The oil and gas giant BP posted its financial results for the past year this morning (7 February), revealing underlying profits that had doubled in 2022 to $27.7bn, from $12.8bn in 2021. The rise was driven by the war in Ukraine, which has pushed up the wholesale prices of fossil fuels. Critics such as the Institute for Public Policy Research, a progressive think tank, called the company’s profits “scandalous”.

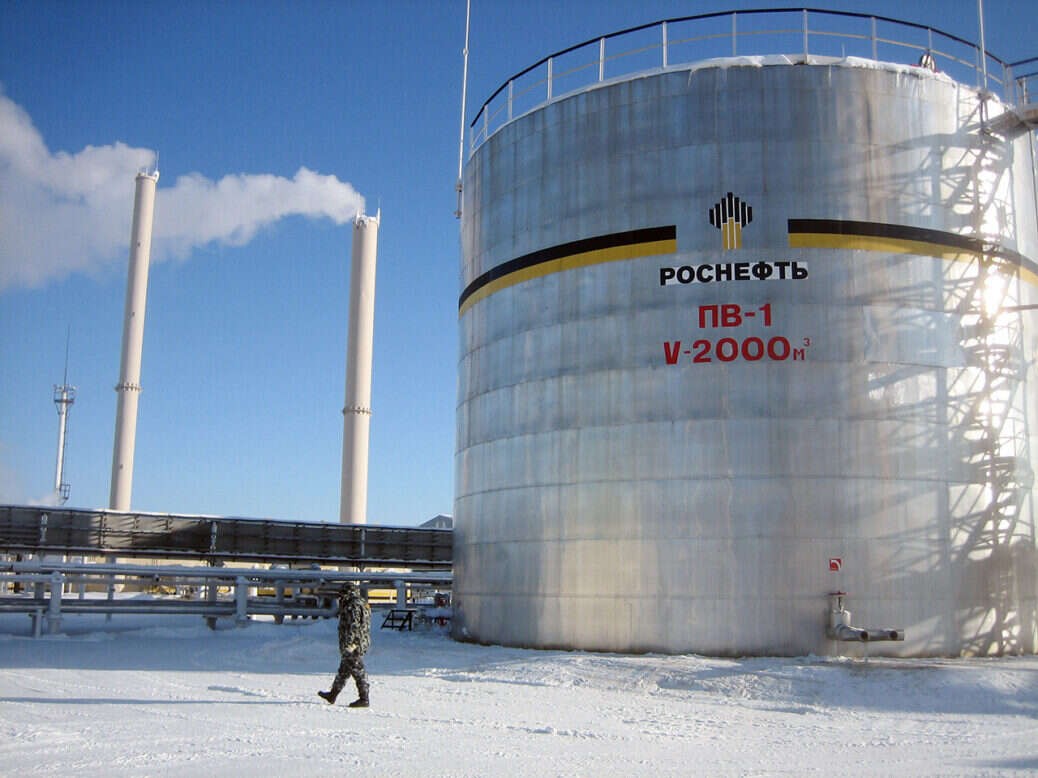

BP’s reaction to the Russian invasion of Ukraine was swift and substantive. In February 2022, just three days after the invasion, BP announced its intention to dispose of its 19.75 per cent stake in Rosneft, the Russian state-owned oil producer. That decision was widely praised because BP’s stake in Rosneft was worth $14bn, and it accounted for about 33 per cent of the oil produced by BP. However, sceptics also pointed out that it might struggle to sell the stake – after all, who but the Russian state would want to take it off BP’s hands? This turned out to be accurate: almost a year later the company’s chief executive, Bernard Looney, has told analysts that it is still “actively engaged” in marketing the stake.

While BP continues to try to sell its Russian asset, it continues to generate profits. Where is that money going? In the company’s statement today it said that “from the first quarter of 2022, BP has no longer reported oil and gas production from Russia”, pushing its total production down by 40 per cent compared with 2019. But Rosneft is doing well: its most recent results show its net income rose 13.1 per cent to 432bn roubles (£5bn) in the first half of 2022, with shareholders (“including BP”, Rosneft pointedly remarked) receiving over 441bn roubles in dividends. That money has to go somewhere. If not onto BP’s balance sheet, then where?

In a December update on its plans to exit Russia, BP announced that it written off $24bn following its decision, and insisted that it had “not received any dividends from the Rosneft shares”. It added: “It is our understanding that, under Russian regulations, any payments to a company in an ‘unfriendly state’ such as the UK would go into a highly restricted Russian bank account from which money could not be transferred without Russian government approval.” This followed an update in September, in which BP had said that it was owed dividends worth about 49bn roubles but that it had “not been formally notified of any such payment being made”.

Even if BP wanted the cash, sanctions on both sides would make it difficult to access. “Russia has imposed restrictions on the payments of dividends to certain foreign shareholders, including those based in the UK, requiring such dividends to be paid in roubles into restricted bank accounts and a requirement for approval of the Russian government for transfers from any such bank accounts out of Russia,” the company said.

If BP itself knows where the “highly restricted Russian bank account” is held, it’s not saying. But in theory, assuming the company is never able to dispose of its Rosneft stake, BP could have a tidy sum of money waiting for it when the war is over.

This may be unlikely, however, because – as the hedge fund manager turned campaigner Bill Browder has described – Vladimir Putin has a habit of helping himself to Western companies’ profits. “Given the extent to which Russia’s finances are increasingly against the wall due to sanctions, I am quite certain that the Kremlin would feel fully justified in taking the funds that have been left or waived by BP,” says Tom Keatinge, director of the Royal United Service Institute’s Centre for Financial Crime and Security Studies.

Oliver Bullough, author of Butler to the World: How Britain Became the Servant of Tycoons, Tax Dodgers, Kleptocrats and Criminals, agrees. “Russian court decisions have a habit of going the government’s way, around 100 per cent of the time, so I would imagine that as and when the Kremlin decides it wants the money, the Kremlin will help itself to it.”

Perhaps, with the benefit of hindsight, it might have been a more prudent decision for BP to keep hold of its Rosneft stake and deploy its profits to anti-Putin ends. “It would be better for BP to take the dividend and then donate that to a Ukraine reconstruction fund,” says Keatinge. “Then the money would be put to good use rather than either no use, or worse, handed to the Russian state to fund the war.”

Browder agrees: “At some point, Putin is gonna help himself to everything from the West. He will re-nationalise everything, because why should any private property be held when he can take it himself. In the meantime, they should look for ways of getting that money to the Ukrainians. They should allocate it towards refugees and aid to victims of the war in Ukraine.”

[See also: Why the West underestimated Ukraine]