On a Sunday afternoon in mid-February, Michael Sheen and Tony Blair laughed when they first saw one another on Zoom. They are two very different national figures, but their careers are nevertheless entwined, the actor having played the former prime minister three times – most notably opposite Helen Mirren’s Elizabeth II in the 2006 biopic The Queen.

Sheen no longer looked eerily like Blair. Dialling in from Glasgow, where he was filming a new series of Neil Gaiman’s Good Omens, his thick curls had been replaced by a short shock of peroxide blond. Blair, in turn, had cut the long hair he grew during the pandemic, described in the British press as his “lockdown mullet”.

“You look younger,” Blair said. “My lockdown hairstyle was much commented on –but not that I looked younger.”

They had met to talk about the meaning of Britain, which has changed greatly since Blair left office in 2007, and since Sheen last played him in the 2010 television film The Special Relationship (opposite Dennis Quaid as Bill Clinton). During the tumultuous decade since its release, a succession of Conservative-led governments have shrunk the state after the largesse and renewal of the New Labour years. The UK has left the European Union, its identity now split between Little Englander neurosis and Global Britain fantasy – a messy rejection of the globalisation synonymous with Blairism. With the creation of an Irish Sea border, and a Brexit-sceptic Scotland, the Union itself is under threat.

Speaking a week before Russia invaded Ukraine, the two men discussed what a “British Dream” should be, the future of the Labour Party, and the UK’s changing role in the world – questions that have become more urgent since the outbreak of war.

Representing different traditions of the left, Sheen and Blair clashed over what went wrong for Jeremy Corbyn and how Labour can win again, but agreed on one fundamental challenge: watching oneself on screen.

Introduced and chaired by Anoosh Chakelian, the NS Britain editor

Michael Sheen I have a lot of cognitive dissonance when it comes to you, because it’s like seeing a family member or something. I remember Stephen Frears, who directed two of the films where I played you, said “Don’t ever forget that these are the smartest people in the room, always.”

Tony Blair That was generous, if inaccurate.

MS When we were making The Queen, it seemed as if [by the time of New Labour] the story Britain told about itself had changed. The Britain you grew up in, were educated in, became a barrister in, got into politics in – what was that Britain telling the world about who it was, and why did you come to think that story needed to change?

TB Britain finds it very difficult to tell a story about itself, because there is a narrative that supposes our best days are behind us, and that’s caught up in what happened in the Second World War: Churchill defeated Nazism, Britain’s finest hour.

My idea was to take what I think are the enduring best qualities of Britain – open-mindedness, tolerance, innovation – and try to give Britain a different narrative that would allow it to think its best days are ahead of it. I think, for a time, that succeeded, and it probably culminated in winning the Olympic bid in 2005. We quite deliberately put Britain forward as a multicultural, tolerant society, looking to the future, and I think that’s why we won that bid. And then the Olympics, when it came about in 2012, was in many ways a celebration of that.

But there have always been these two competing ideas and, bluntly, I think that over the past few years, the older narrative has reasserted itself. You only have a concept like the American Dream – and Xi Jinping now talks about a Chinese Dream – when you think your best days are ahead of you.

MS After the war, with that 1945 government and the huge changes made to the country, when did people start looking back?

TB At the end of the 19th century, we were the most powerful country in the world. The Second World War demonstrated the capacity of Britain still to play a leading role on the world stage. But from then on, you were relinquishing the trappings of empire and power.

People on the left will baulk at what I’m about to say, but in some ways, with Margaret Thatcher, there was at least the strong direction recovered. And then with New Labour, that was a progressive attempt to say: we’ve got a strong relationship with Europe, we’ve got a strong alliance with America, we’re globally significant, we’re modernising our country, we can become a centre of innovation, technology for the future. It’s still possible for us to do all of that, but in the past few years there has been something of a crisis of identity for the country.

MS How much did that weigh on you as prime minister, the country having once been the most powerful force in the world, and holding on to that influence?

TB It weighs on you for two reasons: first because of the richness of your history, but also because if countries today want to succeed, they need direction. One of the biggest problems we have right now in Britain is we don’t have a plan for our future. We’ve got three revolutions – Brexit, climate and technology – and we’re not really planning for any of them.

