It really isn’t a secret what Scotland thinks. Regardless of what the politicians tell them they should want, voters are remarkably consistent. In poll after poll, they give the same answers to the same questions.

What we know: support for independence is a little shy of 50 per cent; there is little desire for a referendum any time soon, other than among hardline nationalists, and even some of them entertain doubts; despite this, the electorate wants the SNP to remain in government and Nicola Sturgeon to remain as First Minister; there is intense dislike of Boris Johnson; neither of the two main Holyrood opposition parties yet looks like a government-in-waiting.

A fascinating poll in the Times this week adds some relish to the burger. It finds that a majority of voters believe support for independence should be registering at around 60 per cent for a year before a second referendum is called. They think the NHS should be Sturgeon’s priority – independence has slipped to eighth, and even a third of SNP supporters put it outside their top three issues.

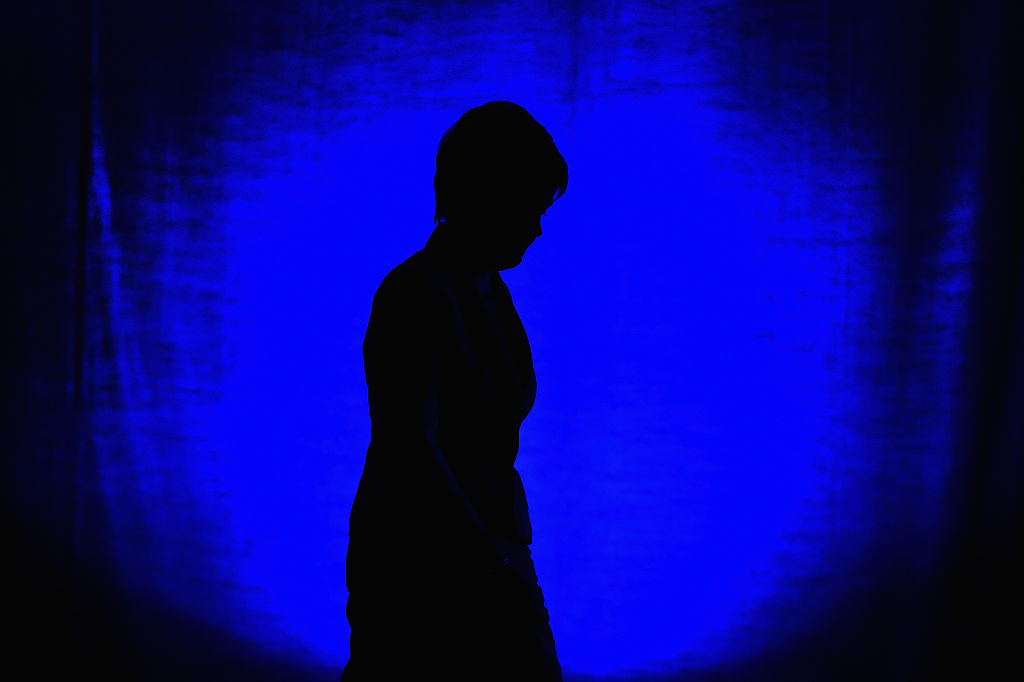

Given that the First Minister seems to have her heart set on a referendum by the end of 2023 – that, at least, is her public stance – the data suggests Sturgeon’s party is heading for a confrontation with the electorate that so recently returned it to government. This unrelenting focus on the constitution, and perhaps a more general fatigue with politics and politicians after a hugely proscriptive and interventionist period, appears to be taking its toll. Sturgeon’s popularity rating has fallen almost 40 points since August last year, when it was +50. Here, the only relief is that all of her rivals are still less popular.

If you are not a Scottish nationalist who only hangs around with other Scottish nationalists and who views everything through the prism of Scotland gaining its “freedom”, nothing in the polls will come as a surprise. Most people pay little attention to the daily ins and outs and ups and downs of politics. They have spent the past two years worrying not about what currency an independent Scotland would use or whether Westminster has exploited the Sewel convention, but about their children’s education, their elderly parents’ exposure to Covid, and whether they’ll have a job to go back to at the end of furlough. They are concerned by the mounting number of abandoned shops on their high streets, blanche at the tatty state of many streets, and are infuriated by cuts to the regularity of the local bin collection. They might nurse an intense dislike of the Prime Minister, in particular, but they have scant regard for the political class as a whole.

[See also: The SNP needs to stop blaming everyone but itself]

Amid all this, and with so many of our challenges remaining unaddressed, the independence debate can look like a game being played by an elite few, and one that is not especially relevant and certainly not urgent. This is what non-politicos tell me, and it’s what the polls say.

This is the cleft stick on which Sturgeon is caught. Her determination to hold a referendum by 2023 has been stated with enough regularity and conviction than anything short of that outcome will be an embarrassment, especially when it has long been obvious that the UK government will refuse permission. Yes supporters will rightly feel taken for fools, having had to embrace a fairly acrobatic piece of cognitive dissonance – there both will be a referendum and there won’t; they must prepare for the brutal intensity of a campaign that won’t happen; they must march and boast and goad knowing that they will probably be left empty-handed.

These contradictions have left observers wondering just how long Sturgeon can go on. Her public utterances about fostering children and life after Bute House, and her hyperactivity at Cop26 were taken as a hint that she is looking beyond her current office to a more normal family life and, say, a job with the UN. She denies she is planning any such thing in the near future, and insists she will see out her term as First Minister, which runs until 2026.

If, by then, there still hasn’t been a second vote on independence, it’s clear the SNP will face something of an existential crisis, having been in power for nearly 20 years and with its ultimate goal no closer to being achieved. The end of a cycle, of a way of thinking, will have been reached and what follows will have to be different. There will be a choice to be made.

Does the party opt for a successor in the Alex Salmond mould, attempting to bully, cajole and harass Scots towards independence? Or does it choose someone like economy secretary Kate Forbes, a technocratic intellectual who might try to govern devolved Scotland with greater ambition than the conservative Sturgeon, embracing a higher degree of policy risk and perhaps with a stronger focus on economic growth – all with a view to convincing voters that even more could be achieved with independence. And which would be more successful?

That, at least, is something we don’t yet know. But one way or another, the end of an era is in sight.

[See also: The tragic failures of Scottish devolution]