On the bus from the port, the first thing Bibby Stockholm’s asylum seekers see as they leave is a tank – its muzzle trained on their blacked-out windows. Naval detritus litters the route from the diseased barge to town: anchors, cannon, a sea mine. Outside the car park lurks a torpedo, like the one that sank the Belgrano.

It’s all costume now. The old Navy base on the isle of Portland, off Dorset’s Jurassic Coast, was sold in the Nineties. A wealthy family, the Langhams, run it as a private port. They donated £70,000 to Ukip, and now they’re making a reported £2.5m off the Home Office to host 500 men on Britain’s first asylum barge, which slotted into port three weeks ago like a Tetris piece.

This commercial deal wasn’t run past the 13,400 population of Portland. “They’re making millions, and the town gets nothing,” said Pete Roper, an independent town councillor who was Portland mayor until May. A retired IT worker, the 68-year-old has lived here for eight years – a “kimberlin”, as outsiders are known. In a polo shirt and shorts, he’s just about cultivating the Channel-whipped walnut hue of a local.

The town council is Labour-dominated bar five independents. It hires security guards for public meetings now. Roper has received intimidating calls; county councillors are confronted in supermarkets. Letters warned local businesses not to service the barge – someone with a copy told me it was signed “Britain First” (the far-right group denied responsibility).

Some welcomed the first arrivals with care packages of deodorant, notebooks and flowers and condemned the barge, which the Fire Brigades Union deemed a “potential deathtrap” (designed for 222, it now has bunk beds for 506). Others begrudged its gym, medical care and free meals. “They’re living like kings,” a protester said at the port gates. Days later, the Home Office began temporarily removing people from the barge after traces of Legionella bacteria were found in its water system.

I met Ali*, 25, and Omar*, 20, in Weymouth, a bucket-and-crab coastal town on the mainland where crowds watched Punch and Judy and queued for the helter-skelter. They had wandered along the beach, called their sisters, but couldn’t do much else. Banned from working, they receive £9.50 a week – not enough to waste on trying battered cod or buying an ice cream (a 99 here goes for £2.50). On their second night on the barge, they watched Marvel’s Thor: Love and Thunder and ate chicken with corn and olives, cooked by Arabic chefs whom they praised.

In plain T-shirts, trainers and dark trousers too hot for a seaside scorcher, they were neatly shaven (“we can also do the big beards!”) and squinting against the sun. They arrived from Pakistan by plane six months ago and claimed asylum at the airport. Since then, they’ve been housed in Eastbourne and Bournemouth hotels. When Omar – who felt settled in Bournemouth – refused to leave, the government said he had “no choice”.

As members of the minority Ahmadiyya sect, they were escaping Pakistan’s blasphemy laws. Ali had been jailed after three years as a police constable because of his faith, and left without food or a change of clothes for days. Omar had his computer science degree cut short. They chose Britain, home to Ali’s first cousins and the Ahmadiyya headquarters.

[See also: What politicians don’t understand about asylum seekers]

“Allow us to work, we want to pay taxes, help the economy,” said Ali. “We are doing nothing, and you’re paying for everything.”

“The barge is difficult to live on – there’s no engine, no escape: you look out of the window and it’s just water. It feels dangerous and old. The rooms are very small, it’s kind of like a prison,” said Omar. “But we are not illegal.” He returned that evening to infected drinking water.

When they were on the barge, they were told they might be stuck there for nine months. Now, they await their return. I hear other barge residents have come from Yemen, Iran and Sudan. Portlanders nickname them “bargemen”.

Like a loose fang, Portland dangles off the mainland from a solitary road, buffered by a shaft of shingle along Chesil Beach. Its surface etched by quarries, the isle’s stone was used to lend puddle-grey stoicism to better-loved bits of Britain: Buckingham Palace, the Cenotaph, St Paul’s. Victorian convicts built their own prison with it here. There are two: a young offenders’ institution and the Verne, for sex offenders (“Paedo Alcatraz” in tabloidese), where Gary Glitter was recently recalled.

