling over and public services struggling to recruit in 2023 can be traced directly to the cuts Cameron backed in 2010: not because they were necessary, but because he thought they were right.

Those cuts did not just choke off the nascent post-crash recovery that Labour left behind: Cameron Conservatives also sent Britain hurtling out of the European Union. Researchers have found that exposure to welfare cuts led to an increased propensity to support Ukip so strong that, without them, Britain would almost certainly have voted Remain. That same 2014 spike in support for Ukip, of course, was what led David Cameron to promise a referendum in the first place, to settle an argument he claimed was tearing the country apart. He was not the last leader to conflate party with country and thus set the latter on fire. But nonetheless: the Brexit vote, and all that followed, can be traced directly to the failure of his political strategy, in which he offered an angry country a generational change in foreign policy he had not planned for and didn’t even support. This man is now Foreign Secretary.

That 2016 vote, of course, also set the country against itself in a way that was entirely predictable, if only because it was exactly what had happened when Cameron had offered a different referendum to Scotland less than two years earlier. It coarsened our politics, by providing some of the nastiest and least principled politicians and journalists in the country with a populist cause and a way of delegitimising their opponents. It provided Boris Johnson with his long-awaited route to Downing Street. And like austerity before it, it weakened the economy meaning that wages have continued to flatline and relative living standards to decline.

All this Cameron did without eliminating the deficit he claimed was the point of the exercise. Even Britain’s lack of pandemic preparedness can be traced in part to the short-termist and penny-pinching culture established under his government. He may have seemed plausible, pleasant, even statesmanlike compared to some of those who followed – but he’s nonetheless the source of so much that has since gone wrong. And he spent his time out of office lobbying ex-colleagues on behalf of his new employer, too.

We’ve heard a lot these past few years about “Long Corbyn”: a devastating post-leadership syndrome said to be afflicting a Labour Party that was struggling to regain the trust of the voters. Whether that was fair or not, the last year and more of polling suggests that Labour is well on the road to recovery. Yet the Tory party’s Long Cameron remains not just untreated, but as his return to high office suggests, undiagnosed, and is raging through the country even now. Both party, and nation, will be managing the symptoms for a very, very long time.

[See also: The Israel-Iran endgame]