Countries need a sense of direction, and they need to find their place in the world. What is the role of Britain today? This is something that you have to define, some sense of the dream of the future, because that means nothing unless it’s definable.

I think you could have a British Dream, but it requires you to understand what you can offer the world today. And I think it is about being an open-minded, tolerant, innovative country and society, because that’s where we, throughout our history, have always been when we’re at our best.

Britain’s place in the world

MS Britain’s relationship with the US and Europe has changed since you were in power. How does that affect British influence? Part of going into Iraq was to stand with America.

TB We don’t have those two relationships in the same way, and as a result, we’re less influential. It’s clear. In my time, and under John Major, Margaret Thatcher, Gordon Brown, the first recipient of a call from the president of the United States would have been the British prime minister. I’m not sure that’s really true any more.

The relationship with America comes at a price, the relationship with Europe comes at a price. I never pretended that the European Union was perfect or that it was always easy-going. It wasn’t. It was very hard a lot of the time. But the relationship mattered to how we looked at ourselves and our place in the world and our ability to influence things, and therefore, when you undermine that in such a fundamental way, it’s difficult.

You can’t escape these choices. If you’re constantly indulging the view that there is a past you can recapture – which is an easy thing to do, a very simple populist message that may be politically successful in certain contexts – it doesn’t offer anything for the future.

MS It seems a large part of why people voted to break away from Europe, was out of some sense of wanting to go back to the past, of Britain as this buccaneering spirit, and an empire-building attitude. And yet it seems to have given up influence by leaving the EU. There’s a bizarre irony in that, isn’t there?

TB Yes. You’re in a much stronger position to deal with these countries whose economies eventually will be far larger than ours – China’s already is, India’s in time will be – from a position of partnership.

In the world that’s developing today, you’ve got three giants by the middle of this century: America and China for sure, and probably India. These will be giants taller than any other country; and then you’ll have the tall countries, populations like Indonesia, Brazil and Mexico and so on. France, Germany, Italy, Britain will all have populations of roughly 65 or 70 million. Unless you band together, you’re just going to get sat on by the giants.

The belief in better

MS The idea of aspiration was key to the New Labour vision for Britain. Why do you feel your record on social mobility has been misrepresented by the left?

TB Simply because when you look at the opportunities we gave people, they were immense: university education was expanded, Sure Start, massive investment in schools, big inner-city regeneration. When we left office, the NHS had its highest satisfaction ratings since records began.

It’s important for the left not to misrepresent the last Labour government, or play along with the idea that it was all about Iraq and nothing else, because then all you do is depress people about future prospects.

MS There is the idea that your government was the most redistributive since 1945, and that it was happening by stealth. But there was a tension between staying attractive to the kind of voters you need to get into power and trying to do what a Labour government is there to do, which is to be the party of social justice and a fairer economy. How did you cope with that tension?

TB That was, and is, the challenge. Provided it was clear Labour was in favour of successful business, happy for people to be ambitious and do well, strong on defence and law and order – because people care about those things – then, as it were, you got permission to do the side of it that was about social justice and compassion and liberal change.

I could see there was a new coalition emerging of people who were pro-free enterprise. In that sense, they had sympathy with the Thatcher concept, but at the same time they were socially liberal: they’d no time for racism or discrimination against gay people.

The working class – in the traditional sense that Labour often uses the word – had always had two bits to it, and one was fiercely aspirational. And that fiercely aspirational part was always what the Tories appealed to. My father was one of those people: brought up in a poor part of Glasgow, secretary of the Young Communists, and then later became convinced that Labour wanted to hold him back, and he wanted to succeed.

That is the great challenge always of progressive parties. But it’s not a challenge you can’t overcome, and Labour could do the same again today, if it decides to.

MS At a party conference fairly early on in your government, you said the fight was for a new vision of a Britain in which the old conflict between prosperity and social justice is banished to the history books where it belongs. Do you think it’s possible for a party that openly advocates social justice and a fairer economy to win power in a period where this is labelled as “wokeness” and smeared as something else? Some people say you were so successful electorally by fooling Britain into thinking that it wasn’t the Labour Party! Could someone openly just say, “This is what we believe in”? Is it possible for this country to vote that someone into power, and if not, what does that say about who we are?