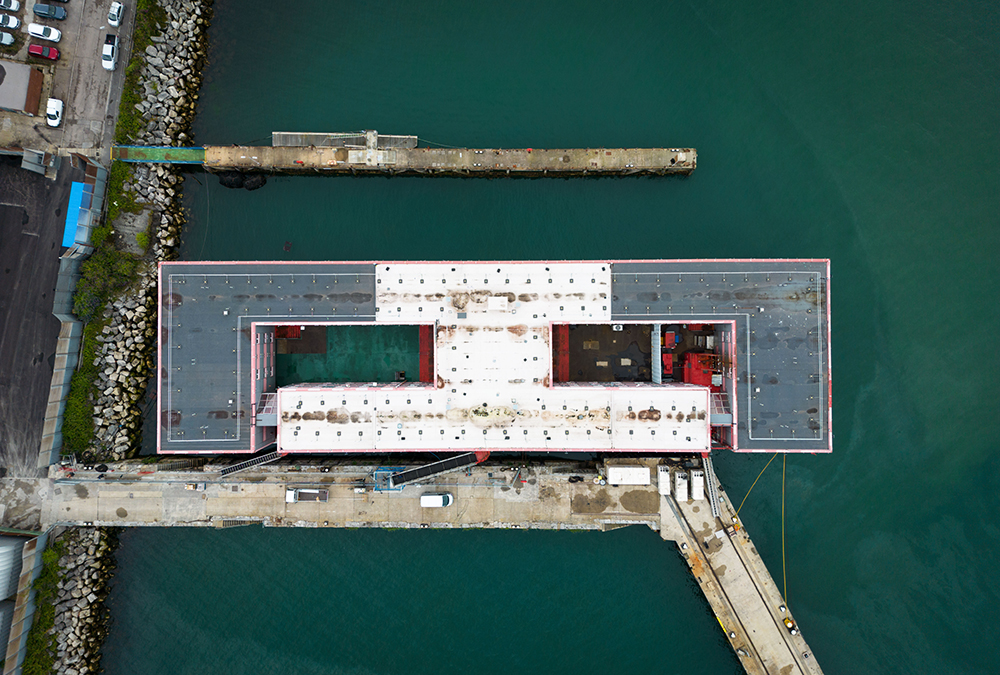

The penal citadel is at the top of Portland, where yelps of seagulls give way to snickering crows. You can see Bibby Stockholm clearly from the Jailhouse Café garden. Cameramen chain-drink mugs of tea and zoom in on nothing. Just 39 men boarded this week, and have since been disembarked. Lawyers helped 20 at a Bournemouth hotel stay put.

An oblong clad in municipal leisure-centre grey and pink, Bibby Stockholm looked Lego-like among its peers – the Sir Tristram, a svelte special forces training ship that in its wilder days whooshed to the Falklands, and the towering RFA Mounts Bay almost upright in salute.

Called a “floatel” when built in 1976, Bibby Stockholm has housed Hamburg’s homeless and rig-workers in Scotland. An Algerian died onboard in 2008, when asylum seekers were detained there in Rotterdam. His heart failed. It has drawn comparisons with HMP Weare, a brutalist prison boat that docked at the same spot in March 1997 – the last time our public services ran out of everything but bad ideas.

Portland has some of England’s most deprived neighbourhoods. In the last five years the hospital lost its beds and minor injuries unit. Low-wage jobs compel the young to leave.

“To people hostile to the refugees,” said Philip Marfleet, a 75-year-old professor from nearby Poole, “we say focus your efforts on the government, which is responsible for running down the local economy, and 30 years of disinterest in the lives of local people.” Marfleet is a member of Stand Up to Racism Dorset and has researched Portland’s decline.

Volunteers plan walking tours and cricket matches for the newcomers, and an extra £2m was granted to help Dorset Council step up provision. But I watched two Bibby buses arrive in Weymouth while two local services were cancelled back-to-back, leaving a queue of sweltering pensioners waiting an hour at the same bus stop. A taxi driver told me that if asylum seekers miss the bus, they can call a number that goes through to local firms. “They’re getting everything for free and this is one of the poorest places in the country,” he said. “Drunk idiots might kick off; I told my Indian friend to be careful, in case he’s mistaken for a bargeman.”

A Dorset Police source told me, “People weren’t consulted and they’re concerned and angry – we’re just trying to keep the peace.”

Vaping on a slipway as sails rattled in the breeze, Bob*, 52, served in the Merchant Navy for three decades. He first visited Portland on shore leave in 1991, and knew the ways of big groups of men with little to do. He repeated a trope all over online groups accusing Muslims of disrespecting women, but noted they were unlikely to drink. He had a “horrible feeling that if something happens, it will be caused by a Brit. The community can self-destruct on its own; this is just ammunition.”

Like others, he questioned whether people due aboard are refugees. “They should be stopping in the first safe country they reach, like France,” he said. “They’re shopping around.” He was echoing Lee Anderson, the Conservative Party’s deputy chair and in-house irate Facebook uncle who suggested they “f**k off back to France” and stop following a “shopping list” of destinations. The Justice Secretary Alex Chalk steadily suggested this “salty” language spoke for the country. No 10 did too.

Just 15 per cent of those applying for asylum in the UK are refused. But there is a huge backlog, and the government now spends £6m a day housing 50,546 asylum seekers in hotels while they wait. These are politically toxic – attracting riots and roadblocks. Bibby Stockholm is the first of three barges the government has commandeered to use instead.

Having visited with fellow councillors, Roper said it was “appalling” and “bordering on inhumane”, recalling low ceilings, cramped corridors and deafening acoustics. One ex-port employee warned that there aren’t enough fire engines nearby to reach the barge in time if there’s a fire, and without an experienced crew it was even at risk of listing if water was pumped in. He also thought its sewage system wouldn’t cope. The Home Office didn’t address these claims.

For a place so literally named – Underhill, Tophill, Easton, Weston – Portland is quite the metaphor. A hulk of English paranoia, its creases and crags are poised for disaster. Even the word “rabbit” here is bad luck (quarrymen feared “long-eared furry things” could cause landslips). Fortifications sprung up in 1860 for fear of an imagined French invasion. A nuclear sub anchorage means the council stocks iodine tablets for everyone within a 1.5-kilometre radius.

But Portlanders are running out of things to defend. Wherever they stand on migration, they feel overlooked by the British government. The only patriotic plea I heard was from their new neighbours. “You have freedom, justice, nice people, good jobs, beautiful beaches,” smiled Omar. “I want to live my life here.”

*Names changed on request of anonymity.

[See also: Don’t assume that migrant-born politicians should be pro-immigration]

This article appears in the 16 Aug 2023 issue of the New Statesman, Russia’s War on the Future