What gender is Isla Bryson, formerly Adam Graham? According to the BBC and other media outlets, she is a she. According to the Scottish Conservative leader Douglas Ross, he is a he. Is a double rapist, who only began the gender reassignment process after being charged with the crimes, entitled to pronoun politeness?

For many, it is a confusing world we have entered as society seeks to better accommodate and support those with genuine gender dysphoria, but it has been made all the more confusing by the Scottish government’s approach to the issue. Nicola Sturgeon’s dismissal of the concerns of feminist campaigners – they were “not valid”, she said – has real-world consequences beyond the immediate impact of her Gender Recognition Reform Bill. I know of parents who are unimpressed, to put it lightly, that their 13-year-old children were recently asked, one by one by their teacher as they entered the classroom, which pronoun they wished to be addressed by that day.

Bryson has come along at entirely the wrong time for Sturgeon. It is practically the perfect case study in how male predators might use the new gender recognition laws to more easily self-identify as female, thereby seeking access to what should be spaces reserved for vulnerable women. I doubt the bone china was safe when news of Bryson’s rape conviction on 24 January, followed by incarceration in Cornton Vale women’s prison, reached the First Minister’s Bute House residence.

The prisoner’s estranged wife, Shonna Graham, has said that at no point during their marriage “did he say anything to me about feeling he was in the wrong body or anything”, although Bryson insists this has been the case since the age of four. Graham, who told the Daily Mail her husband was abusive during their marriage, is unconvinced. “He’s just bulls****ing the authorities,” she said.

In a sense, this case does Scotland a favour. The Gender Recognition Reform Bill, if it is allowed to come into effect, having been blocked by the Westminster government for fear it would affect UK-wide equality laws, would make it more straightforward for individuals to legally transition. They would only need to live in the gender they are transitioning to for six months rather than the present two years, and would no longer require a doctor’s diagnosis of gender dysphoria. The removal of the medical safeguard in favour of self-identification abandons any serious element of official external judgement as to whether the applicant is sincere.

Sturgeon and her supporters have insisted that the likelihood of men with malign intentions seeking to exploit this liberalisation is vanishingly small. Bryson has at the very least raised doubts about this argument and perhaps even exploded it. We don’t know whether this is a case of genuine gender dysphoria, or an attempt to avoid the harsh privations of a men’s prison, or an effort to gain access to potential victims in a women’s prison. But the general view, especially given the timing of the attempted transition, is that this person should be nowhere near a women’s prison.

Bryson has been moved following the public outcry of the past few days to a male wing of HMP Edinburgh, and Sturgeon is reported to be considering a directive to make sure no more rapists are sent to women’s prisons. But these issues were raised during the Holyrood debate before the Gender Recognition Reform Bill was passed in December; an amendment proposed by the Tory MSP Russell Findlay that would have meant a separate process for convicted sex offenders seeking to change their gender was voted down. Sturgeon seems to have been so intent on getting her changes through that she was unwilling to properly consider reasonable opposition arguments. The “not valid” quote has come back to haunt her, and I suspect not for the last time.

The case has also turned attention back to where it should be: on the legislation as it would affect Scottish society. Given how unpopular the changes are among the public, it was a matter of some joy to the SNP that the UK government blocked royal assent for the law. The weight of legal opinion seems to support that decision by Alister Jack, the Scottish Secretary, though the courts will ultimately decide. But it gave the Nats an out: this was now an issue about democracy and the independence of Holyrood, about arrogant, anti-devolution Tories at Westminster riding roughshod over Scotland’s parliament – it only confirmed the need for independence (though what doesn’t, in their eyes?).

But the truth is that Jack’s intervention has produced a timely pause, and one that seems to be allowing the national debate over trans rights, which Sturgeon had tried to avoid, to take place. The Bryson case has illustrated all too well how the legislation’s loopholes and lack of safeguards might be exploited, that it’s not beyond predatory men to seek to do so, and that women will, as usual, be their victims.

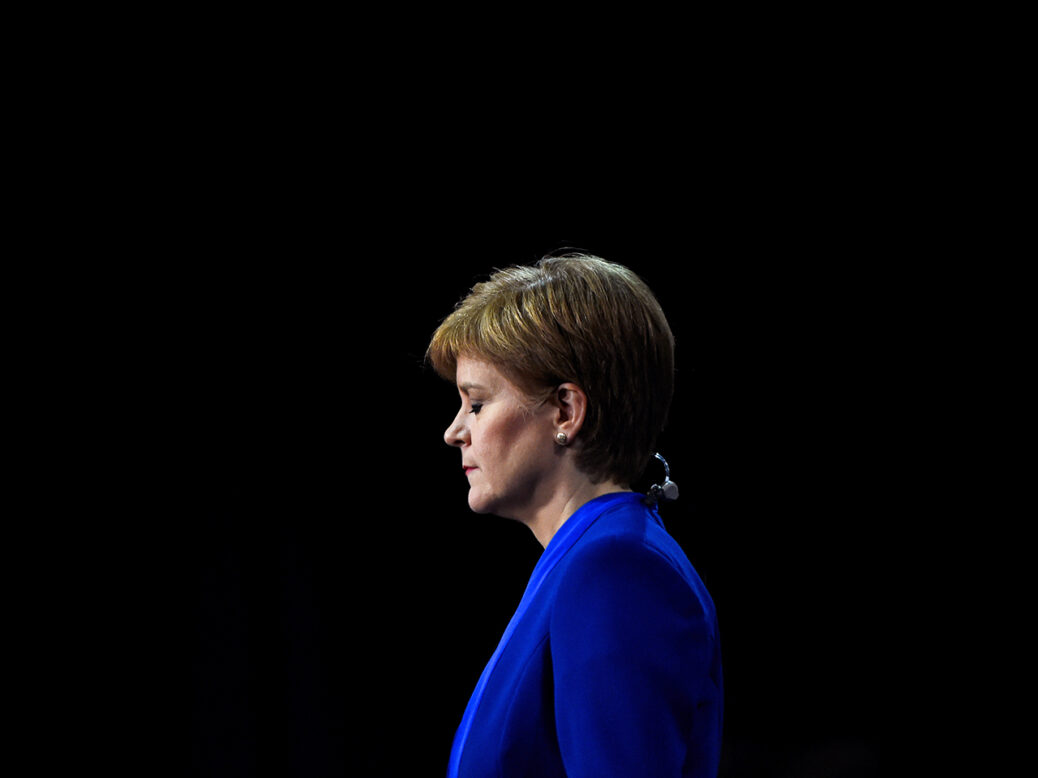

Sturgeon looked rattled at First Minister’s Questions yesterday (26 January) as she tried to deal with the fallout. If she had hoped this was now mainly a constitutional issue, the focus is firmly back on the rights and wrongs of the ill-considered laws she and her allies in Scottish Labour, the Lib Dems and the Greens are attempting to drive through. And if she had hoped that reality and time would show Scotland’s women that they had nothing to fear, she was very, very wrong indeed.

[See also: The tragedy of Nicola Sturgeon]