TB You’re remembering my speeches better than I do! You can definitely say we want social justice and a fairer country, provided people think you’ve got a plan that’s sensible to get there. There’s no purpose in the Labour Party if it’s not going to create a fairer society and implement measures of social justice. The question is how.

What Labour people often tend to do is misunderstand why people are voting Tory. They’re often voting Tory because they fear Labour – not because they fear Labour is going to create a more just society, but because they fear Labour will bind them up in a whole lot of state power that won’t necessarily deliver that just society.

People say to me, “Labour got hammered at the last election.” And I say to them – I don’t mean to be rude about it – but we put forward Jeremy Corbyn as the prime minister – what do you think’s going to happen? What is it about British political history that tells you they’re going to put someone from that political position in charge of the country? Nothing!

Labour doesn’t need to apologise for wanting a more just society. On the contrary, it needs to say that this is its mission. It’s how you do that in the modern world that always trips up Labour. If you go back to the 1945 government, which created these great changes, the question is: why were they voted out in 1951? It happened because the Tories were able to argue Labour wasn’t paying attention to the aspirational side of the working-class people who were being helped by the very changes Labour was making.

If you want to achieve power, you’ve got to be much more intellectually rigorous about what your problem is. It isn’t that people think, “I can’t vote for people who want a more just society.” They’re not voting Labour because they worry that what we might do isn’t in line with what they conceive a more just society to be. Those two things are reconcilable, but only if you’re hard-headed about what the problem is.

MS I’m concerned that unions and collective action are now seen as regressive, and people I know don’t have any protections – people who come from the area I come from [Port Talbot in Wales] and who I meet every day. Part of the attraction for a lot of people of Jeremy Corbyn – even though his leadership was seen as “going back to the Seventies” – is that people need protection at work, when they’re on a zero-hours contract or working in an Amazon warehouse.

TB You’re absolutely right, that is the need. There are a lot of people who are exploited in the workplace today. You need trade unions that are forward-looking, that understand what the realities of the world are, how you best get that protection. They probably aren’t trying to play around with the politics inside the Labour Party, to be quite frank, but addressing the workplace issues that people have in a very practical way.

People used to think I was always rebuffing the trade unions. I used to try to explain that, if you want to represent the modern workforce, you’ve got to go to where they are and how they think, and be directed towards genuine workplace representation – not try to pull them into what they think ends up as a sort of quasi-political organisation.

We introduced the minimum wage. We introduced the right to be a member of a trade union. We got rid of a whole raft of Tory things that were anti-union. But what we didn’t do was everything the trade union movement was asking, which literally was to go back to the framework of the 1970s.

The psychology of the country towards the Tories and Labour is different. Towards the Tories, it’s: “I don’t particularly like them, I think they do look after the most wealthy in society. On the other hand, I know that all they’re interested in is power, and therefore, probably, they’ll try to work out what I want and try and give it to me.”

With Labour, it’s completely different. It’s only Labour that worries about whether it’s principled: the country thinks the party is principled. What the country worries about is: “Labour definitely believes these principles, and Labour’s got a huge commitment to social justice, but what’s that going to cost, exactly? Can you actually run the thing or will these principles be so important that you’ll take us in all sorts of strange directions?”

MS I’m not so sure that people do think that about Labour. Part of the toxicity of the whole system is that people now – and maybe this is why the fallout is worse for Labour – are seen as being hypocritical. Anyone who stands up and says, “I’m doing something good” or, “I’m doing something for others” gets criticised for being hypocritical, and everyone looks for reasons why they’re just out for themselves.

TB I don’t know whether that’s very new, though.

Shifting party lines

MS The concept of right and left is clearly shifting: the idea of the Red Wall, and traditional working-class voters moving towards the right, the idea of culture wars and identity politics mixing it all up. Do you still think the concepts of right and left are valid, and how does Labour deal with that shift?

TB Of course I believe there’s still a right and left. There’s still a basic conservative position and a basic progressive position, and there always will be. All that’s happened is that the traditional loyalties of people to a traditional Conservative Party, a traditional Labour Party or progressive politics, have eroded.

