Late in the evening on 5 April, five days into Shanghai’s citywide lockdown, the residents of one housing compound began shouting from their windows that they were running out of food and basic necessities. As someone filmed on a mobile phone, a drone appeared in the night sky above them. “Please comply with Covid restrictions,” a woman’s voice announced from a speaker, as a light blinked on and off. “Control your soul’s desire for freedom.”

The footage was posted on the Chinese social media platform Weibo, and while it has not been independently verified, it has been widely shared as evidence of the city’s dystopian Covid controls.

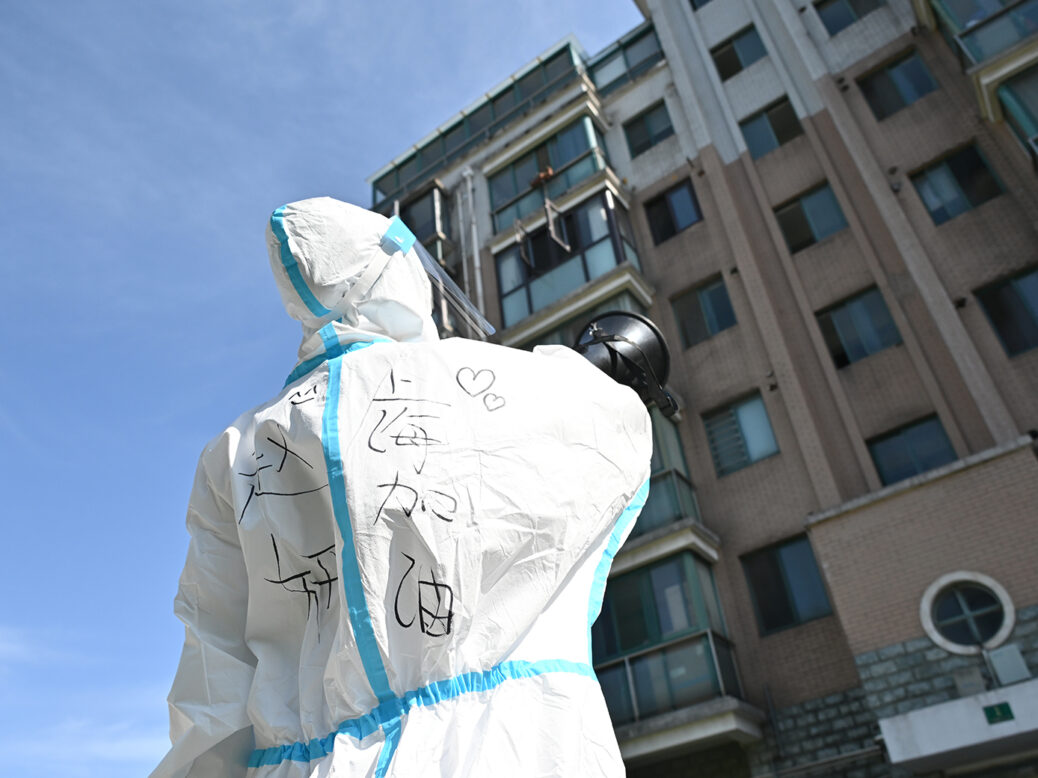

Half of the city was placed in lockdown on 28 March. The restrictions were extended across the whole of Shanghai on 1 April as the authorities struggled to contain a fast-spreading coronavirus outbreak. Close to 26 million people are now confined to their homes, allowed to leave only for essential reasons, such as to get tested for the virus or to pick up groceries. Yet even that has become difficult as supermarket shelves are emptied, and the food delivery services many people rely on are understaffed and overwhelmed. “The situation is extremely grim,” said Gu Honghui, director of Shanghai’s working group on epidemic control, on 5 April.

It is the sheer inhumanity of some of the official measures that has attracted the most anger, such as the policy of separating children from their parents if they test positive for the virus. Photographs and videos showing babies and toddlers sobbing at infant quarantine sites caused an outcry, forcing the local authorities to ease some of the restrictions. On 6 April city officials announced that parents who also tested positive would be allowed to accompany their children to isolation centres, and the families of children with special needs could apply for permission to stay with them regardless of their own status.

[See also: Did the UK perform better than we thought on Covid-19?]

As with the lockdown measures that were imposed in Xi’an in December, several people in Shanghai are said to have died after being unable to get urgent medical help because of the restrictions. The family of a nurse said they drove her to the accident and emergency department of the hospital where she worked after she suffered an acute asthma attack, but it was closed for disinfection and by the time they could get her to another hospital she was dead. Another woman died after being prevented from leaving her apartment block to receive her dialysis treatment, according to Human Rights Watch.

There has also been widespread revulsion after footage emerged on 6 April appearing to show a pet corgi being beaten to death by a public health worker on a Shanghai street. The dog’s owner later said they had been told to report for quarantine after testing positive for Covid and had decided to leave their dog outside, where they hoped the community would take care of it, fearing that it would starve if they left it locked inside their apartment. A state-run media outlet reported that the worker had killed the dog because they were “afraid of being infected”.

“I think there has definitely been a shift in the tone of the conversation online,” said Manya Koetse, the founder and editor in chief of the What’s on Weibo news site, which monitors social media trends in China. She noted that there had previously been high levels of public support for the government’s “zero-Covid”, or “dynamic zero” strategy, which aims to keep cases as close to zero as possible by imposing strict lockdowns and mass testing when a local outbreak is detected. There were signs that was beginning to change, however, at least with respect to local officials. “By early April the stress of the lockdown was really starting to take its toll,” Koetse explained, “and that’s when you saw people on social media asking for help and panic erupting.”

For much of the past two years, the Chinese government’s zero-Covid strategy has succeeded in limiting the spread of the virus. Case numbers have been a fraction of those seen in the United States and many European countries. Xi Jinping, the president, has held up the country’s handling of the pandemic as evidence of the superiority of its one-party political system. But with infections now surging and Chinese vaccines proving ineffective at preventing the spread of the highly transmissible Omicron variant (although they do still provide good protection against serious illness), tens of millions of people have been confined to their homes as mass lockdowns and testing remain the primary tools for controlling outbreaks.

“Many people joke that it’s not 2022, but 2020 too,” Koetse said. “They are asking how, after two years, does a city such as Shanghai not have a proper strategy to manage a lockdown, and to take care of people and their children, and their pets?” However, she stressed that, for now, that criticism was focused on the local authorities rather than the national leadership, which the censors would be much less likely to tolerate. “I think there are still many people who do trust the national strategy. They are just critical of how the local authorities are implementing it.”

Beyond the immediate outbreak in Shanghai, where case numbers are still rising and there is no end to lockdown in sight, the larger problem for the Chinese government is how to move towards a more sustainable model of living with the virus in the longer term. Without a more effective vaccine, and with many elderly citizens not vaccinated at all, the authorities fear a crisis that would overwhelm the country’s healthcare system if they move away from their zero-Covid approach. If they don’t, however, the mass lockdowns, shortages and suffering will go on.

[See also: China’s zero-Covid policy faces its greatest test]