I think, Michael, you’re searching for a complicated explanation of why Labour’s been losing, whereas I think it’s not that complicated! If you look at the culture wars, identity politics, it’s exactly the same as the 1980s. If Labour gets in the wrong place on these things, it’ll alienate part of the working-class vote, a part of which is small-c conservative. If you look as if, on identity politics or culture, you are far away from those people, you’ll frighten them: they won’t vote for you. That’s why one of the first changes I made when I was shadow home secretary was to make Labour the party of law and order, because crime is worst in the poorest communities.

Remember the Tories in the 1980s and early 1990s were thunderously anti-gay rights. But I was very confident we could hold that ground, provided that on issues like law and order we were strong. Because in the end, my instinct is that most British people actually think: “Live and let live and it’s up to you how you live your life, that’s your decision.” Whereas on law and order, they think: “No, I want a government that’s going to look after my security, that I really care about.”

MS What’s known as identity politics and the culture wars is clearly something that the right loves to be able to paint the left into a corner on. Some would say it’s also a distraction used by the left: pushing for equality of representation actually distracts from the really deep, structural systemic changes that need to happen.

I suppose this touches on the idea of the centre. The centre can look pretty extreme, depending on where you come from. For certain people in the sort of communities I come from, the idea of the centre – even if it is dressed up as being very liberal and progressive and wanting equality of representation – is still potentially propping up an economic system that has left them behind. If you see that society needs structural change, how can you say the centre is the way to go?

TB Well, the centre should always be radical, but you should be against injustice, whatever form it takes. Injustice can take a structural or class form, but it can also take the form of prejudice based on your sex, gender or ethnicity. I don’t see this as an either/or. But I think you can be radical, provided you are radical in the right way.

These areas that are left behind, they require regeneration. When we were in government, a lot of our major cities became much more dynamic, regenerated. The biggest pockets of inequality today are in areas where there used to be a traditional industry that has now gone – and that’s been a problem stretching back over half a century. You need very specific policies to deal with that. Or they’re in towns that haven’t shared in the prosperity of the big cities.

The left has traditionally defined a radical solution as more state power, but I don’t think that’s the way the world works any more. That’s why you’re better looking at infrastructure, education systems, the way the benefits system is structured. How you look at ensuring that you’ve got centres of innovation and technology in some of the poorest parts. This is a problem in the US, France, Germany, everywhere. The answer is to have radical policies that are also relevant.

Keir Starmer and Labour’s future

Anoosh Chakelian What are your reflections on Keir Starmer’s leadership of Labour?

TB I think Keir’s doing a very good job. He’s shifting the party in the right direction and that’s why he’s getting a response from the public. But, you know, the Labour Party – I said it needed deconstruction and reconstruction, and I still think that’s true. And I think Keir is embarking on that.

MS You have said that, “Without total change, Labour will die.” If it’s change or die, is he changing Labour enough?

TB Keir is changing it, but it will require a lot of change. Labour has been in existence for 120 years; it’s been in power for less than a third of that time, and the longest period in power by far was New Labour – and a large part of the Labour Party is not really comfortable with that bit.

If you look at Labour over 120 years, you can’t say it’s a successful political project, I’m afraid. You can say it’s a great political movement, but in electoral terms, it has not been as successful as it should have been. That’s clear. The question is why, and I think the answer is that the Liberal progressive and Labour progressive traditions got separated at birth. That’s been a problem for Labour all the way through. New Labour was an attempt to reunite those two traditions.

This is really important for Labour to understand, especially having just gone through the period of leadership that we have. Unless it’s very clear that we understand not just what our mission is, but what people expect from the Labour Party today, I think it’s tough. But Keir is moving it in the right direction; he’s taking a lot of brave decisions and I support him in doing it.

MS I think you have more in common with Jeremy Corbyn than Keir Starmer, because part of the appeal of New Labour is that it was a radical offer. How does Labour reclaim something that is radical and yet doesn’t smack of the past, which holds the values of the party?

TB This may surprise you, but I agree with you to this extent: that it is important you’ve got a radical offer. And I agree with you also that Corbyn did have a radical offer, and that did inspire a significant group of people. The trouble was, it was a radical offer that alienated a larger group of people called the electorate. This is why I’ve been saying to the Labour Party: what is the big real-world change that’s going on today? It’s the technology revolution. If people aren’t able to participate in it, that will be a huge new source of division in society: between those who get it, can handle this new world, find their place in it, and those who can’t.

The problem with the radical Corbyn offer is that, in default of anything coming from what I would call the radical centre, he at least seemed to offer big change, and people say, “I want big change.” The difficulty is, it’s the wrong type of change. You have to inspire people with the thought that it’s going to be radically different. That’s the policy challenge for Labour.

Divide Keir’s challenge into two parts: one is putting across that the Labour Party is reasonable, sensible, etc. But I agree with you: you’ve then got to put in place a policy programme and platform where people say, “Wow, I think that makes sense of the world to me, and how it’s going to change, and how I find my place in it.”

The disunited kingdom

MS Was the devolution done under your government an attempt to strengthen the Union? If so, do you think it has, and how can that sense of union be revivified?

TB One part of me thinks: by ensuring a Labour government is a realistic possibility. For some parts of Scotland and Wales, if people think they’ve got a Tory government forever, they despair and look for a different way out. We did devolution, yes, to strengthen the Union. If you look at the history, the pressure for change in the way Scotland was governed was either going to be met with devolution or independence. The status quo was not sustainable. People forget the independence movement of the 1960s and 1970s was very strong. The same arguments apply for keeping the UK together as keeping the European Union together. In the end, there is a level at which decisions should be taken locally, but there are certain things where you will leverage the power of the bigger unit.

We created the Scottish Parliament, the Welsh Assembly, the peace process in Northern Ireland delivered the Northern Ireland Assembly, we created the position of mayor of London. I didn’t feel the union was under threat in our time in government, but it came afterwards. It was bubbling up, and then there was the Scottish independence referendum in 2014, and independence was defeated.

But Brexit, frankly, has given a new lease of life to this, and there’s no way out of that. I worry most about Northern Ireland. I still think, ultimately, people in Scotland will feel their economic interests are with England, whereas what Brexit has done in Northern Ireland has significantly weakened the Union.

MS Can you envisage a future where an independent Scotland, an independent Wales, allow a new version of Britain to thrive?

TB I struggle. It is very similar to the Brexit thing. You can carry people along in a great tide of emotion, but when you look at the practicalities, they’re pretty severe. I think that’s why it won’t happen. It’s a perfectly reasonable debate, and you’ve got to have the debate, because the feelings are there. But I can’t envisage a situation in which Britain is stronger by no longer being Britain.

Blair on Blair

Anoosh Chakelian Michael, you’ve played Tony three times – how did you get into character? Tony, what did you make of his performances, if you’ve been able to bring yourself to watch them?

MS I’ve played a lot of real-life people. I take it on as a real responsibility: you’re dealing with someone’s actual life. People, rightly or wrongly, are going to look at what you do and believe that’s what happened.

I try to immerse myself in everything I can read and hear about the person, and to let it happen without any judgement. It’s like taking a warm bath in someone’s life. That’s not a particularly pleasant description, but taking a warm bath in Blair, and then letting whatever comes out come out, trying never to underestimate, or have an agenda. Never go for the simple answer, always look for the contradiction, the complication, the richer, more problematic side of the person.

Because people are complicated, it doesn’t matter who you are. But I can’t watch it. I did it three times and only by the third time could I even really watch it and go, “That’s not a caricature any more.”

TB It’s funny you say that, because let me be absolutely frank: I genuinely have never watched the performances all the way through. I’ve seen clips; my family have watched all of them and tell me about all the scenes. In the only bits I’ve seen, what does come across is that you’re actually representing a character and not a caricature, and that’s actually very powerful. You’re a brilliant actor. By all accounts, the portrayals are all very good, and from the short bits my kids have shown me, you do extremely well.

I never watch myself. I don’t watch anything about myself, because I know if I’m sitting there watching it, afterwards I’m going to be thinking, “Well, that could be different.” But it’s a very odd thing to see yourself portrayed on screen. When you become a prime minister, or even just a leading politician, it’s kind of a conspiracy against you being normal. And one of the things that reduces the normality is seeing yourself portrayed: it’s a slightly scary feeling.

Role reprisal

MS Gladstone was a few years older than you when he formed his second government – second of four, as you know…

TB Yeah, well, good for Gladstone! But no, I think the next Labour prime minister will be someone else, hopefully Keir.

MS But then Gladstone did do four, so he was 82 by the time he did his fourth.

TB Yeah, I know. Gladstone was an amazing man, and how he came back… But I think politics was a little different then.

MS Genuinely, you wouldn’t want to get back into that arena again?

TB Let’s say I don’t think that route would be open to me, even if I wanted it, so it’s not something I think about at all. But I’m very happy doing the work that I’m doing at the moment. I find that very fulfilling. It’s taken us a long time to build this organisation that we have now, the institute [the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change], and I think we can build it even bigger and that’s really my focus, to be honest.

What I would like to do is help on the policy side with the next Labour government, because I think you do put your finger on a very important point: it’s got to be a platform that makes people think the world’s going to change, it’s just got to be the sort of change they’re not frightened of.

MS I’ll keep my costume in the wardrobe.

TB Just in case!

This interview has been edited and condensed.

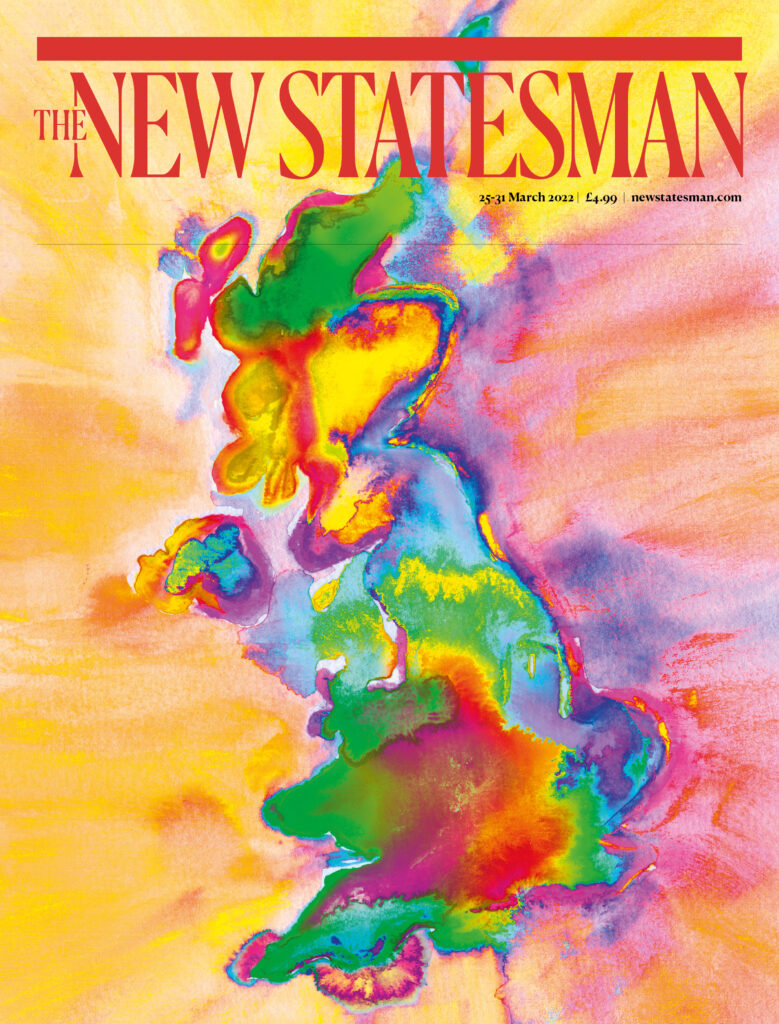

This piece is published in Michael Sheen’s guest edited issue of the New Statesman, “A Dream of Britain”, on sale from 25 March.

This is the second instalment in the New Statesman’s “Face to Face” series. The first was a conversation between John Gray and Ross Douthat.

[See also: David Miliband: “Only brilliant people win from the centre left”]

This article appears in the 23 Mar 2022 issue of the New Statesman, A Dream of Britain